Digital Imaging, Reimagined

Richard Baraniuk and Kevin Kelly have a new vision for digital imaging: they believe an overhaul of both hardware and software could make cameras smaller and faster and let them take incredibly high-resolution pictures.

Today’s digital cameras closely mimic film cameras, which makes them grossly inefficient. When a standard four-megapixel digital camera snaps a shot, each of its four million image sensors characterizes the light striking it with a single number; together, the numbers describe a picture. Then the camera’s onboard computer compresses the picture, throwing out most of those numbers. This process needlessly chews through the camera’s battery.

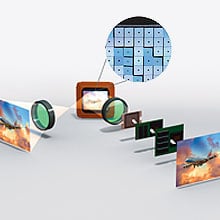

Baraniuk and Kelly, both professors of electrical and computer engineering at Rice University, have developed a camera that doesn’t need to compress images. Instead, it uses a single image sensor to collect just enough information to let a novel algorithm reconstruct a high-resolution image.

At the heart of this camera is a new technique called compressive sensing. A camera using the technique needs only a small percentage of the data that today’s digital cameras must collect in order to build a comparable picture. Baraniuk and Kelly’s algorithm turns visual data into a handful of numbers that it randomly inserts into a giant grid. There are just enough numbers to enable the algorithm to fill in the blanks, as we do when we solve a Sudoku puzzle. When the computer solves this puzzle, it has effectively re-created the complete picture from incomplete information.

Compressive sensing began as a mathematical theory whose first proofs were published in 2004; the Rice group has produced an advanced demonstration in a relatively short time, says Dave Brady of Duke University. “They’ve really pushed the applications of the theory,” he says.

Kelly suspects that we could see the first practical applications of compressive sensing within two years, in MRI systems that capture images up to 10 times as quickly as today’s scanners do. In five to ten years, he says, the technology could find its way into consumer products, allowing tiny mobile-phone cameras to produce high-quality, poster-size images. As our world becomes increasingly digital, compressive sensing is set to improve virtually any imaging system, providing an efficient and elegant way to get the picture.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.