Hotter Days Will Drive Global Inequality

Extreme heat, it turns out, is very bad for the economy. Crops fail. People work less, and are less productive when they do work.

That’s why an increase in extremely hot days is one of the more worrisome prospects of climate change. To predict just how various countries might suffer or benefit, a team of scientists at Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley, have turned to historical records of how temperature affects key aspects of the economy. When they use this data to estimate how various countries will fare with a warming planet, the news isn’t good.

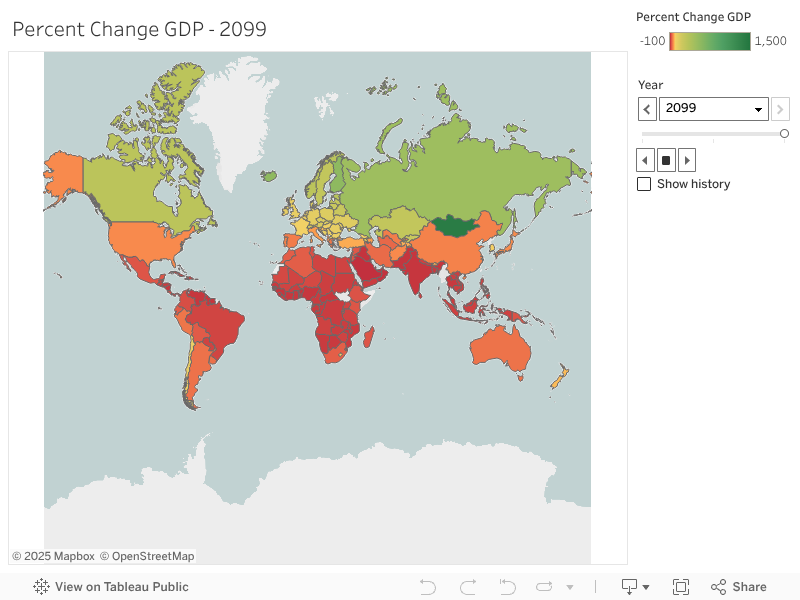

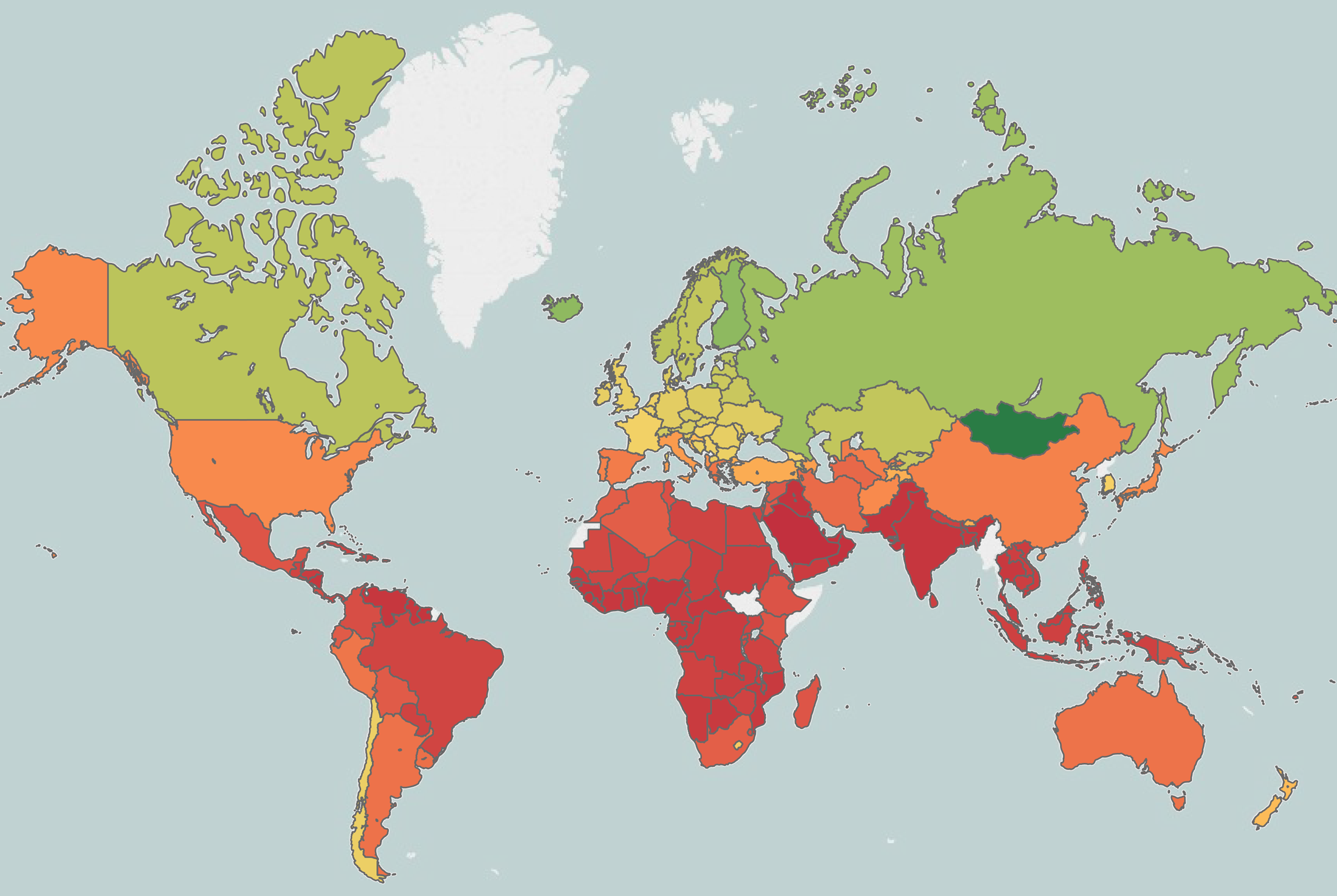

The average global income is predicted to be 23 percent less by the end of the century than it would be without climate change. But the effects of a hotter world will be shared very unevenly, with a number of northern countries, including Russia and much of Europe, benefiting from the rising temperatures. The uneven impact of the warming “could mean a massive restructuring of the global economy,” says Solomon Hsiang, a professor at the Goldman School of Public Policy at Berkeley, one of the researchers who have painstakingly documented the historical impact of temperature. Even by 2050 (see map), the variation in the economic fates of countries is striking.

Because poorer countries, including those in much of South America and Africa, already tend to be far hotter than what’s ideal for economic growth, the effect of rising temperatures will be particularly damaging to them. Average income for the world’s poorest 60 percent of people by century’s end will be 70 percent below what it would have been without climate change, conclude Hsiang and his coauthors in a recent Nature paper. The result of the rising temperatures, he says, “will be a huge redistribution of wealth from the global poor to the wealthy.”

Change in gross domestic product per capita relative to a world without global warming

Hotter weather is just one of the effects of climate change; shifts in rainfall and an increase in severe weather like hurricanes are among the others. But by analyzing temperatures alone, Hsiang and his coworkers have provided more precise estimates of how climate change could affect the economy. It turns out, Hsiang says, that temperature has a surprisingly consistent effect on different economic inputs: labor supply, labor productivity, and crop yields all drop off dramatically between 20 °C and 30 °C. “Whether you’re looking at crops or people, hot days are bad,” he says. “Even in the richest and most technologically advanced nation in the world, you will see [the negative effects],” he says, citing data showing that a day over 30 °C in an average U.S. county costs each resident $20 in unearned income. “It’s real money.”

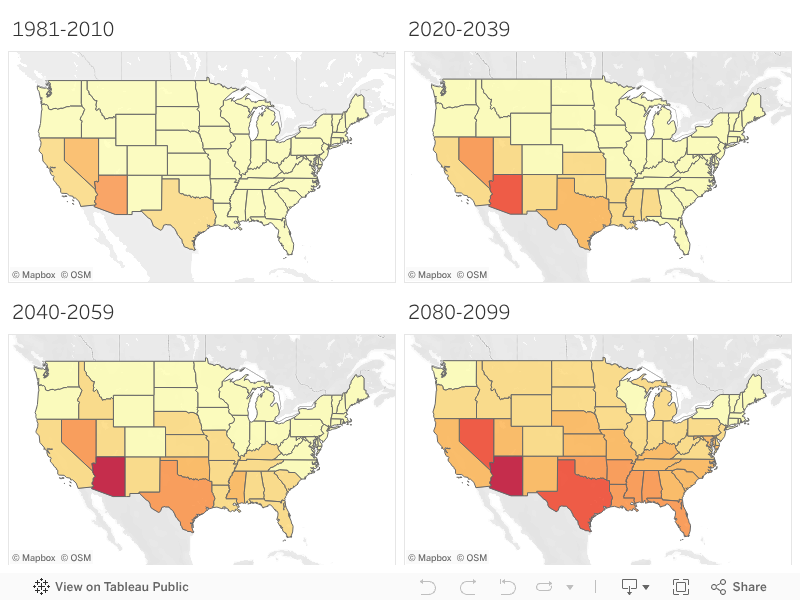

The number of days above 95 °F (35 °C) will rise dramatically in many parts of the United States if climate change continues unabated

Of course, the idea that hot temperatures affect agriculture and the way we work and feel is not new. Indeed, Hsiang points to studies done in the early 20th century on the optimum temperatures for factory workers and soldiers. But he and his colleagues have quantified how changes in temperature alter overall economic productivity for entire countries.

Hsiang and his coworkers examined both the annual economic performance in each country and the average yearly temperatures from 1960 to 2010. Then they used advanced statistical techniques to isolate temperature effects from other variables, such as changes in policies and financial cycles. Such analysis, he says, is possible because much more historical data is available, and computational power has increased enough to handle it. Then, by using climate models to project future temperatures, the researchers were able to estimate economic growth over the rest of the century if these historical patterns hold true.

Hsiang has also looked at how hot temperatures affect social behaviors and health, concluding that they increase violence and mortality (see charts). What he calls his “obsession” with the social effects of temperature can be traced to his training in the physical sciences. Temperature plays an essential and obvious role in chemistry and physics, but its effects on society and human behavior have been less appreciated. And yet, as his recent work has confirmed, the climate “is fundamental to our economy,” says Hsiang. Now he’s hoping to provide new understanding of just how an increasingly hot world will affect our future prosperity.

Hot Tempers, Poor Yields, and Sluggish Economies

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.