Smartphone-Controlled Cells Could Pump Insulin for Diabetics

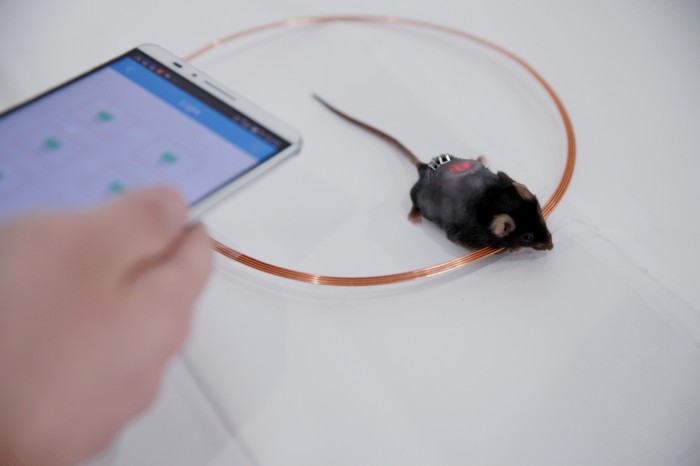

Scientists in China have used a smartphone and a technique called optogenetics to precisely control cells to deliver insulin to diabetic mice. The approach could be used to continuously monitor blood glucose levels in human diabetics and automatically produce necessary insulin, a hormone that converts sugar from food into energy the body can use.

The researchers engineered human cells with a light-sensitive gene that is found in plants and produces insulin on cue when activated by wirelessly powered red LED lights. They inserted those lights and the designer cells onto small, flexible discs that were then grafted onto the backs of mice.

A customized Android-based phone app turns on the LED lights and adjusts the intensity of the light. The researchers exposed the diabetic mice to about four hours of light each day and were able to stabilize normal insulin production in the bloodstream for 15 days.

Optogenetics is an emerging field that uses light-sensitive proteins to regulate biological activities in the body. The technique has been envisioned as a way to treat a range of diseases, including Parkinson’s and schizophrenia. The first human test of optogenetics is under way to restore vision to patients with retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye condition that leads to blindness.

The researchers, who describe the insulin delivery approach in Science Translational Medicine, say the system was inspired by the “smart home” concept, which involves lighting, heating, and electronic devices that communicate with one another and can all be controlled remotely with phone or computer apps. They say the remote-controlled cells could “pave the way for a new era of personalized, digitalized, and globalized precision medicine.”

Haifeng Ye, a senior author of the paper and a professor at East China Normal University in Shanghai, says his goal is a “fully automatic blood glucose monitor and diabetes therapy system” that could continuously monitor diabetes 24 hours a day and share the data via smartphones.

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas doesn’t produce enough insulin, a hormone necessary to convert sugar, or glucose, into energy. Currently people with type 1 diabetes need to take several insulin injections every day or wear an insulin pump that delivers the hormone through a plastic tube inserted into the skin. About 1.25 million children and adults in the U.S. have type 1 diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association.

It’s still early days for optogenetics. Two of the main challenges are which type of light frequency to use and how to beam this light at the right intensity to stimulate cells.

In people, similar results might be achieved with an LED bracelet instead of implanted discs in the skin, says Mark Gomelsky, a molecular biologist at the University of Wyoming who reviewed Ye’s paper and authored an article about it. The engineered cells would still need to be injected separately, and it’s not clear how often that would be required in people.

Gomelsky says the Chinese team’s technique may not be the best approach to treating type 1 diabetes, especially since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last year approved the first fully automated insulin pump. But he says remote-controlled cells engineered to produce genetically encoded drugs could be used to treat other diseases.

Another possible problem with a phone-controlled therapy is security. Ye acknowledged that the app may be vulnerable to hacking but says software engineers could easily solve that by installing an encryption key.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.