This is what happens when you get the coronavirus

The epidemic of a novel coronavirus spreading from central China has sickened more than 43,000 people and killed more than 1,000, eclipsing the death toll from a related virus, SARS.

What happens when you get infected by the virus, and what are your chances if you do? A new report describing what happened to 138 patients treated in a hospital on the frontlines in Wuhan, China, has some answers—and some alarming news about how the virus can spread inside a hospital.

The Wuhan doctors, led by Zhiyong Peng at the critical care department at Zhognan Hospital of Wuhan University, say about 40% of the people they treated actually caught the infection at their hospital, including 40 health-care professionals and 17 patients who were already there for surgeries or other reasons.

They said 4.3% of the patients died and about 34% got better and left the hospital, while the rest were still being treated. Outside of China, the death rate appears to be much lower, but in Wuhan doctors are clearly struggling. The city has been under a lockdown quarantine since last month.

Early symptoms: The most common symptom of the coronavirus is a fever, which nearly everyone gets, followed by fatigue and dry cough. A few people also experienced diarrhea or nausea a day or two before any other symptoms.

Getting to the hospital: It took about seven days from first symptoms for people to check into the hospital, by which time many were having trouble breathing, say the Wuhan doctors. It wasn’t clear if their patients waited to seek help or were among those initially turned away in overcrowded conditions.

Confirming infection: The test for the virus is a throat swab, which is analyzed with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify its telltale genetic material.

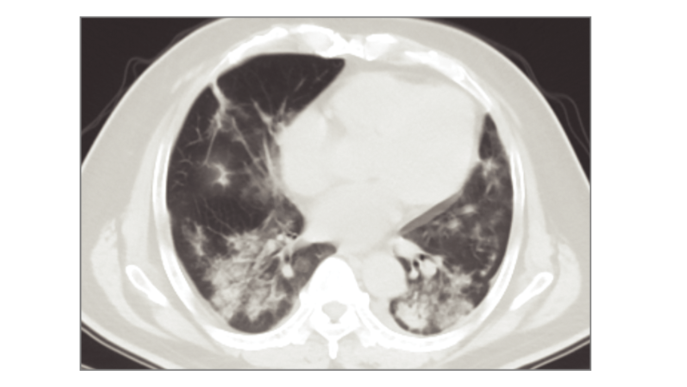

Chest scans: Some patients put through a CAT scanner showed spots of shadows in their lungs, what doctors call a “ground glass” appearance.

Getting to the ICU: The Chinese team said a quarter of their patients ended up in the intensive care unit, mostly because of acute respiratory distress syndrome, or “ARDS.” That’s when the lungs fill with fluid and lose the ability to carry oxygen. That can affect other organs, like the kidneys, and cause death. The chance of ending up in the ICU was higher for people who were already weak.

It affects older people more often: While older people tended to have more serious diseases, this hospital saw patients as young as 22 and as old as 92. The median age was 56.

The treatments: The report from China shows that doctors did not have a silver bullet to cure the infection. In Wuhan, most people got an antiviral drug called oseltamivir, which they say didn’t have a discernible effect. Several other drugs, including anti-HIV drugs, have also been tried elsewhere. Patients in the most trouble sometimes got oxygen therapy or were hooked up to a machine that pumps their blood and adds oxygen, saving their heart and lungs from doing the work.

More on coronavirus

Our most essential coverage of covid-19 is free, including:

How does the coronavirus work?

What are the potential treatments?

What's the right way to do social distancing?

Other frequently asked questions about coronavirus

---

Newsletter: Coronavirus Tech Report

Zoom show: Radio Corona

See also:

Please click here to subscribe and support our non-profit journalism.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.