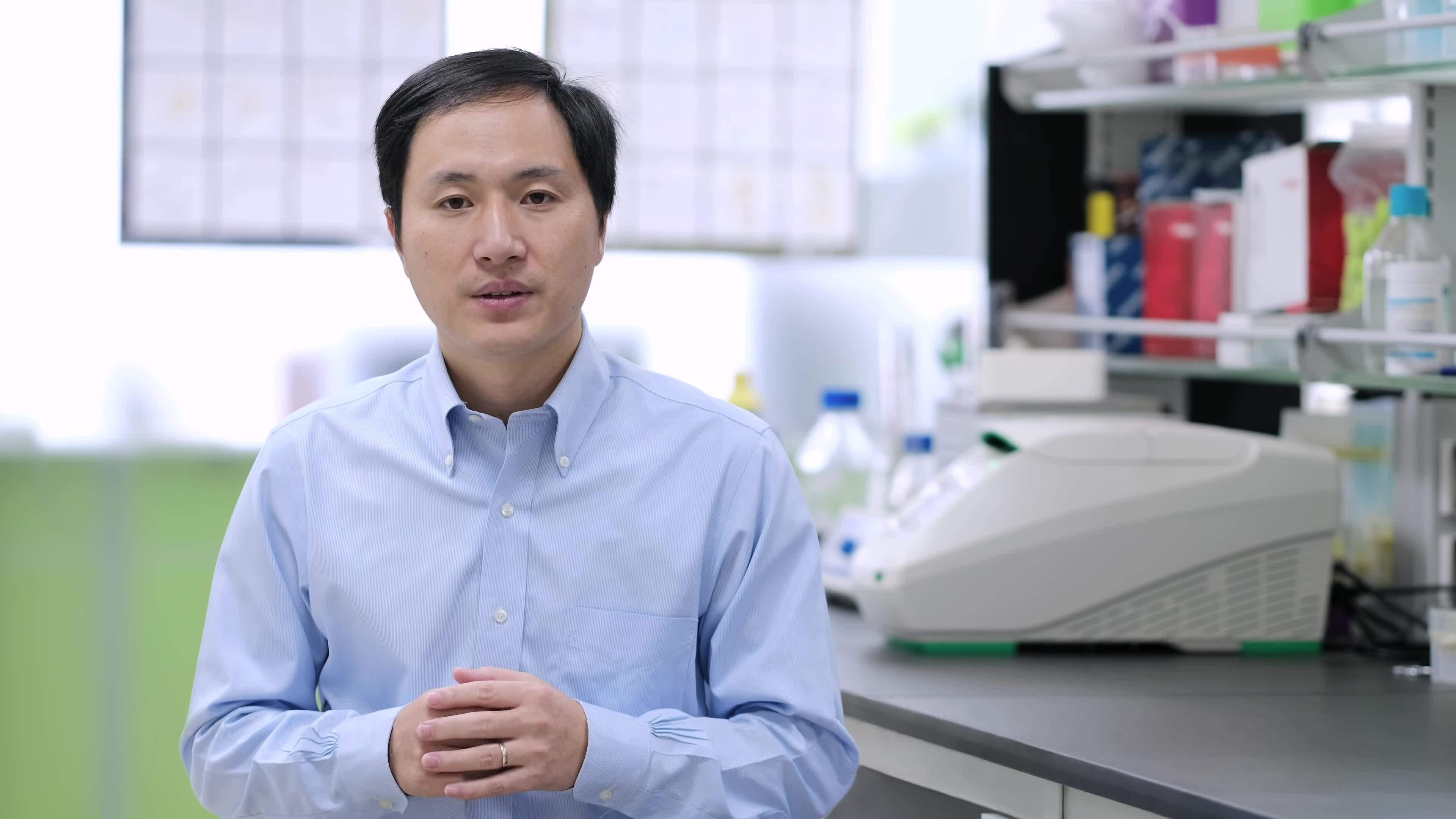

He Jiankui faces three years in prison for CRISPR babies

The Chinese scientist who created the world's first gene-edited children has been sentenced to three years in prison by a Chinese court.

He Jiankui, a biophysicist trained at Rice University and Stanford, shocked the world last year with his claim to have created genetically modified humans, twins referred to as Lulu and Nana.

In addition to a prison term, He will pay a $425,000 fine and will be banned for life from further involvement in reproductive medicine, according to a report from China's Xinhua news agency. The sentence was handed down December 30 by Shenzhen Nanshan District People's Court.

He's team employed the versatile DNA-editing technology known as CRISPR to alter the twins' genomes when they were newly fertilized embryos floating in a petri dish. The scientists then transferred them to a woman's uterus to begin the pregnancy.

Two of He's coworkers, Zhang Renli and Qin Jinzhou, will also receive prison terms of two years and 18 months, respectively, for "carrying out human embryo gene editing ... for reproductive purposes."

He's team was based at the Southern University of Science and Technology, and a draft scientific manuscript describing the creation of the twins lists a total of 10 authors, including lab workers and bioinformatics experts.

It's not clear if the other team members will face penalties.

Instead, in addition to He, the punishments announced in China appeared to single out those scientists directly responsible for injecting the gene-editing ingredients into human embryos, a procedure typically undertaken using an ultra-fine needle.

These include Qin, an embryologist listed as the first author on the draft manuscript, and Zhang, whose name appears on a separate unpublished paper detailing preliminary experiments, which describes him as having "performed the human embryo microinjections." Zhang at the time was affiliated with the Reproductive Medicine Center of the Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences/Guangdong General Hospital in Guangzhou.

According to the court, He and his research colleagues conspired beginning in 2016 to create gene-edited babies, settling on the idea of modifying a gene called CCR5, changes that could render humans resistant to HIV.

He believed his research could bring him fame and fortune and might be a major scientific coup for China, too. But after the existence of the experiment was disclosed by MIT Technology Review last November, most experts immediately condemned the research, and provincial authorities opened what they termed a criminal investigation.

The court's statement is the first time Chinese authorities have acknowledged the birth of a third gene-edited child in China, in addition to the twins. The second pregnancy likely came to term during the summer of 2019.

The court found that He and his colleagues "deliberately violated the relevant national regulations on scientific research and medical management" and "rashly applied gene editing technology to human assisted reproductive medicine."

During the trial, which was not public, investigators produced evidence including documents, witness accounts, electronic files, and videos. He reportedly pled guilty, as did his two associates.

According to the Xinhua news agency, He will be placed on a "black list" that will bar him, for life, from using assisted reproductive technology in humans.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.