Controlling Diabetes with a Skin Patch

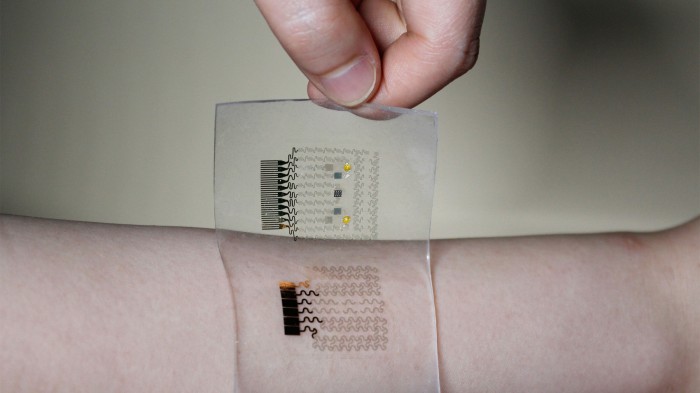

Attempting to free people with diabetes from frequent finger-pricks and drug injections, researchers have created an electronic skin patch that senses excess glucose in sweat and automatically administers drugs by heating up microneedles that penetrate the skin.

The prototype was developed by Dae-Hyeong Kim, assistant professor at Seoul National University and researchers at MC10, a flexible-electronics company in Lexington, Massachusetts. Two years ago the same group prototyped a patch aimed at Parkinson’s patients that diagnoses tremors and delivers drugs stored inside nanoparticles.

Other efforts to develop minimally invasive glucose monitoring have used ultrasound and optical measurements to detect glucose levels. And a variety of skin patches could deliver insulin or metformin, a popular drug used to treat type 2 diabetes. But the new prototype incorporates both detection and drug delivery in one device.

The patch, described in a paper in Nature Nanotechnology, is made of graphene studded with gold particles and contains sensors that detect humidity, glucose, pH, and temperature. The enzyme-based glucose sensor takes into account pH and temperature to improve the accuracy of the glucose measurements taken from sweat.

If the patch senses high glucose levels, heaters trigger microneedles to dissolve a coating and release the drug metformin just below the skin surface. “This is the first closed-loop epidermal system that has both monitoring and the noninvasive delivery of diabetes drugs directly to the subject,” says Roozbeh Ghaffari, cofounder of MC10.

The only minimally invasive technology for monitoring blood glucose ever approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was a gadget called the GlucoWatch Biographer, which used an electrical current to extract fluids from beneath the skin. It was approved in 2001, but patients complained of discomfort and sores, and the device was pulled from the market in 2007.

Other researchers are using different approaches to help people with diabetes. A device recently prototyped at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, consists of a fingernail-size patch with more than 100 microneedles that contain tiny sacs full of insulin and an enzyme. Glucose in the blood permeates the sac. The enzyme converts the glucose into an acid that opens the sac to release insulin as the needles prick the skin.

That approach would deliver insulin when needed. But the MC10 device, as an electronic platform, could also store data on drug delivery activity and transmit it to a wearable device that could then wirelessly transmit it to a smartphone.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.