Inside the Microsoft team tracking the world’s most dangerous hackers

When the Pentagon recently awarded Microsoft a $10 billion contract to transform and host the US military’s cloud computing systems, the mountain of money came with an implicit challenge: Can Microsoft keep the Pentagon’s systems secure against some of the most well-resourced, persistent, and sophisticated hackers on earth?

“They’re under assault every hour of the day,” says James Lewis, vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Microsoft’s latest win over cloud rival Amazon for the ultra-lucrative military contract means that an intelligence-gathering apparatus among the most important in the world is based in the woods outside Seattle. These kinds of national security responsibilities once sat almost exclusively in Washington, DC. Now in this corner of Washington state, dozens of engineers and intelligence analysts are dedicated to watching and stopping the government-sponsored hackers proliferating around the world.

Members of the so-called MSTIC (Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center) team are threat-focused: one group is responsible for Russian hackers code-named Strontium, another watches North Korean hackers code-named Zinc, and yet another tracks Iranian hackers code-named Holmium. MSTIC tracks over 70 code-named government-sponsored threat groups and many more that are unnamed.

The rain started just before I arrived on a typical fall day in Redmond, Washington. It kept coming down for my entire visit. Microsoft headquarters is as vast and labyrinthine as any government installation, with hundreds of buildings and thousands of employees. I’d come to meet the Microsoft team that tracks the world’s most dangerous hackers.

Offense and defense

John Lambert has been at Microsoft since 2000, when a new cybersecurity reality was first setting in both in Washington, DC, and at Microsoft’s Washington state headquarters.

Microsoft, then a singularly powerful company that monopolized PC software, had only relatively recently realized the importance of the internet. With Windows XP having conquered the world while remaining shockingly insecure, the team witnessed a series of enormous and embarrassing security failures, including self-replicating worms like Code Red and Nimda. The failures affected many of Microsoft’s huge numbers of government and private sector customers, endangering its core business. Not until 2002, when Bill Gates sent out his famous memo urging an emphasis on “trustworthy computing,” did Redmond finally begin to grapple with the importance of cybersecurity.

This is when Lambert became fascinated with the offensive side of cyber.

“There’s a perfection required in the bounds of attack and defense,” Lambert told me. “To defend well, you have to be able to attack. You have to have the offensive mind-set too; you can’t just think about defense if you don’t know how to be creative about offense.”

After seeing the number of government-sponsored hacking campaigns increase, Lambert used this offensive mind-set to help drive fundamental changes in the way Microsoft approached the problem. The goal was to move from an unknowable “shadow world”—where defense teams watch, frustrated, as sophisticated hackers penetrate networks with potent “zero-day vulnerabilities”—into a domain where Microsoft can see almost anything.

“What are the superpowers of Microsoft?” Lambert remembers asking.

The answer is that its Windows operating system and other software are almost everywhere, giving Microsoft the tools to sense what happens on colossal swaths of the internet. That raises real and ongoing privacy questions we still haven’t fully grappled with. For security, however, it’s an enormous advantage.

Microsoft’s products already had Windows Error Report systems built in to try to understand general bugs and malfunctions by means of telemetry, or collecting data from any of the company’s hardware or software in use. But it was Lambert and the security teams who turned the telemetry systems into powerful security tools, transforming what was once a slow and arduous task. Previously, security teams often had to physically go around the world, find specific targeted machines, copy their hard drives, and dive into the incidents slowly. Now those machines simply reach out to Microsoft. Virtually every crash and unexpected behavior is reported to the company, which sorts through the mass of data and, often, finds malware before anyone else.

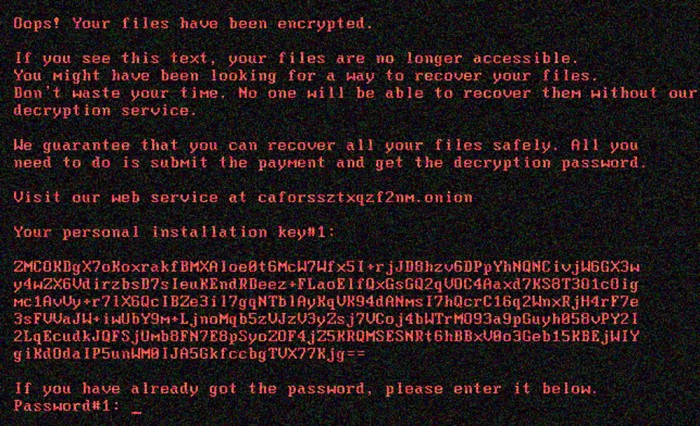

The malware known as Bad Rabbit, which in 2017 pretended to be an Adobe Flash update and then wiped a victim’s hard drive, crystallizes how Microsoft changed weakness to strength. Within 14 minutes of the ransomware’s introduction, machine-learning algorithms pieced through the data and quickly began to understand the threat. Windows Defender began blocking it automatically, well before any human knew what was happening.

“That’s the thing that nobody else has: visibility and data. The data that nobody else has is around those application crashes at the operating system and the software layer,” says Jake Williams, a former member of the National Security Agency. “Even for third-party crashes, they have telemetry around those. As you start looking at exploit targets, Microsoft has the ability through their telemetry.” That telemetry has made every Windows machine and product into a source that feeds Microsoft data and logs, instantly and worldwide, on anything unusual.

“Microsoft sees stuff that just nobody else does,” says Williams, who founded the cybersecurity firm Rendition Infosec. “We routinely find stuff, for instance, like flags for malicious IPs in Office 365 that Microsoft flags, but we don’t see it anywhere else for months.”

Connect the dots

Cyber threat intelligence is the discipline of tracking adversaries, following bread crumbs, and producing intelligence you can use to help your team and make the other side’s life harder. To achieve that, the five-year-old MSTIC team includes former spies and government intelligence operators whose experience at places like Fort Meade, home to the National Security Agency and US Cyber Command, translates immediately to their roles at Microsoft.

MSTIC names dozens of threats, but the geopolitics are complicated: China and the United States, two of the most significant players in cyberspace and the two biggest economies on earth, are virtually never called out the way countries like Iran, Russia, and North Korea frequently are.

“Our team uses the data, connects the dots, tells the story, tracks the actor and their behaviors,” says Jeremy Dallman, a director of strategic programs and partnerships at MSTIC. “They’re hunting the actors—where they’re moving, what they’re planning next, who they are targeting—and getting ahead of that.”

Tanmay Ganacharya leads advanced threat protection research on the Microsoft Defender team, which is applying data science to the mass of incoming signals in an effort to craft new layers of defense. “Because we have products across any field you can think of, we have sensors that are bringing us the right kind of signals,” he says. “The problem was, how do we actually deal with all this data?”

Microsoft, like other tech giants including Google and Facebook, regularly notifies people targeted by government hackers, which gives the targets the chance to defend themselves. In the last year, MSTIC has notified around 10,000 Microsoft customers that they’re being targeted by government hackers.

New targets

Beginning in August, MSTIC spotted what’s known as a password spraying campaign. Hackers took around 2,700 educated guesses at passwords for accounts associated with an American presidential campaign, government officials, journalists, and high-profile Iranians living outside Iran. Four accounts were compromised in this attack.

Analysts at MSTIC identified the compromises in part by tracking infrastructure Microsoft says it knows is controlled exclusively by the Iranian hacking group Phosphorus.

“Once we understand their infrastructure—we have an IP address we know is theirs that they use for malicious purposes—we can start looking at DNS records, domains created, platform traffic,” Dallman says. “When they turn around and start using that infrastructure in this kind of attack, we see it because we’re already tracking that as a known indicator of that actor’s behavior.”

After doing considerable reconnaissance work, Phosphorus tried to exploit the account recovery process by using targets’ real phone numbers. MSTIC has spotted Phosphorus and other government-sponsored hackers, including Russia’s Fancy Bear, repeatedly using that tactic to try to phish two-factor authentication codes for high-value targets.

What raised Microsoft’s alarm above normal on this occasion was that Phosphorus varied its standard operating procedure of going after NGOs and sanctions organizations. The cross-hairs shifted, the tactics changed, and the scope grew.

“This isn’t uncommon, but the difference here was that this was on a significantly larger scale than we had seen before,” Dallman says. “They target these types of people frequently, but it was the scale and the massive amount of reconnaissance work that they had done for this campaign [that was different]. And then ultimately it came down to the individuals they were targeting, including the individual on the presidential campaign.”

Microsoft’s sleuthing ultimately pointed the finger at Iranian hackers for targeting presidential campaigns including, Reuters reported, Donald Trump’s 2020 reelection operation.

“We’ve seen the patterns.”

In Lambert’s two decades at Microsoft, the tools and weapons of the cyber domain have proliferated to dozens more countries, hundreds of capable cybercrime groups, and—increasingly—an industry of private-sector companies selling exploits internationally to buyers willing to pay top dollar.

“Proliferation means a much broader range of victims,” Lambert says. “More actors to track.”

That is showing up in political hacks. One consequence of the 2016 US election is a rise in the sheer number of players fighting to hack political parties, campaigns, and think tanks, not to mention government itself. Election-related hacking has typically been the province of the “big four”—Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea. But it’s spreading to other countries, although the Microsoft researchers declined to specify what they’ve seen.

“What is different is that you’re getting additional countries joining the fray that weren’t necessarily there before,” says Jason Norton, a principal project manager on MSTIC. “The big two [Russia and China]—now, we can say they’ve been historically going after this since well before the 2016 election. But now you’re getting to see additional countries do that—poking and prodding the soft underbelly in order to know the right pieces to have an influence or impact in the future.”

“The field is getting crowded,” Dallman agrees. “Actors are learning from each other. As they learn tactics from the more prominent names, they turn that around and use them.”

The upcoming election is different, too, in that no one is surprised to see this malicious activity. Leading into 2016, Russian cyber activity was greeted with a collective dumbfounded naïveté, contributing to paralysis and an unsure response. Not this time.

“The difference really comes down to what we know is going to happen,” Dallman explains.

“Then, it was more of an unknown, and we weren’t sure how the tactics would develop. Now we know; we’ve seen the patterns. You saw them in 2016, you saw what they did in Germany, you saw them in the French elections—all following the same MO. The 2018 midterms, too—to a lesser degree, but we still saw some of the same MO, the same actors, the same timing, the same techniques. Now we know, going into 2020, that this is the MO we’re looking for. And now we’ve started to see other countries come out and start doing other tactics.”

The new normal is that industry cyberintelligence shops tend to lead the way in this type of public security activity while government follows.

In 2016, it was CrowdStrike that first investigated and pointed the finger at Russian activity aiming to interfere with the American election. The US law enforcement and intelligence community later confirmed the company’s findings and eventually, after Robert Mueller’s investigation, indicted Russian hackers and detailed Moscow’s campaign.

At a total size of over $1 trillion, Microsoft is an order of magnitude larger, bringing enormous resources to the security challenge. And the tech giant has another great advantage: it has eyes, ears, and software everywhere. That, as Lambert might say, is its superpower.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

How Wi-Fi sensing became usable tech

After a decade of obscurity, the technology is being used to track people’s movements.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.