Tiny Glue Guns to Patch Surgical Holes

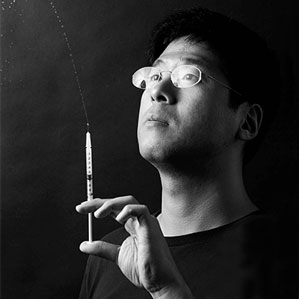

You’re in the ER with appendicitis. Surgeons can remove your appendix through a few three-fourth-inch openings, but the bulky sutures and staples they use to close internal incisions are difficult and time-consuming to manipulate. One day it may be possible to patch you up faster and more easily using glue made of nanoparticles, which can be injected through a needle for use in minimally invasive surgeries and eye surgery.

“In our previous work we’ve been developing tissue-adhesive glues and patches,” says Jeff Karp of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who is the senior author on a paper describing the glue in Advanced Healthcare Materials. “The challenge moving forward is: how do you deliver these materials?”

In order to inject the glue through a whisker-thin needle without clogging it, the researchers developed a way to make it in the form of nanoparticles, which solidified and formed a seal when a second chemical was injected. The glue can be delivered more quickly and with a smaller instrument than those needed to place sutures or staples, and its elastic properties better match those of the tissue around it. “It’s similar to a rubber band that you can stretch over and over again, except this is fully degradable,” says Karp.

Karp says the nanoparticle delivery mechanism could be adapted to other glues that have been developed recently to use in surgeries, including a cardiac glue his lab developed earlier. Though promising, none of these other glues have yet solved the delivery problem for minimally invasive surgery.

So far, the researchers have tested the glue in a cow eye and a living mouse’s ear. They plan to continue testing in rabbits and rats, and if successful, they will move to clinical testing in humans. They are also interested in developing different triggers to make the glue cure—different chemicals, light, or heat—so that it can be deployed exactly when and where a surgeon wants.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

What’s next for generative video

OpenAI's Sora has raised the bar for AI moviemaking. Here are four things to bear in mind as we wrap our heads around what's coming.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.