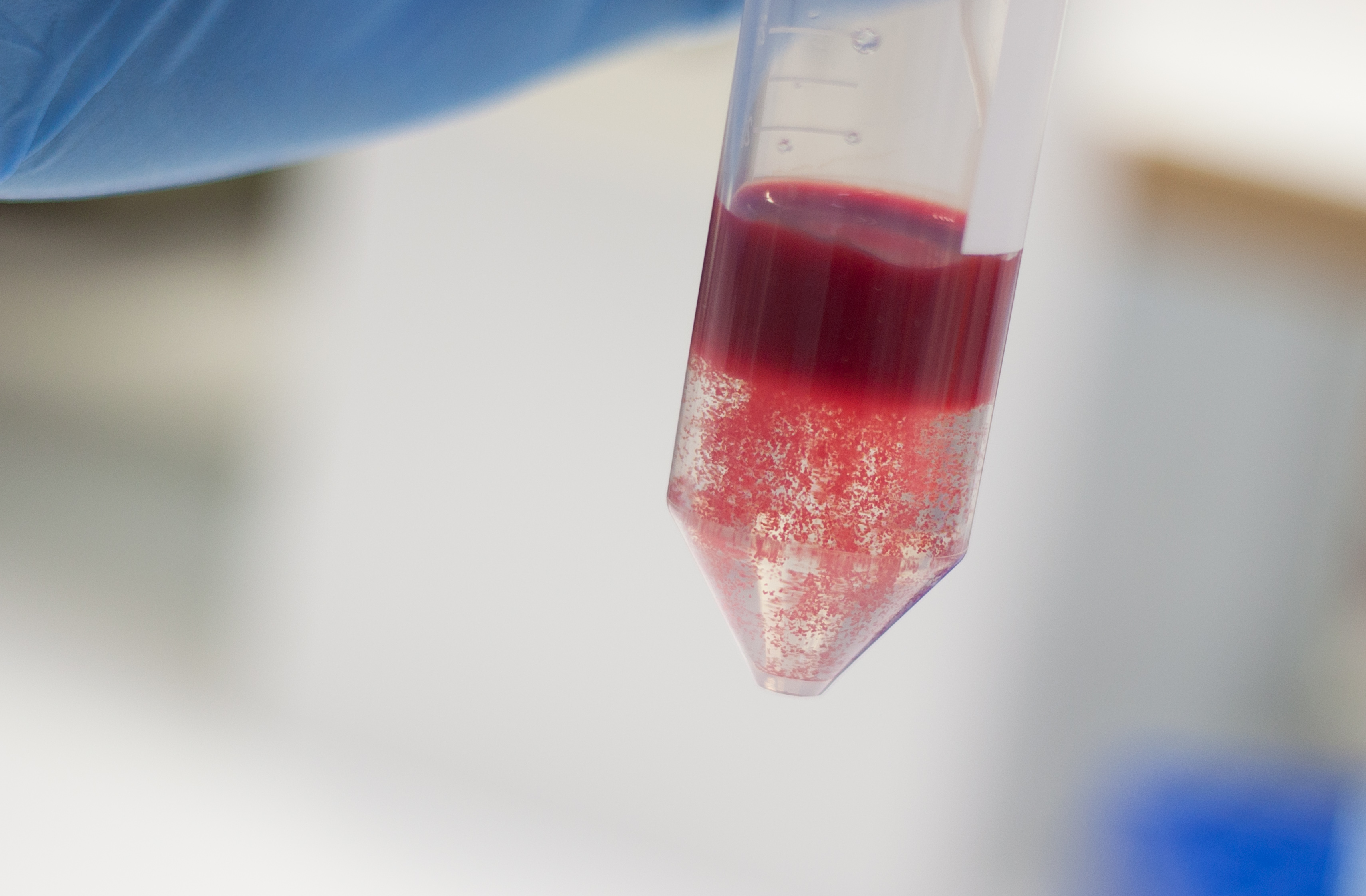

Is there a relationship between blood type and covid-19 infection?

This story is part of our ongoing list of answers to the biggest questions our readers have about the coronavirus. That list is constantly updated, and you can check it out here.

Since early in the pandemic, there’s been an interest in learning whether blood type has anything to do with who is more likely to get infected by the coronavirus or how bad the effects will be. Here’s what we know so far:

Early evidence: As far back as March, Chinese researchers analyzed blood types in 2,173 infected individuals from Wuhan and Shenzhen and compared those results with surveys of blood types from healthy populations in the same region. They found that 38% of the covid-19 patients had type A blood, compared with just 31% of the healthy people surveyed. By contrast, type O blood seemed to lead to a reduced risk, with 26% of the infected cases versus 34% of healthy people. And type A patients accounted for a larger proportion of covid-related deaths than any other blood type. Another study at Columbia University found similar trends: type A individuals were 34% more likely to test positive for the coronavirus, while those with type O or AB blood had a lower probability of testing positive.

The plot thickens: None of these studies were peer reviewed. But one that was, a genome study published in the New England Journal of Medicine on June 17, looked at genetic data from more than 1,600 hospitalized covid-19 patients in Italy and Spain, comparing their genes with those of 2,200 uninfected individuals. Those researchers found two gene variants in two regions of the genome associated with a bigger likelihood of severe covid-19 symptoms—including one region that determines blood type. Overall, patients with type A blood had a 45% higher risk of experiencing respiratory failure after contracting covid-19, while those with type O had a 35% reduction in risk.

Still, more recent studies throw some cold water on these notions. Researchers at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York and Massachusetts General Hospital each reviewed medical records of thousands of covid-19 patients. An initial batch of results from the former suggests Type A patients actually had a lower risk for being on a ventilator; while the latter (which is peer-reviewed) shows Type O patients were slightly less likely to get covid-19, and blood type overall had no significant effect on severity of illness or odds of death.

Reasons unknown: If blood type does have something to do with covid-19 risk, scientists don’t know yet what the causes would be. The authors of the NEJM study hypothesize that the proteins that define type A and B blood might affect the immune system’s production of antibodies, and perhaps these blood types have a slower immune response as a result. The genes that determine blood type might also have something to do with the ACE2 receptor that the coronavirus uses to infect human cells.

Skepticism: Besides the two hospital-run studies, there are methodological flaws to the early studies that have been run so far. The NEJM study, for example, used a control group that was composed primarily of blood donors—a group that is disproportionately higher in type O individuals than the general population (anyone can receive type O blood). And furthermore, blood types were inferred on the basis of genes and not through direct analysis of blood cells themselves, which isn’t quite as accurate.

In any case, blood type doesn’t seem to be among any of the more significant risk factors that distinguish mild cases from severe ones. The biggest factors are still age and underlying health issues. And type O individuals are not immune to severe infection.

This post has been updated.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.