U.S. doctors plan to treat cancer patients using CRISPR

The first human test in the U.S. involving the gene-editing tool CRISPR could begin at any time and will employ the DNA cutting technique in a bid to battle deadly cancers.

Doctors at the University of Pennsylvania say they will use CRISPR to modify human immune cells so that they become expert cancer killers, according to plans posted this week to a directory of ongoing clinical trials.

The study will enroll up to 18 patients fighting three different types of cancer—multiple myeloma, sarcoma, and melanoma—in what could become the first medical use of CRISPR outside China, where similar studies have been under way.

An advisory group to the National Institutes of Health initially gave a green light to the Penn researchers in June 2016 (see “First Human Test of CRISPR Proposed”), but until now it was not known whether the trial would proceed.

"We are in the final steps of preparing for the trial, but cannot provide a specific projected start date,” a spokesperson for Penn Medicine told MIT Technology Review.

The Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, a charity set up by billionaire entrepreneur Sean Parker, one of the founders of the music-sharing site Napster, confirmed it is helping to finance the study.

The CRISPR trial, led by doctor Edward Stadtmauer, involves reprogramming a person’s immune cells to find and attack tumors.

To help enhance the treatment, Penn scientists intend to use CRISPR to delete two genes in patients’ T cells to make them better cancer fighters. One of the genes to be removed makes a “checkpoint” molecule, PD-1, that cancer cells exploit to put brakes on the immune system.

A further edit will delete the receptor that immune cells normally use to sense danger, like germs or sick tissue. An engineered receptor, added in its place, will instead steer them toward particular tumors.

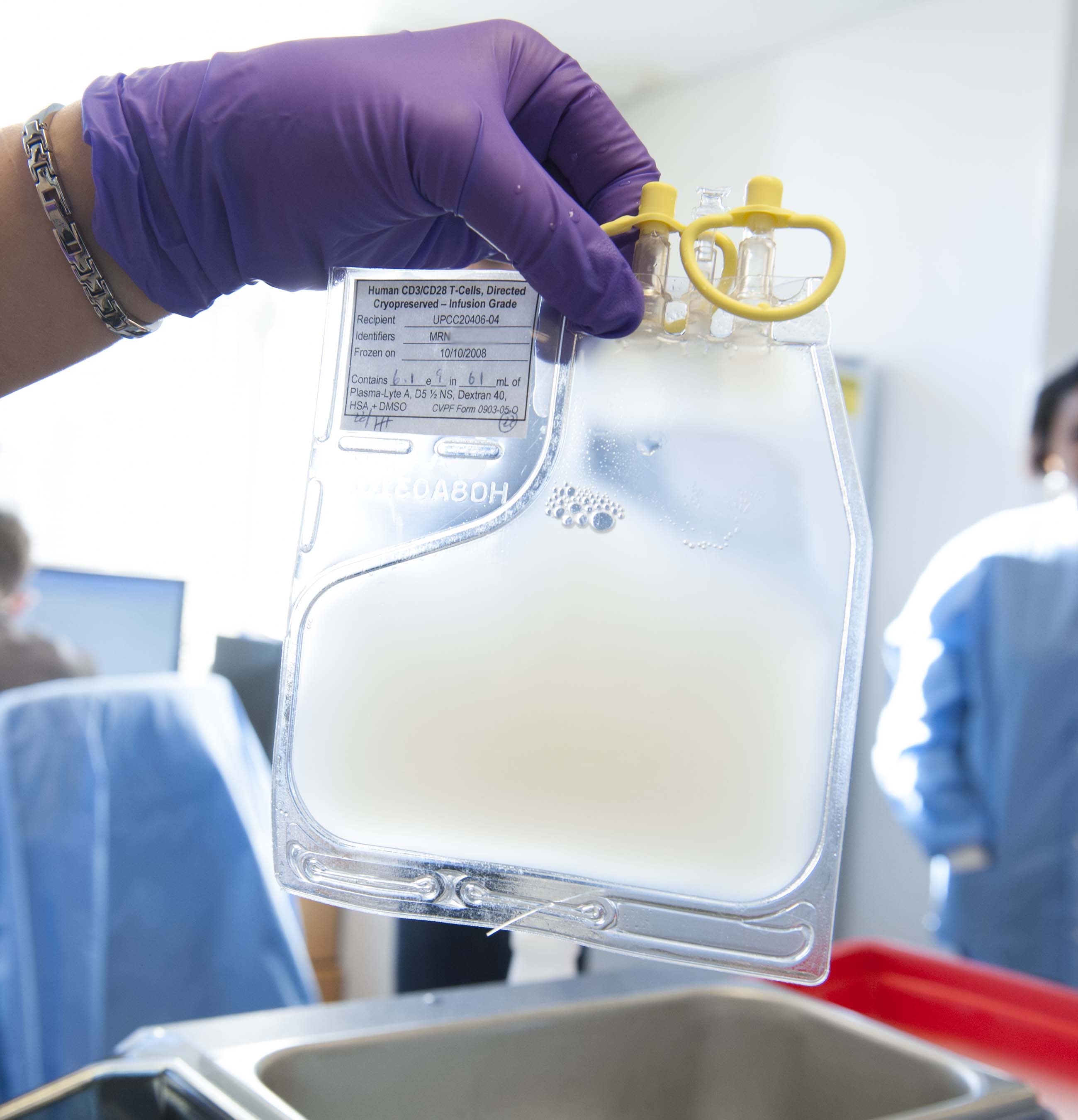

In the study, doctors will remove people’s blood cells, modify them with CRISPR in the lab, and then infuse them back into the patients.

This outside-the-body approach, called ex vivo gene therapy, is considered less risky than injecting CRISPR directly into a person’s bloodstream, which could cause immune reactions.

A second CRISPR trial that could begin in Europe later this year will also pursue the ex vivo approach. CRISPR Therapeutics, a biotech company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, asked European regulatory authorities in December for permission to try to cure beta thalassemia, a blood disorder, by making a genetic tweak to people’s blood cells.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.