Why China is betting big on chiplets

By connecting several less-advanced chips into one, Chinese companies could circumvent the sanctions set by the US government.

For the past couple of years, US sanctions have had the Chinese semiconductor industry locked in a stranglehold. While Chinese companies can still manufacture chips for today’s uses, they are not allowed to import certain chipmaking technologies, making it almost impossible for them to produce more advanced products.

There is a workaround, however. A relatively new technology known as chiplets is now offering China a way to circumvent these export bans, build a degree of self-reliance, and keep pace with other countries, particularly the US.

In the past year, both the Chinese government and venture capitalists have been focused on propping up the domestic chiplet industry. Academic researchers are being incentivized to solve the cutting-edge issues involved in chiplet manufacturing, while some chiplet startups, like Polar Bear Tech, have already produced their first products.

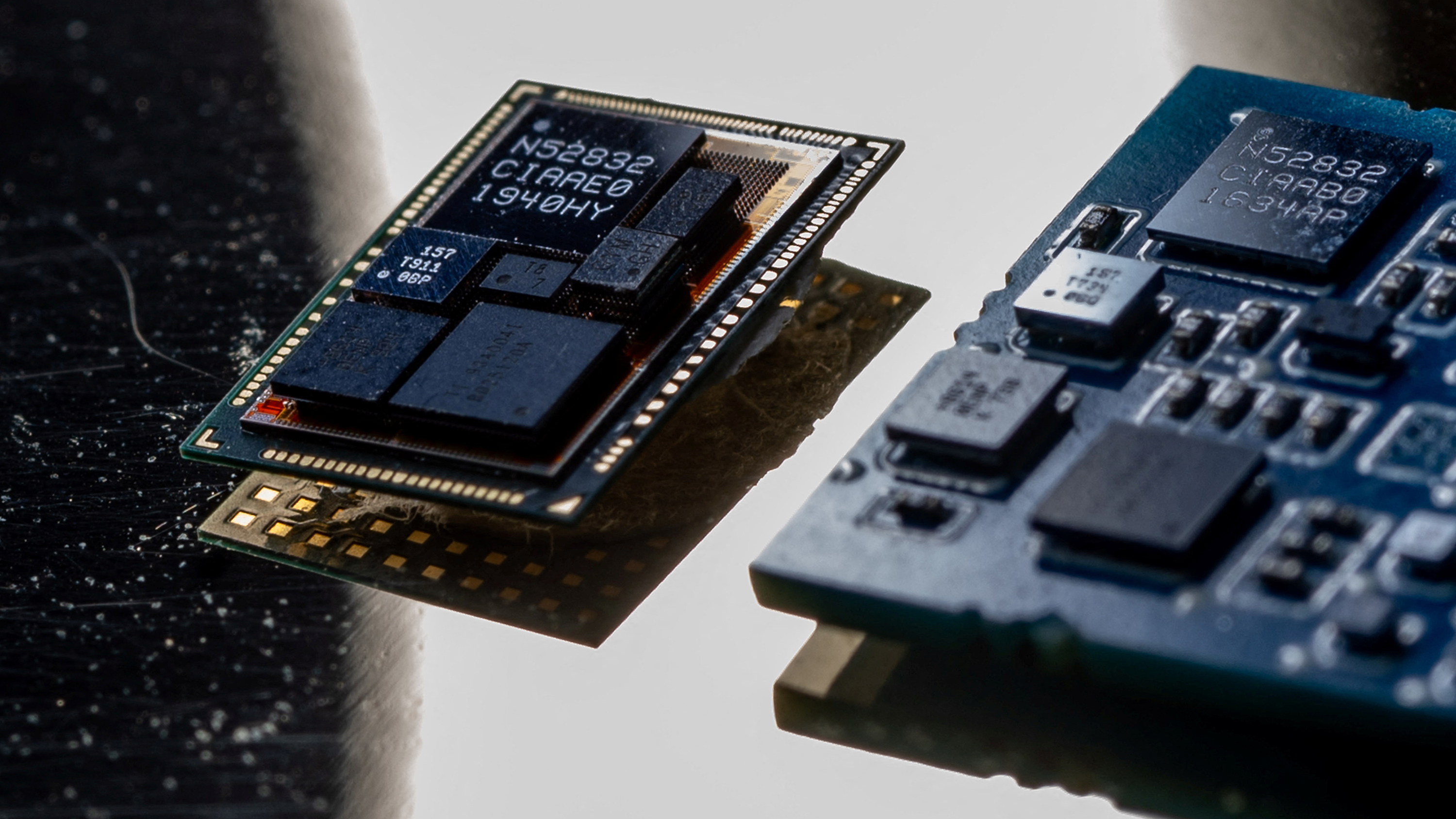

In contrast to traditional chips, which integrate all components on a single piece of silicon, chiplets take a modular approach. Each chiplet has a dedicated function, like data processing or storage; they are then connected to become one system. Since each chiplet is smaller and more specialized, it’s cheaper to manufacture and less likely to malfunction. At the same time, individual chiplets in a system can be swapped out for newer, better versions to improve performance, while other functional components stay the same.

Because of their potential to support continued growth in the post–Moore’s Law era, MIT Technology Review chose chiplets as one of the 10 Breakthrough Technologies of 2024. Powerful companies in the chip sector, like AMD, Intel, and Apple, have already used the technology in their products.

For those companies, chiplets are one of several ways that the semiconductor industry could keep increasing the computing power of chips despite their physical limits. But for Chinese chip companies, they could reduce the time and costs needed to develop more powerful chips domestically and supply growing, vital technology sectors like AI. And to turn that potential into reality, these companies need to invest in the chip-packaging technologies that connect chiplets into one device.

“Developing the kinds of advanced packaging technologies required to leverage chiplet design is undoubtedly on China’s to-do list,” says Cameron McKnight-MacNeil, a process analyst at the semiconductor intelligence firm TechInsights. “China is known to have some of the fundamental underlying technologies for chiplet deployment.”

A shortcut to higher-performance chips

The US government has used export blacklists to restrict China’s semiconductor industry development for several years. One such sanction, imposed in October 2022, banned selling to China any technology that can be used to build 14-nanometer-generation chips (a relatively advanced but not cutting-edge class) as well as more advanced ones.

For years, the Chinese government has looked for ways to overcome the resulting bottleneck in chipmaking, but breakthroughs in areas like lithography—the process of using light to transfer a design pattern onto the silicon base material—could take decades to pull off. Today, China still lags in chip-manufacturing capability relative to companies in Taiwan, the Netherlands, and elsewhere. “Although we’ve now seen [China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation] produce seven-nanometer chips, we suspect that production is expensive and low yield,” says McKnight-MacNeil.

Chiplet technology, however, promises a way to get around the restriction. By separating the functions of a chip into multiple chiplet modules, it reduces the difficulty of making each individual part. If China can’t buy or make a single piece of a powerful chip, it could connect some less-advanced chiplets that it does have the ability to make. Together, they could potentially achieve a similar level of computing power to the chips that the US is blocking China from accessing, if not more.

But this approach to chipmaking poses a bigger challenge for another sector of the semiconductor industry: packaging, which is the process that assembles multiple components of a chip and tests the finished device’s performance. Making sure multiple chiplets can work together requires more sophisticated packaging techniques than those involved in a traditional single-piece chip. The technology used in this process is called advanced packaging.

This is an easier lift for China. Today, Chinese companies are already responsible for 38% of the chip packaging worldwide. Companies in Taiwan and Singapore still control the more advanced technologies, but it’s less difficult to catch up on this front.

“Packaging is less standardized, somewhat less automated. It relies a lot more on skilled technicians,” says Harish Krishnaswamy, a professor at Columbia University who studies telecommunications and chip design. And since labor cost is still significantly cheaper in China than in the West, “I don’t think it’ll take decades [for China to catch up],” he says.

Money is flowing into the chiplet industry

Like anything else in the semiconductor industry, developing chiplets costs money. But pushed by a sense of urgency to develop the domestic chip industry rapidly, the Chinese government and other investors have already started investing in chiplet researchers and startups.

In July 2023, the National Nature Science Foundation of China, the top state fund for fundamental research, announced its plan to fund 17 to 30 chiplet research projects involving design, manufacturing, packaging, and more. It plans to give out $4 million to $6.5 million of research funding in the next four years, the organization says, and the goal is to increase chip performance by “one to two magnitudes.”

This fund is more focused on academic research, but some local governments are also ready to invest in industrial opportunities in chiplets. Wuxi, a medium-sized city in eastern China, is positioning itself to be the hub of chiplet production—a “Chiplet Valley.” Last year, Wuxi’s government officials proposed establishing a $14 million fund to bring chiplet companies to the city, and it has already attracted a handful of domestic companies.

At the same time, a slew of Chinese startups that positioned themselves to work in the chiplet field have received venture backing.

Polar Bear Tech, a Chinese startup developing universal and specialized chiplets, received over $14 million in investment in 2023. It released its first chiplet-based AI chip, the “Qiming 930,” in February 2023. Several other startups, like Chiplego, Calculet, and Kiwimoore, have also received millions of dollars to make specialized chiplets for cars or multimodal artificial-intelligence models.

Challenges remain

There are trade-offs in opting for a chiplet approach. While it often lowers costs and improves customizability, having multiple components in a chip means more connections are needed. If one of them goes wrong, the whole chip can fail, so a high level of compatibility between modules is crucial. Connecting or stacking several chiplets also means that the system consumes more power and may heat up faster. That could undermine performance or even damage the chip itself.

To avoid those problems, different companies designing chiplets must adhere to the same protocols and technical standards. Globally, major companies came together in 2022 to propose Universal Chiplet Interconnect Express (UCIe), an open standard on how to connect chiplets.

But all players want more influence for themselves, so some Chinese entities have come up with their own chiplet standards. In fact, different research alliances have proposed at least two Chinese chiplet standards as alternatives to UCIe in 2023, and a third standard that came out in January 2024 zoomed in on data transmission instead of physical connections.

Without a universal standard recognized by everyone in the industry, chiplets won’t be able to achieve the level of customizability that the technology promises. And their downsides could make companies around the world go back to traditional one-piece chips.

For China, embracing chiplet technology won’t be enough to solve other problems, like the difficulty of obtaining or making lithography machines.

Combining several less-advanced chips might give a performance boost to China’s chip technologies and stand in for the advanced ones that it can’t access, but it won’t be able to produce a chip that’s far ahead of existing top-line products. And as the US government constantly updates and expands its semiconductor sanctions, the chiplet technologies could become subject to restrictions too.

In October 2023, when the US Commerce Department amended its earlier sanction on the Chinese semiconductor industry, it included some new language and a few mentions of chiplets. The amendment added new parameters determining what technology is banned from being sold to China, and some of those additions seem tailored to measuring how advanced chiplets are.

While chip factories around the world are not restricted from producing less-advanced chips for China, the Commerce Department’s document also asked them to assess whether these products could become a part of a more powerful integrated chip, putting more pressure on them to verify that their products don’t end up being a component in something that they would have been banned from exporting to China.

With all the practical and political obstacles, the development of chiplets will still take some time, no matter how much political will and investment is poured into the sector.

It may be a shortcut for the Chinese semiconductor industry to make stronger chips, but it won’t be the magic solution to the US-China technology war.

Correction: The story has been updated to clarify the classification of 14-nanometer chips.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.