A coronavirus vaccine will take at least 18 months—if it works at all

This story is part of our ongoing coverage of the coronavirus/Covid-19 outbreak. You can also sign up to our dedicated newsletter.

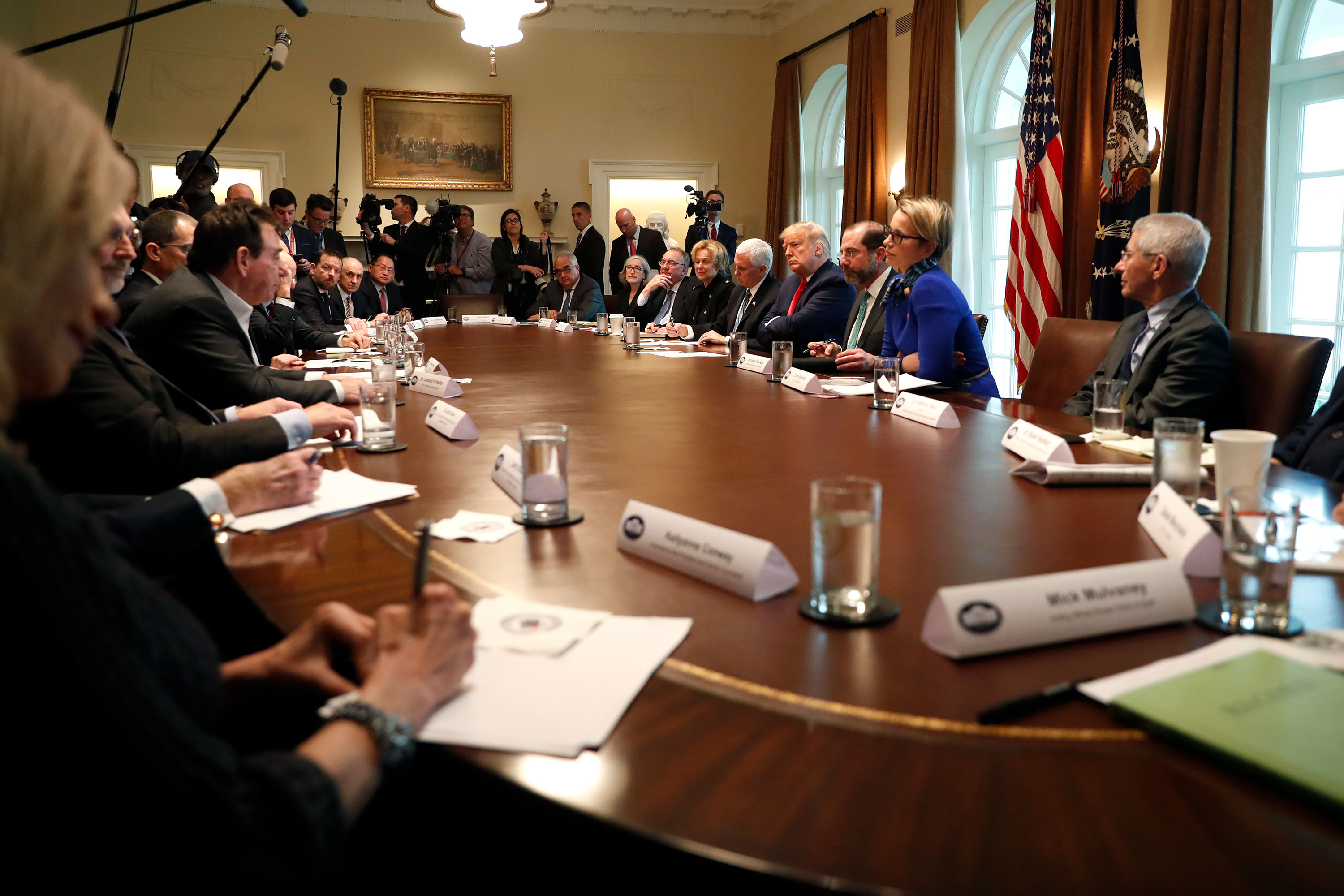

During a press opportunity on March 2, a dozen biotech company executives joined President Donald Trump around the same wooden table where his cabinet meets.

As each took a turn saying what they could add to the fight against the spreading coronavirus, Trump was interested in knowing exactly how soon a countermeasure might be ready.

But only one presenter—Stéphane Bancel, the CEO of Moderna Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, Massachusetts—could say that just weeks into the outbreak his company had already delivered a candidate vaccine into the hands of the government for testing.

“So you are talking over the next few months you think you could have a vaccine?” Trump said, looking impressed.

“Correct,” said Bancel, whose company is pioneering a new type of gene-based vaccine. It had been, he said, just a matter of “a few phone calls” with the right people.

Drugs advance through stages: first safety testing, then wider tests of efficacy. Bancel said he meant that a Phase 2 test, an early round of efficacy testing, might begin by summer. But it was not clear if Trump heard it the same way.

“You wouldn’t have a vaccine. You would have a vaccine to go into testing,” interjected Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease, who has advised six presidents, starting with Ronald Reagan during the HIV epidemic.

“How long would that take?” Trump wanted to know.

“Like I have been telling you, a year to a year-and-a-half,” Fauci said. Trump said he liked the sound of two months a lot better.

The White House coronavirus event showed how biotech and drug companies have jumped in to meet the contagion threat using speedy new technology. Also present were representatives of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, CureVac, and Inovio Pharmaceuticals, which tested a gene vaccine against Zika and says a safety study of its own candidate coronavirus could begin in April.

But lost in the hype over the fast new vaccines is the reality that technologies such as the one being developed by Moderna are still unproven. No one, in fact, knows whether they will work.

Moderna makes “mRNA vaccines”—basically, it embeds the genetic instructions for a component of a virus into a nanoparticle, which can then be injected into a person. Although new methods like Moderna’s are lightning fast to prepare, they have never led to a licensed vaccine for sale.

What’s more, despite the fast start, any vaccine needs to prove that it’s safe and that it protects people from infection. Those steps are what lock in the inconvenient 18-month time line Fauci cited. While a safety test might take only three months, the vaccine would then need to be given to hundreds or thousands of people at the core of an outbreak to see if recipients are protected. That could take a year no matter what technology is employed.

Vaccine hope and hype

In late February, shares prices for Moderna Pharmaceuticals soared 30% when the company announced it had delivered doses of the first coronavirus vaccine candidate to the National Institutes of Health, pushing its stock market valuation to around $11 billion, even as the wider market cratered. The vaccine could be given to volunteers by the middle of this month.

The turnaround speed was, in fact, awesome. As Bancel put it, it took only 42 days “from the sequence of a virus” for his company to ship vaccine vials to Fauci’s group at the NIH.

Moderna did it by using technology in which genetic information is added to nanoparticles. In this case, the company added the genetic instructions for the “spike” protein the virus uses to fuse with and invade human cells. If injected into a person, nanoparticles like this could cause the body to immunize itself against the real contagion.

At Moderna’s offices in Cambridge, Bancel and others had been tracking the fast-moving outbreak since January. To begin their work, all they’d needed was the sequence of the virus then spreading in Wuhan, China. When Chinese scientists started putting versions online, its scientists grabbed the sequence of the spike protein. Then, at its manufacturing center in Norwood, Massachusetts, it could start making the spike mRNA, adding it to lipid nanoparticles, and putting the result in sterile vials.

During the entire process, Moderna didn’t need—or even want—actual samples of the infectious coronavirus. “What we are doing we can accomplish with the genetic sequence of the virus. So as soon as it was posted, we and everyone else downloaded it,” Moderna president Stephen Hoge said in an interview in January.

Moderna has already made a few experimental vaccines this way, against diseases including the flu, so it could adapt the same manufacturing process to a new threat. It only needed to swap out what RNA it added. “It’s like replacing software rather building a new computer,” says Jacob Becraft, CEO of Strand Therapeutics, which is designing vaccines and cancer treatments with RNA. “That is why Moderna was able to turn that around so quickly.”

The company says its approach is safe: it has dosed about 1,000 people in six earlier safety trials for a range of infections. What it hasn’t ever shown, however, is whether its technology actually protects human beings against disease.

“You don’t have a single licensed vaccine with that technology,” a vaccine specialist named Peter Hotez, chief of Baylor University’s National School of Tropical Medicine, said in a congressional hearing on March 5, three days after the White House event.

During his testimony, Hotez, who himself developed a SARS vaccine that never reached human testing, went out of his way to ding companies for raising expectations. “Unfortunately, some of my colleagues in the biotech industry are making inflated claims,” he told the legislators. “There are a lot of press releases from the biotechs, and some of them I am not very happy about.”

Moderna did not respond to Hotez’s criticisms or to a question about whether Trump had misunderstood Bancel. “We have no comment at this time,” said Colleen Hussey, a spokesperson for the company.

Types of vaccines

There are about a half-dozen basic types of vaccines, including killed viruses, weakened viruses, and vaccines that involve injections of viral proteins. All aim to expose the body to components of the virus so specialized blood cells can make antibodies. Then, when the real infection happens, a person’s immune system will be primed to halt it.

“And all those strategies are being tried against coronavirus,” says Drew Weissman, an expert on RNA vaccines at the University of Pennsylvania. Weissman says a coronavirus “is not a difficult virus to make a vaccine against.”

Each technology has pros and cons, and some move more slowly. For instance, the French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi has lined up funding to make a more conventional vaccine which it says it will take six months to create. Tests on people couldn’t happen until 2021.

What makes mRNA vaccines different—and potentially promising—is that once a company has a way to make them, it’s fast to respond to new threats as they arise, just by altering the gene content. “That is tremendous speed, and that is something RNA vaccines enable, but no one can guarantee that those vaccines will absolutely work,” says Ron Weiss, a synthetic biologist at MIT and a cofounder of Strand. “It’s not going to happen in a couple of months. It’s not going to happen by the summer. It’s a promising but unproven modality. I am excited about it as a modality, but just as with any new modality, you have to be very careful. Do you get enough expression? Does it persist? Does it elicit any adverse responses?”

Weissman says the idea of genetic vaccines—using DNA or RNA—is 30 years old, but tests have revealed unwanted immune reactions and, in some cases, lack of potent enough effects. Those problems have not been entirely overcome, says Weissman, who invented a chemical improvement that his university licensed to Moderna and BioNTech, a German biotech he currently works with.

Moderna has published only two results so far, he says, both from safety trials of influenza vaccines, which he considers a mixed success because the vaccines didn’t generate as much immunity as hoped. Weissman believes contaminants of impure RNA in the preparation may be to blame.

“There are two stories: what we see in animals and what Moderna has put into people. What we see in animals is a really potent response, in every animal through mice and monkeys,” he says. “While the Moderna trials weren’t terrible—the responses were better than a standard vaccine—they were much lower than expected.”

Moderna’s new coronavirus vaccine candidate could run into similar problems, and even though it’s first out of the gates, it could be overtaken by more conventional vaccines if those prove more effective. “Usually when you invest in something new, you want it to be better,” he says. “Otherwise how would you replace what is old?”

Safety test

Moderna’s technology, however, is almost certain to be the first coronavirus vaccine tried in humans. The Boston Globe reported that the NIH is already recruiting volunteers for the Phase I safety trial, and the first volunteer could get a shot by mid-month at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, a city rocked by a coronavirus outbreak.

Doctors will monitor the healthy volunteers for reactions and check to see if their bodies start producing antibodies against the virus. Researchers can take their blood and see if it “neutralizes” the virus in laboratory tests. Depending on the level of antibodies in their blood serum, those antibodies should attach to the spike protein and block the virus from entering cells.

If that safety test goes smoothly, it may be possible to begin Phase 2 trials by summer to determine whether vaccinated people are protected from the contagion. However, that will involve dosing hundreds or thousands of people near an outbreak and at risk of infection, says Fauci.

“You do that in areas where there is an active infection, so you are really talking a year, a year and half, before you know something works,” Fauci said to Howard Bauchner, the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, in a podcast aired last week.

A vaccine won’t save us

As of last week, the number of coronavirus cases worldwide had surpassed 113,000, with cases in 34 US states. Over the weekend the World Health Organization again urged countries to slow the spread with “robust containment and control activities,” pointedly adding that “allowing uncontrolled spread should not be a choice of any government.”

One downside of faith in an experimental vaccine is the risk that it could lead officials to slow-walk containment steps like restricting travel or closing schools, measures that are already causing economic losses.

Another thing to look for next is whether, and how, the administration tries to fast-track the vaccine effort. Some of the executives at the White House meeting took the chance to say more government money would help pay for manufacturing plants, among other needs, while others suggested to Trump that the US Food and Drug Administration could expedite testing in some fashion.

Although no one said they wished to distribute a vaccine that has not been fully proven, by telling Trump it’s time to build factories and cut red tape, the executives may have put that idea on the table.

Fauci has since taken opportunities to warn against such a step. While the FDA has ways to speed projects, any move to skip the collection of scientific evidence and give an unproven a vaccine to healthy people could easily backfire.

That’s in part because vaccines can sometime make diseases worse, not better. Hotez says the effect is called “immune enhancement,” and that he saw it with one version of his SARS vaccine, which sickened mice.

In his podcast with JAMA, Fauci cautioned about what could occur if you “get what you think is a vaccine, and just give it to people.” Because vaccine recipients are healthy, there’s not much margin for error: “So we are not going to have a vaccine in the immediate future, which tells us we have to rely on the public measures.”

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.