New Form of Memory Could Advance Brain-Inspired Computers

A new form of computer memory might help machines match the capabilities of the human brain when it comes to tasks such as interpreting images or video footage.

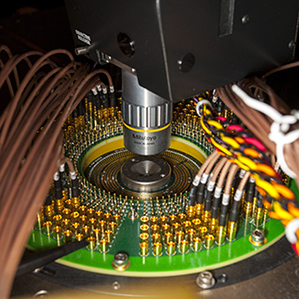

Researchers at IBM used what’s known as phase-change memory to build a device that processes data in a way inspired by the workings of a biological brain. Using a prototype phase-change memory chip, the researchers configured the system to act like a network of 913 neurons with 165,000 connections, or synapses, between them. The strength of those connections change as the chip processes incoming data, altering how the virtual neurons influence one another. By exploiting that property, the researchers got the system to learn to recognize handwritten numbers.

Phase-change memory is expected to hit the market in the next few years. It can write information more quickly, and pack it more densely, than the memory used in computers today (see “A Preview of Future Disk Drives”). A phase-change memory chip consists of a grid of “cells” that can each switch between two states to represent a digital bit of information—a 1 or a 0. In IBM’s experimental system, each “synapse” is represented by a pair of memory cells working together.

Computer scientists have been working for some time on chips that crudely mimic neurons and synapses. Such “neuromorphic” designs are radically different from the chips we use today. But they promise to make computers that are efficient at tasks computers normally find challenging, such as learning from experience or understanding video (see “Thinking in Silicon”).

Earlier this year, IBM announced the most complex neuromorphic chip yet (see “IBM Chip Processes Data Similar to the Way Your Brain Does”). It was made using the techniques and components used to build smartphone processors.

The experimental system announced by IBM researchers this week is much less powerful than that chip. But the fact the new system’s 165,000 synapses are made using phase-change memory is significant, says Geoff Burr, a researcher at IBM’s Almaden Research Center in San Jose, California.

Phase-change memory is thought to be particularly well suited to neuromorphic computer systems because it stores data so densely, making it possible to create brain-inspired systems with many more synapses, says Burr. Phase-change memory is also simpler to reprogram. That makes it practical for building a neuromorphic system that is able to “learn” by adjusting its behavior as it is fed new data.

Previous efforts at using phase-change memory to build neuromorphic systems have been modest, with 100 synapses or less, says Burr. The new system, built with colleagues at IBM and Pohang University of Science and Technology, in Korea, is more than 1,000 times that size. A paper on their results was presented at the International Electron Devices Meeting in San Francisco earlier this month.

The team was able to make a much larger system because it developed techniques to measure and compensate for the natural variability in the performance of each unit of phase-change memory. Similar variability affects the conventional memory chips in our phones and computers today, but error-checking methods are more advanced for those devices.

After being shown 5,000 labelled images of handwritten digits from a standardized data set, the researchers’ chip could recognize handwritten digits it had never seen before with an accuracy of 82 percent. Burr says that a recent tweak to his team’s error compensation methods should allow accuracy to climb to close to 99 percent.

Eugenio Culurciello, a professor at Purdue University who works on neuromorphic chip designs, says phase-change memory could enhance neuromorphic designs in interesting ways. However, he notes that engineers are at the early stages of understanding how to create brain-style chips. “These things are still a bit exotic,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.