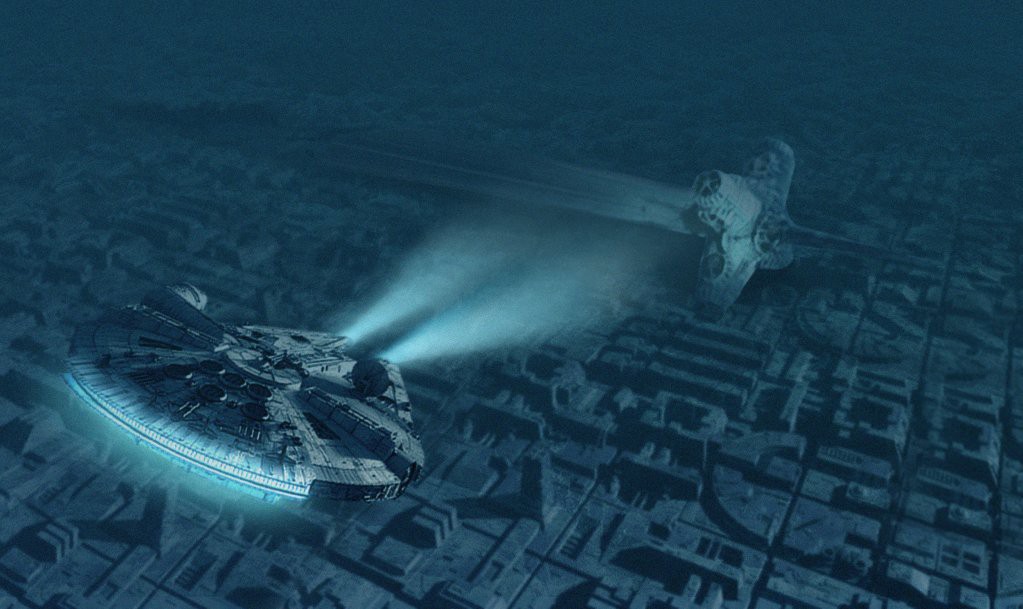

Are there any realistic spaceflight technologies from Star Wars?

Every week, the readers of our space newsletter, The Airlock, send in their questions for space reporter Neel V. Patel to answer. This week: the technology of Star Wars.

Reader question

There’s a new Star Wars trailer out this week, which got me thinking. George Lucas’s space opera is famously soft sci-fi—so divorced from any actual science that it’s pretty much just fantasy. But there must be some technology in the series that’s actually based on something real, so what’s the most realistic invention, gadget, or machine in the galaxy far far away? —Jack

Neel’s answer

Unfortunately, when it comes to space technology, Star Wars takes liberties to new extremes. There is practically nothing real about its depiction of spaceflight. In real life, getting a single rocket off the surface of Earth and into space takes an excruciating amount of power and effort. It’s a process where a zillion things could go wrong and lead to catastrophic failure. And ships don’t move like airplanes in the vacuum of space.

To be fair, there are some aspects presented in Star Wars (and other works of science fiction) that scientists and engineers want to make into reality. One of the best examples is the artificial gravity depicted inside these ships. The lack of gravity in space can cause a host of problems for human bodies, and artificial gravity could help mitigate these effects.

In Star Wars, whether it’s on a space station as giant as the Death Star or inside a craft as small as an X-wing, the artificial gravity is just there, like some kind of ether. It makes no sense.

Still, many experts think we could simulate gravity in space by generating a high amount of centripetal force, à la 2001: A Space Odyssey. The closest humans have ever come to producing this effect was during NASA’s Gemini 8 mission in 1966, and this was only because an accident induced a high acceleration that forced the mission to terminate early. Later that year, Gemini 11 attempted to produce artificial gravity through rotation. The effect was too small to be felt by the astronauts onboard, although small objects were seen falling toward the end of the capsule.

While artificial gravity is not a high priority right now for anybody, experts continue to pitch new proposals for studying its implementation. We’re likely to see them taken more seriously as we pursue more long-duration missions. The general idea that you could simulate terrestrial gravity in a spacecraft is not unthinkable. It just requires a lot of smart engineering and the type of money and resources that exceed some countries’ annual GDPs.

To see our reader questions first, make sure you sign up for The Airlock here. It’s free—and it’s sent out every Wednesday.

Deep Dive

Space

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

The great commercial takeover of low Earth orbit

Axiom Space and other companies are betting they can build private structures to replace the International Space Station.

The race to fix space-weather forecasting before next big solar storm hits

Solar activity can knock satellites off track, raising the risk of collisions. Scientists are hoping improved atmospheric models will help.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.