How a Wiki Is Keeping Direct-to-Consumer Genetics Alive

When Meg DeBoe decided to tap her Christmas fund to order a $99 consumer DNA test from 23andMe last year, she was disappointed: it arrived with no information on what her genes said about her chance of developing Alzheimer’s and heart disease. The report only delved into her genetic genealogy, possible relatives, and ethnic roots.

That’s because just a month earlier, in November 2013, the Food and Drug Administration had cracked down on 23andMe. The direct-to-consumer gene testing company’s popular DNA health reports and slick TV ads were illegal, it said, since they’d never been cleared by the agency.

But DeBoe, a mommy blogger and author of children’s books, found a way to get the health information she wanted anyway. Using a low-budget Web service called Promethease, she paid $5 to upload her raw 23andMe data. Within a few minutes she was looking into a report with entries dividing her genes into “Bad news” and “Good news.”

As tens of thousands of others seek similar information about their genetic disposition, they are loading their DNA data into several little-known websites like Promethease that have become, by default, the largest purveyors of consumer genetic health services in the United States—and the next possible targets for nervous regulators.

After the FDA crackdown, consumers are trading information on where to learn about their genes. “Don’t let the man stop you,” said one.

Promethease was created by a tiny, two-man company run as a side project by Greg Lennon, a geneticist based in Maryland, and Mike Cariaso, a computer programmer. It works by comparing a person’s DNA data with entries in SNPedia, a sprawling public wiki on human genetics that the pair created eight years ago and run with the help of a few dozen volunteer editors. Lennon says Promethease is being used to build as many as 500 gene reports a day.

Many people are arriving directly from 23andMe. After its health reports were blocked, consumers complained angrily about the FDA on the company’s Facebook page, where they also uploaded links to the Promethease website, calling it a “workaround,” a way to get “exhaustive medical info” in reports that are “similar, but not as pretty.” The mood was one of civil disobedience. “Don’t let the man stop you from getting genotyped,” wrote one.

The FDA is being cautious with personal genomics because although DNA data is easy to gather, its medical meaning is less certain.

Consumer DNA tests determine which common versions of the 23,000 human genes make up your individual genotype. As science links these variants to disease risk, the idea has been that genotypes could predict your chance of getting cancer or heart disease, or losing your eyesight. But predicting risk is tricky. Most genes don’t say anything decisive about you. And if they do, you might well wish for a doctor at your side when you find out. “I don’t believe that this kind of risk assessment is mature enough to be a consumer product yet,” says David Mittelman, chief scientific officer of Gene by Gene, a genetic laboratory that performs tests.

In barring 23andMe’s health reports, the FDA also cited the danger that erroneous interpretations of gene data could lead someone to seek out unnecessary surgery or take a drug overdose. Critics of the decision said it had more to do with questions about whether consumers should have the right to get genetic facts without going through a doctor. “It’s an almost philosophical issue about how medicine is going to be delivered,” says Stuart Kim, a professor at Stanford University who helped developed a DNA interpretation site called Interpretome as part of a class he teaches on genetics. “Is it going to be concentrated by medical associations, or out there on the Internet so people can interact?”

Now a question is whether Promethease and sites like it could, or should, be the next target of regulators. Lennon believes his service is outside the FDA’s reach, because it doesn’t offer a spit kit or perform DNA tests itself but instead operates like a “literature retrieval service,” presenting a version of what’s in the science journals. Regulate us, says Lennon, and you’d have to shut down WebMD and Wikipedia, too.

Reached by MIT Technology Review, the FDA said it has authority to regulate software that interprets genomes, even if such services are given away free. The agency does not comment on specific companies.

“We know that they know about us,” says Lennon. “They have not knocked on our door. We don’t know if they will come knocking tomorrow.”

Gene Results

Promethease can reanalyze the results of genotype tests sold legally for $99 to $199 by a variety of genealogy companies, including 23andMe, Ancestry.com, and National Geographic’s human ancestry project. Several other “interpretation-only” websites, including Interpretome, LiveWello, and Genetic Genie, also analyze the results of these tests, which are provided to customers as a text file containing a list of genetic variations.

To Barbara Evans, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center, the idea that people can gather DNA from one company and analyze it elsewhere is a significant legal development. Previously, the same lab that tested you would be the one to tell you what the results meant. But DNA information is essentially digital. That means it can plug and play anywhere. “It’s going to be quite difficult to regulate,” Evans predicts. She believes that services like Promethease could invoke free-speech arguments and other legal defenses if regulators ever approached them.

“It’s not reasonable to think there’s some specific date—May 18, 2035—that the genome will all make sense, and that’s the day you are allowed to see it.”

MIT Technology Review tested several interpretation-only sites using DNA data of anonymous donors posted publicly by the Personal Genome Project, a data-sharing initiative started by Harvard Medical School. All the sites quickly reported gene variants contained in the files, although the number of variants reported varied, from as few as 35 to as many as 17,667 for Promethease. Some of the reports were also more detailed than others.

Two of the sites appeared designed to steer users toward alternative medicine. Genetic Genie, a free service that carries ads for vitamins, reported the fewest genes in what it called a “detoxification profile.” LiveWello charged $19.95 and included more genes, as well as links to scientific reports. That site, however, directed users to get an “explanation” of the results by contacting chiropractors, dieticians, and mind-body healers whose telephone numbers it provided.

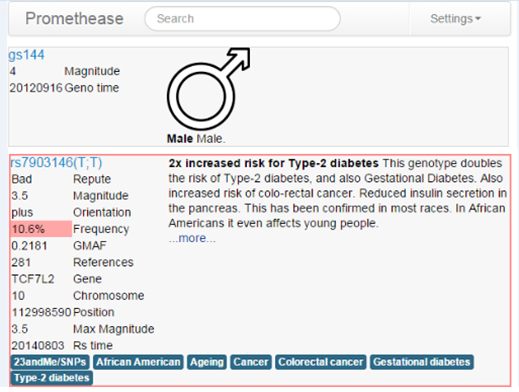

The Promethease report was the most detailed, although its clunky, bare-bones design is not easy to use. It organizes a person’s genetic variations under categories such as “medical conditions” and “medicines.” Users can then click to see information about individual genes that scientific research has suggested could raise, or lower, their risk for drug reactions, common diseases, or personality traits such as a lack of empathy.

The information in the report is similar to that in 23andMe’s banned “Personal Genome Service,” but there are differences. Promethease makes little effort to combine the genetic risks for any one disease into a single comprehensible number. That makes the report more like a jumble of facts than a diagnosis. Lennon says this is intentional. He says 23andMe stepped on shaky scientific ground by trying to merge risks into one neat score.

“Everyone wants to sell a simple answer: ‘Here is your risk.’ But we don’t know how these things interact,” he says. At the same time, he believes the uncertain value of DNA information is not a reason to keep it away from lay people. “It’s not reasonable to think there’s some specific date—May 18, 2035—that the genome will all make sense, and that’s the day you are allowed to see it,” he says.

For now, consumers have to fend for themselves in a thicket of scientific information—and make their own decisions about risks. To DeBoe, the blogger, this meant bringing some “perspective and common sense” to the report she purchased from Promethease. It told her that her versions of 11 genes carried some increased risk of breast cancer, and one lowered it. But she wasn’t alarmed, because it turns out that’s not really unusual. “It’s not a crystal ball. I think a lot of people make that mistake,” she says. “That said, I did go into it wanting to know a few specific things: if I had a high risk [or] genetic predisposition toward heart disease, diabetes, or Alzheimer’s. I don’t, which was relieving.”

Determining whether her relief is really justified might require the help of a trained geneticist. At least that’s the current view of the FDA and medical societies. But DeBoe did take the report to her doctor. It said she had a gene for caffeine sensitivity, and DeBoe says her doctor agreed she should stick to decaf and avoid drugs like Novocain. “I think that’s how people should be using this—as a conversation-starter with medical professionals,” she says.

Under the Radar

To Lennon and Cariaso, the surge of interest in Promethease and SNPedia represents a triumph for a no-frills approach to genetics. In 2006, the same year 23andMe was founded, they launched SNPedia as a site that would let them—and anyone else—keep tabs on what science was learning about each gene variant. Lennon says the site was modeled on Wikipedia. “That was the promise of the genome, that it should be for everybody,” he says.

These days, SNPedia keeps tabs on about 57,000 gene variants (known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs) with the help of a few dozen volunteers. One frequent contributor is James Lick, an entrepreneur who owns two Subway sandwich franchises in Taipei. Lick, who is adopted, says he became interested in genetics while searching for his birth parents and now spends a few hours a week updating SNPedia. Last month, he created a new listing for a gene called NGLY1, adding a link to a New Yorker article that discussed the gene and its role in a rare childhood disease. Unlike the government-run dbSNP, which tracks millions of variations whether or not anything is known about them, SNPedia focuses on variations that have known effects on a person. “It’s not everything—just what’s interesting and where someone goes through the bother to create a page,” says Lick.

Consumers have to fend for themselves in a thicket of scientific information—and make their own decisions about risks.

The effort has been low-key; SNPedia is mostly a place for what Cariaso calls “recreational genomics.” Lennon, who had soured on venture capital, also didn’t want investors involved. As a result, their work was overshadowed by 23andMe, which raised $126 million and hired more than a dozen PhD geneticists to curate its own gene lists. Its CEO, Anne Wojcicki, who is married to Google cofounder Sergey Brin, landed on magazine covers, and a board member predicted that her startup would “become the Google of personalized healthcare.”

It didn’t happen that way. And following the FDA’s action to block 23andMe’s reports, traffic to interpretation-only sites jumped. Interpretome, maintained by Konrad Karczewski, a postdoctoral researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, now has 80 to 100 visitors per day, twice as many as last year. Even more are heading to Promethease. Lennon says the site averages between 50 and 500 reports per day, including a free version and a faster-running paid product. He won’t get too specific about the numbers or say how much money Promethease is earning. “We are somewhat shy about saying how much business we are doing,” he says.

That could be out of a desire not to rouse regulators. The FDA has wide discretion to act but often chooses to ignore small-time operators that bend the rules, especially if they avoid making overt health claims. But Cariaso and Lennon can’t say they didn’t anticipate trouble. After all, they named their software after Prometheus, the titan who defied the gods by stealing fire from Mt. Olympus and giving it to mankind. (According to myth, he was later punished and chained to a rock for eternity.)

“Fire is knowledge of your own DNA,” says Cariaso. “The gods are anyone who would try to prevent me from knowing about myself.”

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.