The $1 Origami Microscope

Origami, the Japanese art of paper folding, has evolved considerably since it appeared in the western world over a century ago. Folding is simple, easy and cheap. So it’s no wonder that scientists and engineers have begun to exploit it in all kinds of innovative ways. They now use origami to construct everything from molecular machines to space telescopes.

Today, Manu Prakash and pals at Stanford University in California, reveal how they’ve designed and built an origami microscope that is constructed largely out of folded paper and costs less than a dollar to make. And they say their device could revolutionize the way billions of people see the world around them.

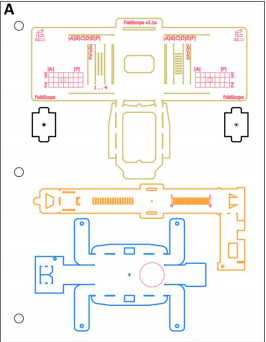

Prakash and co call their device the Foldscope and say it can be assembled from a flat sheet of paper in under 10 minutes.

“Although it costs less than a dollar in parts, it can provide over 2,000X magnification with submicron resolution, weighs less than two nickels, is small enough to fit in a pocket, requires no external power, and can survive being dropped from a 3-story building or stepped on by a person,” they add.

As well as the paper structure, the device also requires a tiny lens (cost $0.56), and to provide light, a 3V button battery (cost $0.06), an LED ($0.21) plus a couple of other bits and pieces, such as tape and a switch. The total cost is $0.97, say Prakash and co.

The device is simple to operate. Simply place your eye close enough to the lens that your eyebrow touches the paper and then focus and pan using your thumbs to manipulate the position of the lens and its distance to the subject.

And the results are impressive. Prakash and co show how to use the device in a number of different configurations to achieve brightfield and darkfield images as well as fluorescence microscopy.

That has important applications. One obvious use is in education, where such cheap devices could bring microscopy to the masses.

But equally important are applications in healthcare where foldable microscopes could be made disease specific with the right kind of staining and filters. Prakash and co have already shown how their device can image common bacteria and parasites such as Giardia lamblia, Leishmania donovani, Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas parasite), Escherichia coli and so on.

And at a dollar a throw, these microscopes could be made disposable to reduce cross contamination and the possibility of infection from highly contagious diseases.

These guys have big plans for the future. They say that modern manufacturing techniques would allow the production of these devices on a huge scale. “Roll-to-roll processing of flat components and automated “print-and-fold” assembly make yearly outputs of a billion units attainable,” they say.

And the Foldscope could be made substantially better. A particular focus (ahem) will be to improve the lenses with modern manufacturing techniques, perhaps making them aspheric to reduce optical aberrations.

Prakash and co are clearly on a mission. Prakash already talked about the Foldscope at TED and received wide media coverage.

But in a sense that’s the easy part. Nobody should underestimate the logistical, economic and political problems in distributing anything on a global scale, particularly in the developing world.

That’s something the One Laptop Per Child team have some experience with. Perhaps there’s a potential partnership there. Either way, we wish them luck.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1403.1211: Foldscope: Origami-Based Paper Microscope

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

How Wi-Fi sensing became usable tech

After a decade of obscurity, the technology is being used to track people’s movements.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.