Using Crowdsourcing to Protect Your Privacy

One of the key recommendations in the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s recent consumer privacy report is that the mobile industry give people simple ways to opt out of tracking, and communicate the often substantial privacy threats associated with many smart-phone apps. But that’s a tall task, given the expanding universe of more than a million apps—many of which can grab personal information such as the user’s location, phone number, and contacts list. Even when given a chance to review these settings in apps, most people don’t bother—they just click their assent, research has shown.

Now researchers at Carnegie Mellon and Rutgers University are finding it is possible to effectively outsource this screening task and then give consumers intuitive warnings about dubious data-access settings. The prototype system, built for Android apps for now, sends the app’s description—and its associated data-access requests—to human workers through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing service.

Those remote workers read the settings and offer opinions—a process that takes them less than a minute and for which they are paid 12 cents apiece. Their opinions can then be aggregated into warnings.

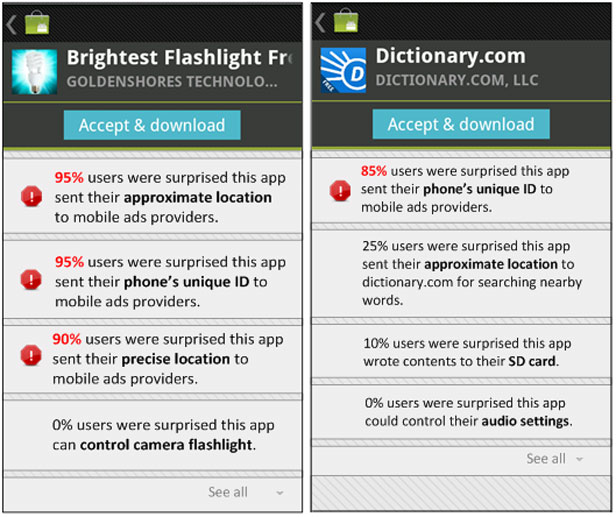

Consider the “Brightest Flashlight” app, from Goldenshores Technology. This app merely creates a white screen to provide illumination, but the app’s permission screen requires you to allow the app to furnish your “approximate location” to advertisers. It can also see your precise GPS position, and asks for your phone’s unique identifier number.

When the CMU and Rutgers researchers had 170 Mechanical Turk workers read the settings on Brightest Flashlight, between 90 and 95 percent of them were surprised by these requirements. A prototype warning screen delivers their findings—complete with red flag icons. “The basic idea here is: How do you help people who are not experts in network and computer security understand what an app is doing?” says Jason Hong, a CMU computer scientist who is one of the leaders of the project. “You are outsourcing people to read privacy settings and tell you what is interesting about it.”

The “crowds” behind Mechanical Turk tend to come to the same kinds of general conclusions about questionable privacy settings as computer scientists do, says Hong. The researchers are now studying whether people will avoid downloading apps after receiving such warnings, and hope to have a commercial app that provides crowdsourced opinions on privacy settings by the end of this year. It’s one of many ways that crowdsourcing in general is becoming a promising avenue for improving mobile security, says Landon Cox, a computer scientist at Duke University and codeveloper of an app privacy monitoring tool that tracks how Android apps use sensitive information.

Although the CMU-Rutgers research prototype is built for Android, which has 450,000 apps, the system theoretically could complement existing services, including Apple’s, that screen apps for known malicious software. This crowdsourced system might warn people about apps that may not technically be malware but are still not privacy friendly, says Janne Lindqvist, a Rutgers University researcher professor who is one of the project leaders.

The project has larger ambitions, too: to understand what apps are actually doing once installed and solicit crowd opinions on those aspects. The researchers have a program in development, code-named Squiddy, that examines apps, screen by screen, to see what data they access and what remote servers they contact. A companion program, code-named Gort, then presents this as an intuitive infographic describing these behaviors to crowdsourcers. (A paper describing the work is still under review.) Lindqvist says the cost of the service could be covered by the fees already extracted from app developers for publishing an app.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

What’s next for generative video

OpenAI's Sora has raised the bar for AI moviemaking. Here are four things to bear in mind as we wrap our heads around what's coming.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.