We’re about to kill a massive, accidental experiment in reducing global warming

Studies have found that ships have a net cooling effect on the planet, despite belching out nearly a billion tons of carbon dioxide each year. That’s almost entirely because they also emit sulfur, which can scatter sunlight in the atmosphere and form or thicken clouds that reflect it away.

In effect, the shipping industry has been carrying out an unintentional experiment in climate engineering for more than a century. Global mean temperatures could be as much as 0.25 ˚C lower than they would otherwise have been, based on the mean “forcing effect” calculated by a 2009 study that pulled together other findings (see “The Growing Case for Geoengineering”). For a world struggling to keep temperatures from rising more than 2 ˚C, that’s a big helping hand.

And we’re about to take it away.

In 2016, the UN’s International Maritime Organization announced that by 2020, international shipping vessels will have to significantly cut sulfur pollution. Specifically, ship owners must switch to fuels with no more than 0.5 percent sulfur content, down from the current 3.5 percent, or install exhaust cleaning systems that achieve the same reduction, Shell noted in a brochure for customers.

There are very good reasons to cut sulfur: it contributes to both ozone depletion and acid rain, and it can cause or exacerbate respiratory problems.

But as a 2009 paper in Environmental Science & Technology noted, limiting sulfur emissions is a double-edged sword. “Given these reductions, shipping will, relative to present-day impacts, impart a ‘double warming’ effect: one from [carbon dioxide], and one from the reduction of [sulfur dioxide],” wrote the authors. “Therefore, after some decades the net climate effect of shipping will shift from cooling to warming.”

Sulfur pollution from coal burning has a similar effect. Some studies suggest that China’s surge in coal consumption over the last decade partly offset the recent global warming trend (though coal does have a strong net warming effect).

It’s difficult to estimate how much the new rule could affect temperatures. We don’t know enough about cloud physics and the behavior of atmospheric particles, nor how diligently the shipping industry will comply with the new rule, says Robert Wood, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington.

Another wrinkle is that ships emit other particles that can sometimes also stimulate cloud droplets to form, including black carbon, a major component of soot. Removing the sulfur from the fuel could alter the size and quantity of these particles, which could affect clouds as well, says Lynn Russell, a professor of atmospheric science at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

“So we can’t really say exactly what the change will be,” says Russell, though she adds that the rule change is “likely” to produce a warming effect on balance.

The upcoming change does offer a different way of thinking about intentional efforts to cool the climate, known as geoengineering, according to some proponents of research in this area. Rather than some radical experiment, deliberate geoengineering could instead be seen as a way of continuing to do what we’ve been doing inadvertently with ships, but in a safer way.

Sulfur emissions cool the planet in two ways, directly and indirectly. The direct way is that when sulfur dioxide is further oxidized in the atmosphere, it can form particles that reflect sunlight back into space. This happens in large volcanic eruptions, which can release tens of millions of tons of sulfur dioxide.

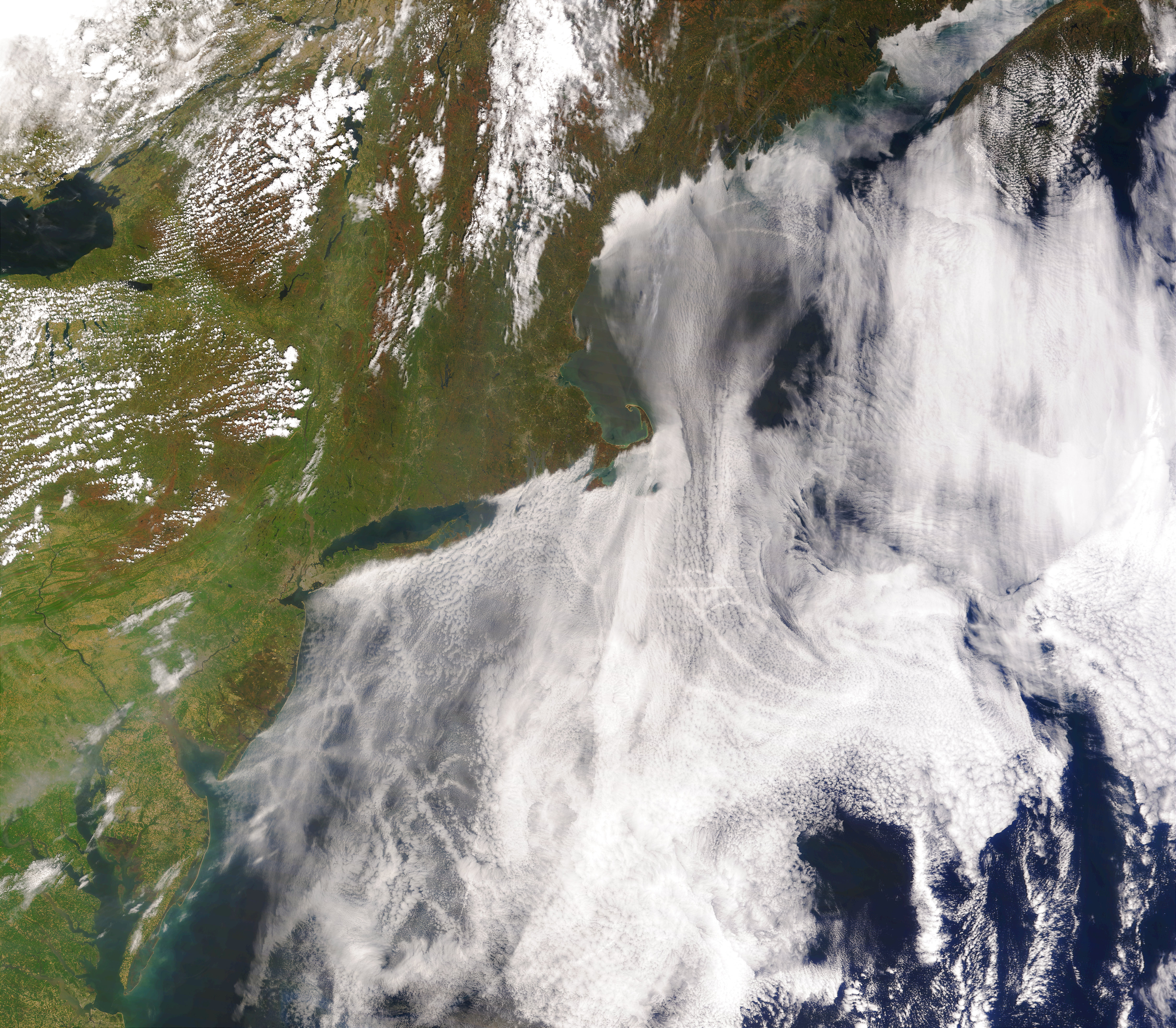

The indirect way is that sulfur particles can also act as nuclei around which cloud droplets form. Clouds, too, reflect more sunlight. You can see this in satellite images, which show lines of white clouds above the ocean along busy shipping lanes.

Geoengineering researchers have explored both processes, but with less toxic particles, as potential ways to alter the climate (see “Scientists Consider Brighter Clouds to Preserve the Great Barrier Reef”).

For instance, researchers with the Marine Cloud Brightening Project, centered at the University of Washington, have spent years studying the possibility of spraying tiny salt particles into the sky along coastlines to induce cloud droplets to form. The group has spent the last few years attempting to raise several million dollars to build the sort of sprayers that would be needed, in the hopes of carrying out small-scale field experiments somewhere along the Pacific coastline.

Both Russell and Wood said the upcoming rule change could also offer a chance to conduct some basic climate science by observing the interactions between airborne particles and clouds. Those insights could make climate simulations more accurate—how clouds behave is one of the least understood parts of the system, Wood says—as well as informing the debate about whether and how to carry out geoengineering.

But that all depends on whether scientists can get funding for such research, which will require more frequent satellite observations and surface sensors. Ideally, the research should start before the new rule goes into effect to ensure an accurate picture of how things change.

“We’re approaching dangerous thresholds of temperature increases, so an additional bump of 0.1 or 0.2 degrees is something that we as a civilization should be watching really, really closely,” says Kelly Wanser, principal director with the Marine Cloud Brightening Project.

Whether the money will be available is less clear. Certain nations have been increasing funding levels for climate research. But it’s become far more difficult to secure such grants in the United States under the Trump administration, which specifically sought to cut NASA programs that monitor clouds and airborne particles.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.