Cops see an encryption problem. Spyware makers see an opportunity.

- The US Senate is set for a new hearing into encryption

- The big question: Is there new legislation mandating encryption back doors?

- Meet the Israeli company selling a tool to push people off encrypted services

Suppose you’re a cop who wants to eavesdrop on an encrypted phone call, the kind of call billions of people make all the time on WhatsApp. Old-fashioned wiretaps don’t work, since the technology underpinning encryption guarantees you’ll get nothing. You could try to hack a target’s phone and listen in—but that’s often a difficult and expensive proposition. Or you could legally demand that the company behind the service allow law enforcement a way to see the encrypted data, but that can mean a long and expensive legal battle.

This long war between law enforcement and the technology industry will continue when the US Senate opens a hearing on data encryption Tuesday morning.

The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Republican Lindsey Graham, will hold the hearing, which will deal with technology that protects everything from WhatsApp communications to the data on your iPhone. Apple and Facebook privacy managers will be among those testifying next to one of the US government’s most vocal critics of encryption, Manhattan district attorney Cy Vance. The Trump administration has regularly criticized the use of cryptography, and in July Attorney General William Barr called for “lawful access” and encryption back doors that would allow officials to see encrypted private data.

Opponents say these weaken internet security and privacy across the board, but there have been pushes from both parties in Congress to expand access to encrypted data. Several years ago the committee’s vice chair, Democrat Dianne Feinstein, promoted a controversial bill to mandate government access. That bill ended up going nowhere, but the biggest question leading into Tuesday’s hearing is whether a new bipartisan bill will emerge—and if so, whether it could have the backing of the White House.

But while this hearing is the latest chapter in the decades-long conflict between government and the technology industry, some companies are using different tactics to get access to encrypted data—and they’re selling it to law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

Different tactics

Ten years ago, encryption—which deploys math to make data unreadable except by the intended recipient—was rare for ordinary users. Today, it protects the web browsing, text messages, and phone calls of billions of people around the world. That protection applies equally to democratically elected politicians and human rights activists but also to terrorists and spies, which has long driven governments to attempt to pierce encryption by both legal and technical means.

I recently met Ithai Kenan, vice president of an Israeli intelligence company called Picsix, at the Milipol security conference in Paris. Made up of Israeli intelligence veterans, Picsix is a decade-old company that specializes in data interception as a way of solving the encryption problem. (Its name is a nod to American football, and reflected in the company’s slogan: “The perfect interception.”)

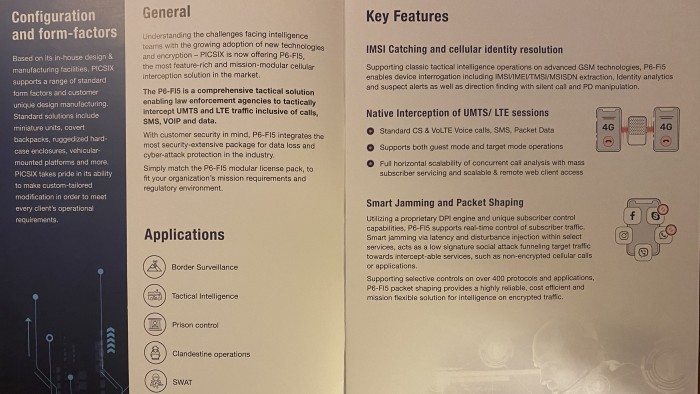

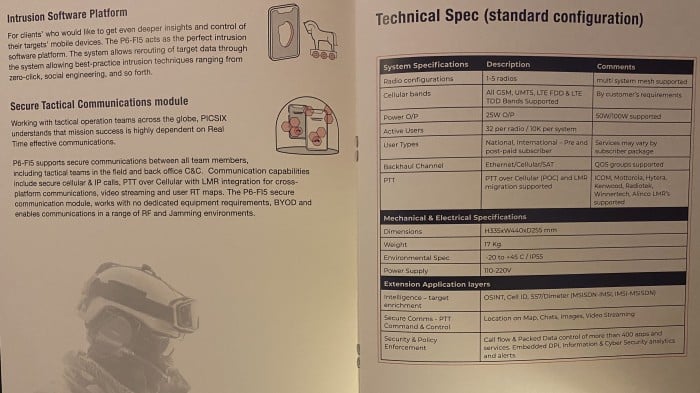

Kenan was selling the company’s newest product, a data interception and manipulation tool known as P6-FI5. The device works on GSM, 3G, and 4G cellular interception—meaning it can intercept and control both phone calls and data—and can be miniaturized to be carried inside backpacks or vehicles.

Picsix’s tool creates a fake cell tower that can fool a target’s phone into transmitting data to it. The device cannot read encrypted data, but instead tries a different tactic to get private information: making encrypted apps glitchy or even totally unusable. It’s a subtle but strong way to push a frustrated target away from a private app and toward a non-encrypted service that can easily be intercepted and eavesdropped on. The encryption itself is never broken—it is simply rendered useless.

“We can manipulate data in a very selective manner,” Kenan said. “We can do it in a very selective way so it won’t seem like you’re being manipulated. We won’t just block WhatsApp entirely. Instead, we’ll let you make a WhatsApp call, and 10 seconds in, we’ll drop it. Maybe we’ll let you make another call, and in 20 seconds we’ll drop it. After your third failed call, trust me—you’ll make a regular call, and we will intercept it. It’s a smart and cost-effective way to go about interception.”

Traffic shaping to funnel data to more advantageous terrain is a tried and trusted intelligence tactic aimed at manipulating the target into a place where it’s easier to attack. This doesn’t accomplish the same goals as compromising a victim’s phone itself, but it can be equally effective and potentially even more persistent. A Trojan horse from a company like NSO Group might get you full access to the phone of a target for millions of dollars, but it relies on a vulnerability in the code running on the device: WhatsApp could release a security update tomorrow that renders the exploit useless and the money wasted.

Picsix argues that even though its tool won’t get access to the encrypted data, its usefulness won’t be wiped out by a single update either.

“That’s why we like data manipulation,” Kenan said.

The tactic also has the capacity to work across myriad devices, because it targets the data rather than the hardware. A Samsung Galaxy S10 and an iPhone 11 are two enormously different phones: every exploit has to be tailored to that specific target.

“Because of how expensive Trojan horses are, there isn’t one manufacturer that does Trojan horses and actually supports all the different devices and manufacturers,” Kenan said. “You may have software for Android but not iOS. Let’s not even talk about all the funky devices you can find in China and India.”

That said, Picsix’s technology can also reroute target data and inject malware onto a phone that uses its fake cell tower. From that moment, those multimillion-dollar Trojan horses can, potentially, be put to use.

The bigger battle

Governments around the world have been using the tools built by companies like NSO Group and Picsix for years. There’s an entire highly capable and lucrative intelligence industry dedicated to the task.

But many top officials in Washington, DC, don’t want to have to rely on these tools to access data. Earlier this year during a security conference in New York City, Attorney General Barr called for back doors to encrypted data, and US Attorney Richard P. Donoghue pointed his finger at American tech giants.

“These companies are marketing—they deny they’re marketing, but they are marketing—that they deny access to law enforcement,” Donoghue said. “They should be held accountable.”

For years, cryptographers have warned against encryption back doors as a solution that will undermine the security benefits of strong encryption. It’s not clear what will happen in the US Senate on Tuesday, but you can expect a back-and-forth debate that looks a lot like the so-called “crypto wars” of years past.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

How Wi-Fi sensing became usable tech

After a decade of obscurity, the technology is being used to track people’s movements.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.