High-Resolution 3-D Scans Built from Drone Photos

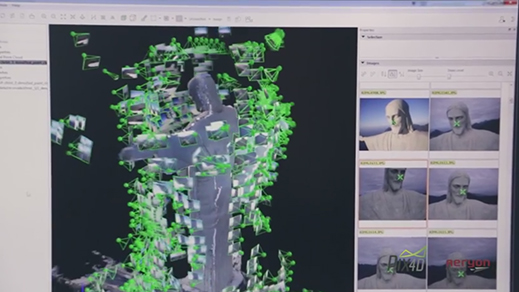

The 30-meter tall statue of Christ overlooking Rio de Janeiro from a nearby mountain was under construction for nine years before its opening in 1931. It took just hours to build the first detailed 3-D scan of the monument late last year, using more than 2,000 photos captured by a small drone that buzzed all around it with an ordinary digital camera. The statue’s digital double was unveiled last month, and is accurate to between two and five centimeters, enough to capture individual mosaic tiles.

The project was intended to help efforts to preserve the statue and to demonstrate how drones could lead to a dramatic increase in high-resolution 3-D replicas of buildings, terrain, and other objects. Being able to easily and frequently capture detailed 3-D imagery could have many uses, such as speeding up construction projects and helping Hollywood make better special effects, says Christoph Strecha, CEO and cofounder of Pix4D, the Swiss company that led the project. It collaborated with drone manufacturer Aeryon Labs and researchers at PUC University of Rio de Janeiro.

Mapping tools from companies including Google and Apple have made outdoor 3-D imagery commonplace in recent years. But they are mostly built with 3-D data from aircraft carrying expensive equipment. The 3-D shape of buildings and terrain is most often captured using a technique called lidar, which uses lasers. The photo-real 3-D models of cities in Apple’s “flyover” mode are made by processing images captured by a complex and expensive array of cameras (see “Ultrasharp 3-D Maps”). Both techniques rely on very accurate GPS technology.

Drones don’t have very reliable GPS fixes by comparison, and can’t carry large sensors or cameras. But they are cheap, and Pix4D’s software can build highly accurate models by comparing many different overlapping photos, says Strecha. In fact, using lidar would have been impossible with the Rio statue, Strecha says, because of its size, shape, and location.

Other projects have also been weaving 3-D models from drone photos. Researchers led by Horst Bischof, a professor at the Technical University of Graz, Austria, are developing software that extracts information from such images. For example, for a company that restores old buildings, the researchers made a version of the software that calculates measurements necessary for producing custom-fit thermal insulation.

With the image processing more or less a solved problem, the ambitions of drone scanning will depend more on how well drones can be controlled or coӧrdinated in challenging conditions like the winds around Rio’s Christ, or to cover larger areas, says Carl Salvaggio, a professor at Rochester Institute of Technology’s Center for Imaging Science. “Drones are good for small-scale projects but traditional aircraft offer the time in the air to collect whole cities,” he says. “Perhaps when there are ‘armies’ of drones in the air, we will see a different landscape emerge.”

Christ the Redeemer Rio by Pix4D on Sketchfab

Corcovado and Christ the Redeemer by Pix4D on Sketchfab

-->

Deep Dive

Artificial intelligence

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

What’s next for generative video

OpenAI's Sora has raised the bar for AI moviemaking. Here are four things to bear in mind as we wrap our heads around what's coming.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.