US military wants to know what synthetic-biology weapons could look like

A study ordered by the US Department of Defense has concluded that new genetic-engineering tools are expanding the range of malicious uses of biology and decreasing the amount of time needed to carry them out.

The new tools aren’t in themselves a danger and are widely employed to create disease-resistant plants and new types of medicine. However, rapid progress by companies and university labs raises the specter of “synthetic-biology-enabled weapons,” according to the 221-page report.

The report, issued by the National Academies of Sciences, is among the first to try to rank national security threats made possible by recent advances in gene engineering such as the gene-editing technology CRISPR.

“Synthetic biology does expand the risk. That is not a good-news story,” says Gigi Gronvall, a public health researcher at Johns Hopkins and one of the report’s 13 authors. “This report provides a framework to systematically evaluate the threat of misuse.”

Experts are divided on the perils posed by synthetic biology, a term used to describe a wide set of techniques for speeding genetic engineering. In 2016, the US intelligence community placed gene editing on its list of potential weapons of mass destruction.

“Many different groups have written and spoken about the topic, with a wide spread of opinion,” says D. Christian Hassell, deputy assistant secretary of defense for chemical and biological defense, who commissioned the report in order to obtain a “consensus opinion from among the top leaders and thinkers” in the field.

Hassell says the military’s current view is that “synbio is not a major threat issue at the moment” but bears preparing for, in part because defenses like vaccines can take years to develop.

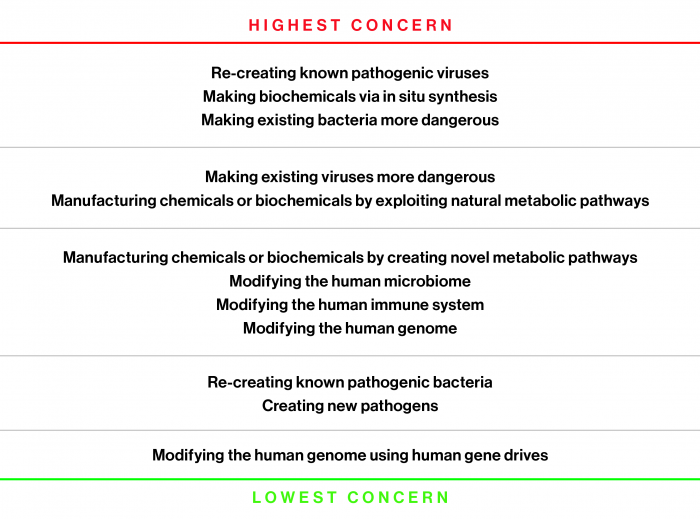

The current report attempted to weigh potential threats by considering factors such as the technical barriers to implementation, the scope of casualties, and the chance of detecting an attack. It found that while “some malicious applications of synthetic biology may not seem plausible right now, they could become achievable with future advances.”

Among the risks the authors termed of “high concern” is the possibility that terrorists or a nation-state could re-create a virus such as smallpox. That is a present danger because a technology for synthesizing a virus from its DNA instructions has previously been demonstrated.

The evaluation process shed light on some risks the authors called unexpected. In one scenario, the report imagined how ordinary human gut bacteria could be engineered to manufacture a toxin, an idea ranked as highly worrisome in part because such an attack, like a computer virus, could be difficult to uncover or attribute to its source.

Among the weapons imagined, several involved CRISPR, a versatile gene-editing tool invented only six years ago, which the report said could be introduced into a virus to cut human DNA and cause cancer. If scientists can alter animals to create disease, “it follows that [the] genomes of human beings could be similarly modified,” according to the report.

In its analysis, the committee downgraded other threats. Attempts to construct entirely novel man-made viruses, for instance would be hobbled by scientific unknowns, at least for now.

The US military, which asked for the study, is already among the largest funders of synthetic biology. Although its research is defensive in nature, technical reports such as this one, which imagine future weaponry, could generate anxiety in other nations, says Filippa Lentzos, a senior research fellow in biosecurity at King’s College London.

“You don’t want to start a new bioweapons race. The field needs to ask itself who is driving the agenda, and how does this look from the outside,” she says. “Synthetic biology has a problem, which is that much of its funding comes from the military.”

Historically, the US and other countries have worried most about specific germs such as smallpox, including them on a list of “select agents” whose possession is tightly controlled.

As the biotech tool box grows, however, the list-based approach to security is no longer seen as sufficient.

According to the report, the US must now also track “enabling developments” including methods, widely pursued by industry, to synthesize DNA strands and develop so-called “chassis” organisms designed to accept genetic payloads.

“The US government should pay close attention to this rapidly progressing field, just as it did to advances in chemistry and physics during the Cold War era,” says Michael Imperiale, a microbiologist at the University of Michigan and chair of the committee behind the publicly available report, titled Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.