CRISPR experts are calling for a global moratorium on heritable gene editing

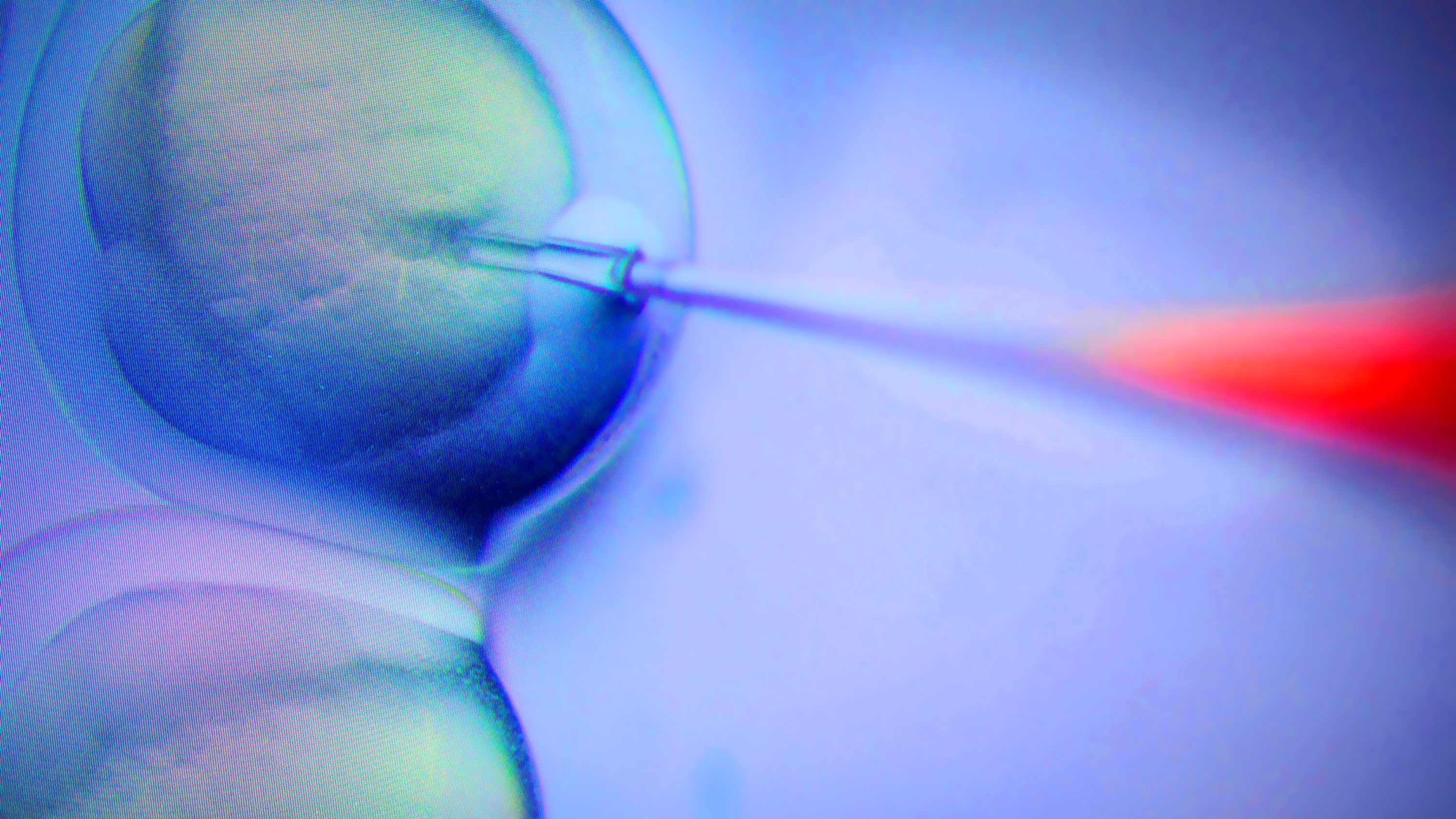

After the first International Summit on Human Gene Editing in December 2015, a statement was released. The organizers were unanimous in agreeing that the creation of genetically modified children was “irresponsible” unless we knew for sure it was safe.

Well, a fat lot of good that did. As was revealed in November last year, Chinese scientist He Jiankui edited embryos to create two genetically engineered babies. Other groups are now actively looking to use the technology to enhance humans.

This has prompted some of the biggest names in gene editing (some of whom signed the 2015 statement) to call for a global moratorium on all human germline editing—editing sperm or egg cells so that the changes are hereditary.

In an open letter in Nature this week, major players in CRISPR’s development, including Emmanuelle Charpentier, Eric Lander, and Feng Zhang, have been joined by colleagues from seven different countries to call for a total ban on human germline editing until an international framework has been agreed on how it should be treated. They suggest five years "might be appropriate." The US National Institutes of Health has also backed the call.

The signatories hope a voluntary global moratorium will stop the next He Jiankui from suddenly springing another unwelcome surprise.

The group says that this moratorium period will allow time to discuss the “technical, scientific, medical, societal, ethical, and moral issues that must be considered” before the technique can be used. Countries that decide to go ahead and allow germline editing should do so only after notifying the public of the plan, engaging in international consultation “about the wisdom of doing so,” and making sure that there is a “broad societal consensus” in the country for starting on that path, they say.

“The world might conclude that the clinical use of germline editing is a line that should not be crossed for any purpose whatsoever,” the group says. “Alternatively, some societies might support genetic correction for couples with no other way to have biologically related children, but draw a line at all forms of genetic enhancement. Or, societies could one day endorse limited or widespread use of enhancement.”

The letter’s signatories suggest that germline research should be allowed so long as there is no intention to implant embryos and produce children. Using CRISPR to treat diseases in non-reproductive somatic cells (where the changes would not be heritable) should also be fine so long as any adults participating have given their informed consent. Genetic enhancement should not be allowed at this time, and no clinical application carried out unless its “long-term biological consequences are sufficiently understood—both for individuals and for the human species,” they write.

We still don’t know what the majority of our genes do, so the risks of unintended consequences or so-called off-target effects—good or bad—are huge. The loss of the CCR5 gene that He was targeting to protect children from HIV, for example, has been implicated in increased complications and death from some viral infections.

Changes in a genome might have unforeseen outcomes in future generations as well. “Attempting to reshape the species on the basis of our current state of knowledge would be hubris,” the letter reads.

The proposed moratorium and global framework are only voluntary— and unlikely to stop rogue scientists. But the signatories feel an outright ban and regulation would be too “rigid.” Instead, they hope their proposal will “place major speed bumps in front of the most adventurous plans to reengineer the human species.”

Indeed, chastened by the He experience, China’s health ministry is already creating some speed bumps of its own. Last week it drafted guidelines that will force the nation’s scientists to seek approval from authorities before carrying out any risky procedures such as germline editing.

(On March 18 we amended the second paragraph so attribution for the original story was clearer.)

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

Google helped make an exquisitely detailed map of a tiny piece of the human brain

A small brain sample was sliced into 5,000 pieces, and machine learning helped stitch it back together.

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.