Explainer: What “poll watching” really means

President Trump is trying to recruit an “army” of poll watchers for Election Day. As part of his ongoing disinformation campaign about election fraud, these aggressive appeals to his supporters are raising worries about voter intimidation—or worse.

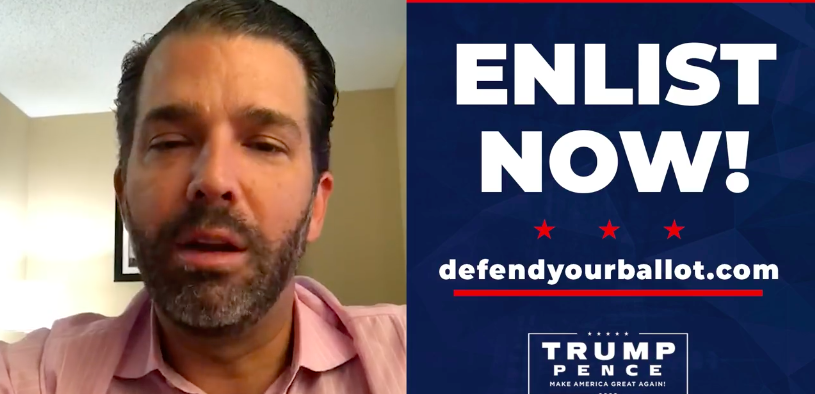

Meanwhile, Facebook just announced new rules that will no longer allow “militarized” language for poll watching on its platform. When asked about a video of Donald Trump Jr. calling for an “election security operation,” Facebook’s vice president of content policy, Monika Bickert, told reporters that “under the new policy if that video were to be posted again, we would indeed remove it.” (The original video is still online.)

But poll watching is a legitimate activity used by both parties and outside groups to monitor the vote. And every state has specific rules about what poll watchers can and cannot do.

What is a poll watcher?

A poll watcher’s job is to make sure every candidate has a fair chance of winning an election. In most states they are appointed, authorized, and trained, and must follow very specific rules. Typically they watch for any irregularities or violations of local election codes. If they spot an issue, they aren’t allowed to intervene directly with voters but must work with election officials.

What is Trump asking poll watchers to do?

Trump is arguing that Democrats are trying to steal the election with fraudulent votes, allegations that are not supported by any credible evidence. Amid the interruptions and insults of the first presidential debate last week, he talked repeatedly about intervention at polling places: “I’m urging my supporters to go into the polls and watch very carefully, because that’s what has to happen,” he said.

According to the instruction videos the Trump campaign has been distributing, they hope to challenge voter and ballot eligibility in some cases. Even that means, however, that Republican poll watchers should never be talking directly to the voters. In those cases, voters should be allowed a provisional ballot that will be counted once their status is verified. The same rules apply to Democratic watchers.

How can this go wrong?

“There are two ways in which the actions of these groups can be effective,” Charles Stewart of the MIT Election Lab told me. “One is by their actual physical presence. And the second one is by being worried about them.”

When the president tells the Proud Boys, a white supremacist organization, to “stand by” and calls his poll watchers an “army,” it implicitly creates the threat of violence on Election Day.

That perception itself could be enough to intimidate voters and lower turnout for groups who believe they’d be targeted.

“We know that Trump’s language has an effect on how his supporters behave,” says Nina Jankowicz, a disinformation researcher at the Wilson Center who has acted as an international election observer in Russia and Georgia.

“If you’re a Black or brown person listening to the debate, and you hear that Trump is encouraging his supporters to go and watch, and you’re in a place where it is permitted to open carry at a polling station, ask yourself: Do you bring your kids to vote with you that day? Probably not. Do you maybe not vote at all, or do you have to change your voting plan so that you are mitigating that risk? I think that is highly likely. The actual verbal threat is intimidation in my mind. It’s something that an international mission would note in its pre-election assessment heading into this consequential election here in the United States.”

Stewart suggested there may be less to worry about because groups like the Proud Boys often bark louder than they bite—and there aren’t as many of them as people think there are.

“Think about this Proud Boys rally that was supposed to be in Boston a couple of weeks ago,” he told me. “They had promised a crowd of 20,000 and 200 people showed up. There’s an over-promising and an overestimation about the ability of these groups to deploy to large numbers of polling places around the country.”

Is this a real concern?

The inability to muster numbers doesn’t mean there is no threat. In 1981, the Republican Party organized a “National Ballot Security Task Force” carrying guns, wearing uniforms, and preventing minority voters from casting ballots for New Jersey governor in multiple cities around the state. The whole effort took about 200 people, including off-duty police, and Republicans narrowly won that election. A lawsuit later banned Republicans from deploying armed poll watchers again—but that ban expired in 2017.

And then there is the potential for self-appointed poll watchers to cause trouble. Trump’s messages are at odds with how the law actually works, and could lead to questionable behavior from people who don’t know what an official poll watcher really does.

Dismissing the criticism, the Trump campaign’s deputy national press secretary, Thea McDonald, told me that “President Trump’s volunteer poll watchers will be trained to ensure all rules are applied equally, all valid ballots are counted, and all Democrat rule-breaking is called out.”

Yet Trump’s own Homeland Security analysts assessed white supremacists as the “most persistent and lethal threat in the homeland through 2021” and warned that “open-air, publicly accessible parts of physical election infrastructure” like polling places could be “flash points for potential violence.”

Are there protections?

For all the rising rhetoric, the law is clear, and voters should know they are protected from this kind of activity, which is already illegal across the United States. A new Brennan Center report details exactly how voter intimidation and discrimination are outlawed. Openly carrying guns in a polling place is illegal in most of the country.

Georgetown Law’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection is leading an effort to prevent private militias from operating near polling places or voter registration drives.

“It’s so important that elected officials and law enforcement make clear that there is no Second Amendment right to engage in paramilitary activity.”

“We think it’s so important that elected officials and law enforcement make clear that there is no Second Amendment right to engage in paramilitary activity and make clear that it is unlawful in every state,” says Georgetown’s Jonathan Backer.

“That’s so these groups will be discouraged from showing up and engaging in that sort of conduct, and so that voters can engage in the civic process without fear that these groups will show up and that elected officials won’t do anything to prevent it.”

Voters should not need to fear intimidation and violence on Election Day. Anyone experiencing problems should inform a poll worker, call the nonpartisan organization Protect the Vote, or in an emergency call 911.

What can you expect on Election Day?

The election is already under way, and for the most part, things are proceeding as planned. Poll watchers are a normal part of elections. Voter intimidation is not.

One key difference between today and 1981 is attention. Election officials and poll workers are actively looking for illegal intimidation near polls and increasingly speaking up to say they’ll prosecute attempts at voter intimidation.

It’s also useful to remember that even in 2016, voting rights groups were gearing up for problems extremely similar to the issues feared today. Those threats didn’t materialize. The issue is real, but it shouldn’t stop anyone from voting either in person or by mail. Voters are protected by law.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

How Wi-Fi sensing became usable tech

After a decade of obscurity, the technology is being used to track people’s movements.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.