Despite CRISPR baby controversy, Harvard University will begin gene-editing sperm

In the wild uproar around an experiment in China that claimed to have created twin girls whose genes were altered to protect them from HIV, there’s something worth knowing—research to improve the next generation of humans is happening in the US, too.

In fact, it’s about to happen at Harvard University.

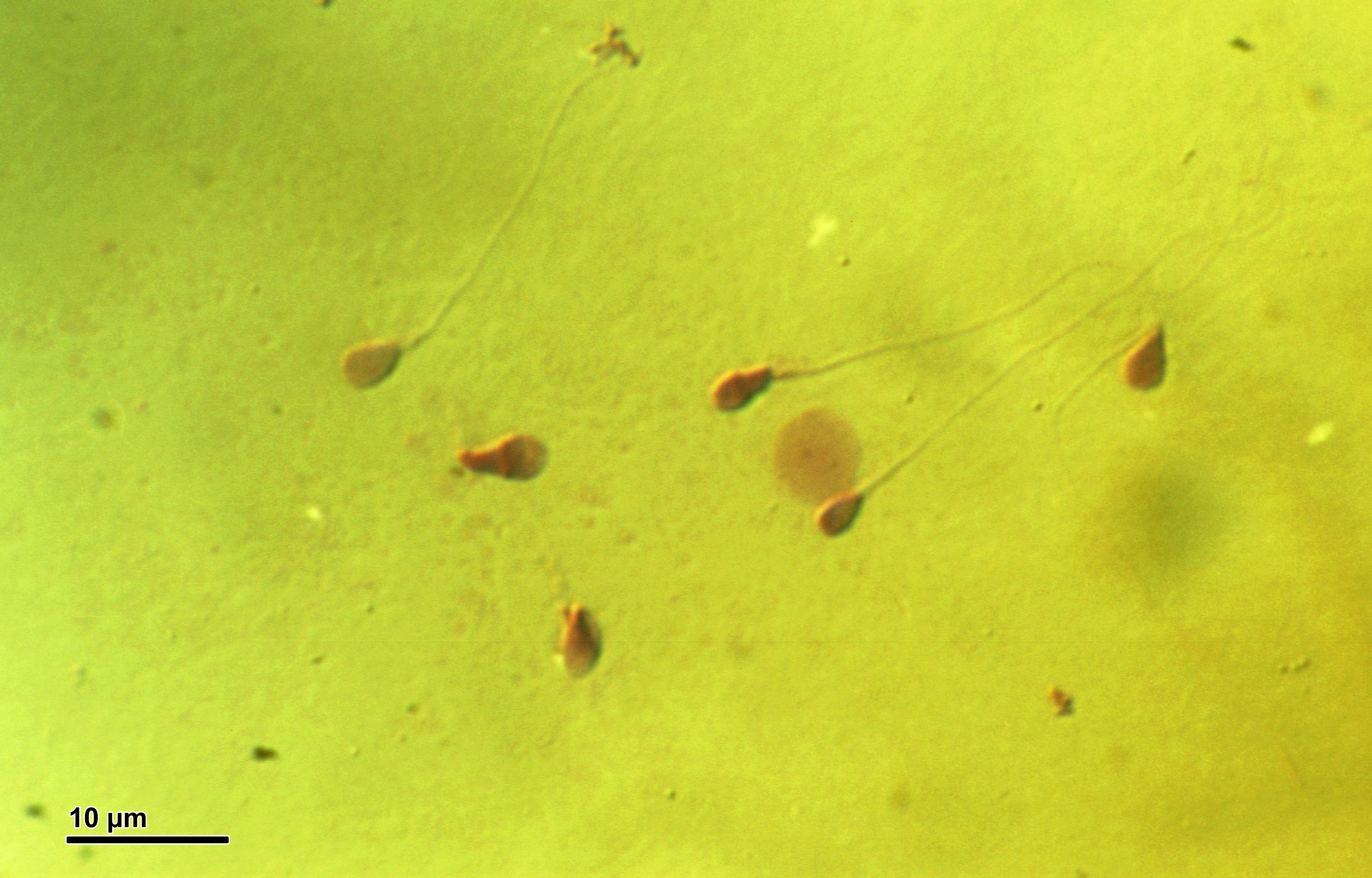

At the school’s Stem Cell Institute, IVF doctor and scientist Werner Neuhausser says he plans to begin using CRISPR, the gene-editing tool, to change the DNA code inside sperm cells. The objective: to show whether it is possible to create IVF babies with a greatly reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

To be clear, there are no embryos involved—no attempt to make a baby. Not yet. Instead, the researchers are practicing how to change the DNA in sperm collected from Boston IVF, a large national fertility-clinic network. This is still very basic, and unpublished, research.

Yet in its purpose the project is similar to the work undertaken in China and raises the same fundamental question: does society want children with genes tailored to prevent disease?

Since Sunday, when the CRISPR babies claims was made public, medical bodies and experts have ferociously condemned He Jiankui, the Chinese scientist responsible. There is evidence his experiments—now halted—were carried forward in an unethical, deceptive manner that may have endangered the children he created. China’s vice minister of science and technology, Xu Nanping, said the effort “crossed the line of morality and ethics and was shocking and unacceptable.”

Amid the condemnation, though, it was easy to lose track of what the key experts were saying. Technology to alter heredity is for real. It is improving very quickly, it has features that will make it safe, and much wider exploratory use to create children could be justified soon.

That was the message delivered at a gene-editing summit in Hong Kong on Wednesday, November 28, by Harvard Medical School dean George Daley, just ahead of He’s own dramatic appearance on the stage (see video starting at 1:15:30).

Astounding some listeners, the Harvard doctor and stem-cell researcher didn’t condemn He but instead characterized the Chinese actions as a wrong turn on the right path (see video). “The fact that it is possible that the first instance of human germ-line editing came forward as a misstep should in no way lead us to stick our heads in the sand,” Daley said. “It’s time to ... start outlining what an actual pathway for clinical translation would be.”

By germ-line editing, Daley means editing sperm, eggs, or embryos—anything that, if you alter its DNA, could convey the change to future generations. While other voices demanded a ban on germ-line editing, Daley and the other members of the summit’s leadership defended it. Their final statement said medicine’s daring and troubled project to modify humans in an IVF dish should move forward.

“It’s absolutely clear this is a transformative scientific technology with the power for great medical use.” Daley said.

Harvard project

Germ-line editing could be used, Daley said—and potentially should be used—to shape the health of tomorrow’s kids. By editing germ cells, it will be possible to remove mutations that cause childhood cancer or cystic fibrosis. Other genetic edits could endow children with protection against common diseases. On Daley’s list of potentially acceptable genes to edit was CCR5, the very gene that He altered in the twins.

At Harvard, Neuhausser says he and a research fellow, Denis Vaughan, will in the next few weeks begin editing sperm to change a gene called ApoE, which is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s risk. A person who inherits two copies of the high-risk version of the gene has about a 60% lifetime risk of getting Alzheimer’s.

Neuhausser, an Austrian fertility doctor who came to the US to do his research and practice at Boston IVF, predicts that in not so many years, embryos will be deeply analyzed, selected, and in some cases altered with CRISPR before they are used to create a pregnancy. “In the future, people will go to clinics and get their genomes tested, and have the healthiest baby they can have,” he says. “I think the whole field will switch from fertility to disease prophylaxis”—preventing illness.

To alter the DNA inside sperm cells, the team is using a clever new version of CRISPR called base editing, developed by another Harvard scientist, David Liu. Instead of breaking open the double helix, base editing can flip a single genetic letter from, say, G to A. One such molecular tweak is enough to turn a the riskiest version of the ApoE gene into the least risky.

“It’s one letter, G to A. You take it from risk to non-risk,” says Neuhausser.

Backlash

You know what is risky? Speaking to journalists these days about how you are altering the germ line. But Neuhausser hasn’t ever shied from telling me what’s going on in the lab.

And lack of transparency is one reason the Chinese experiment is so troubling. It was done secretly, and ignored China’s rules forbidding such work. “The problem is that it’s going to make things much harder for everyone else following the rules if you jump so far ahead without proper approvals,” says Neuhausser. “That is the main concern. I don’t think the research is controversial, but everyone agrees it should be kept away from patients for now.”

The debate has already caught the attention of regulators. Scott Gottlieb, the head of the US Food and Drug Administration, tweeted on Wednesday that “certain uses of science should be judged intolerable, and cause scientists to be cast out. The use of CRISPR to edit human embryos or germ line cells should fall into that bucket.” In an interview with BioCentury, Gottlieb further specified that the restriction should apply if the cells are “for reproduction.”

Right now, Gottlieb can’t cast out people, like Neuhausser, who are doing basic research. Sperm, like dot-size IVF embryos, don’t have much in the way of legal rights in the US. But he can frighten scientists, make their work harder, and drive the work overseas.

Already, Neuhausser works under many restrictions. Public funding for embryo research from the National Institutes of Health is forbidden. In Massachusetts, unlike some other states, it is also illegal to make an embryo just to study it.

That means if the time comes to test the CRISPR sperm to make an embryo, the research will have to move away from Boston. Neuhausser was in China last month exploring the possibilities of making research embryos there. So far, those plans haven’t come together.

For now, ApoE is a toy example, one to try in the lab to test the technology and its potential. It’s not certain yet whether changing this gene would alter a child’s risk of Alzheimer’s later in life. Despite very strong links to the brain disease, there is no rock-solid proof that ApoE is a cause. “It’s one of the main risk factors for Alzheimer’s, although no one has shown causality,” says Neuhausser. “The point is to show the principle.”

But slashing a newborn’s lifelong risk of Alzheimer’s would be a huge deal. So would the ability to fix mutations that cause Lou Gehrig’s disease, another illness the team is looking into. Neuhausser expects it will eventually be routine to improve the DNA of sperm or embryos—and the people they turn into—in fundamental ways.

“The big question is when is it ready for prime time,” says Alan Penzias, the endocrinologist who oversees research at Boston IVF. “I would say we are a few years away. But that sounds pretty close to me, to tell you the truth. It is something that we would be happy to do, and we would like to do in a responsible way.”

Saving the species

With Boston IVF, Neuhausser has been carrying out a survey of doctors and hundreds of patients about what they think. “For treating or preventing disease, pretty much everyone agrees,” he says—that is, they are for it.

People do draw the line at things like increasing height or changing eye color, with only a tiny percentage thinking it’s a good idea. Neuhausser admits someone might do that too, eventually. “Like any technology, there will be misuses,” he says. “But it’s important that we return to a rational approach, recognizing that this has huge potential and huge risks. The problem is that when people get scared, things get shut down. That is why people are nervous about He—he’s hurting everyone else.”

To anyone who wants to end this line of research, the Harvard doctors have one last ace to play. They say germ-line editing might be an important technology to have for civilization’s sake.

What if a new killer virus arises and sweeps the world? Maybe there will be no vaccine but some people will be able to resist it thanks to their genes, as some fared better with the Black Death in medieval times. Wouldn’t we want to then give the genetic antidote to all members of the next generation?

“This is a technology that could save the species, potentially,” says Neuhausser. In his speech in Hong Kong, Daley also referenced the potential defense against future disease.

“We as a species need to maintain the flexibility to face future threats, to take control of our heredity,” he said.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.