This Picasso painting had never been seen before. Until a neural network painted it.

The Old Guitarist is probably the most famous painting from Picasso’s Blue Period. It dates from 1903-1904, when the young artist was living in poverty in Paris. Picasso used the color blue to represent the emotional pain and desolation he was experiencing at the time.

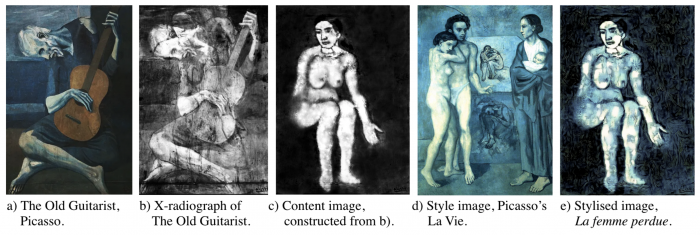

But The Old Guitarist is interesting for another reason. Art historians have long noted the presence of a ghostly woman’s face faintly visible beneath the paint. In 1998, conservators at the Art Institute of Chicago, where the painting hangs, photographed it using x-rays and infrared light to see what lies beneath the surface.

These images show an entirely different painting. It depicts a seated woman holding out her left arm. The researchers then matched this painting to a composition Picasso had sketched out in a letter to a colleague at the time.

The findings fascinated the art world. Artists often paint over earlier works, particularly during periods of penury when canvas is in short supply.

The new image provided an important insight into the progression of Picasso’s work, his subjects, and his thinking during his Blue Period. Since he is perhaps the most important artist of 20th century, that’s hugely significant.

But from an aesthetic point of view, what the researchers managed to retrieve is disappointing. Infrared and x-ray images show only the faintest outlines, and while they can be used to infer the amount of paint the artist used, they do not show color or style. So a way to reconstruct the lost painting more realistically would be of huge interest.

Anthony Bourached and George Cann at University College London have used a machine vision technique called neural style transfer to retrieve the lost Picasso painting in color for the first time. Their approach allows the painting to be seen as part of the artist’s Blue Period.

The researchers have used the same technique to retrieve lost paintings by other artists and say it has the potential to transform the way art historians work.

First some background. Neural style transfer was developed in 2015 by Leon Gatys and colleagues at the University of Tubingen in Germany. It comes about from a fascinating insight into the way neural networks learn to recognize images of different kinds.

Neural networks consist of layers that analyze an image at different scales. The first layer might recognize broad features like edges, the next layer sees how these edges form simple shapes like circles, the next layer recognizes patterns of shapes, such as two circles close together, and yet another layer might label these pairs of circles as eyes.

This kind of network would be able to recognize eyes in paintings in a wide variety of styles, from Leonardo da Vinci to Van Gogh to Picasso. In each case, the eyes form a similar pattern that the machine can pick out.

Gatys and co went further by training such a network to recognize artistic style; for example, to distinguish a Van Gogh from a Picasso.

Their key discovery was that the ability to distinguish style was entirely separate from the ability to see faces or other objects. In fact, Gatys and co were able to separate this ability and use it in reverse. They fed a picture into the neural network, which then superimposed the style onto the image.

This process allowed them to convert any image into the style of another artist.

This work has been hugely influential. Various groups have used it to produce artworks, comics, or even movies in the style of any chosen artist.

This process works just as well with Picasso, making it possible to produce an image in the style of Picasso’s cubist paintings, or his Rose Period, or indeed his Blue Period.

This is where Bourached and Cann come in. They have taken a manually edited version of the x-ray images of the ghostly woman beneath The Old Guitarist and passed it through a neural style transfer network. This network was trained to convert images into the style of another artwork from Picasso’s Blue Period.

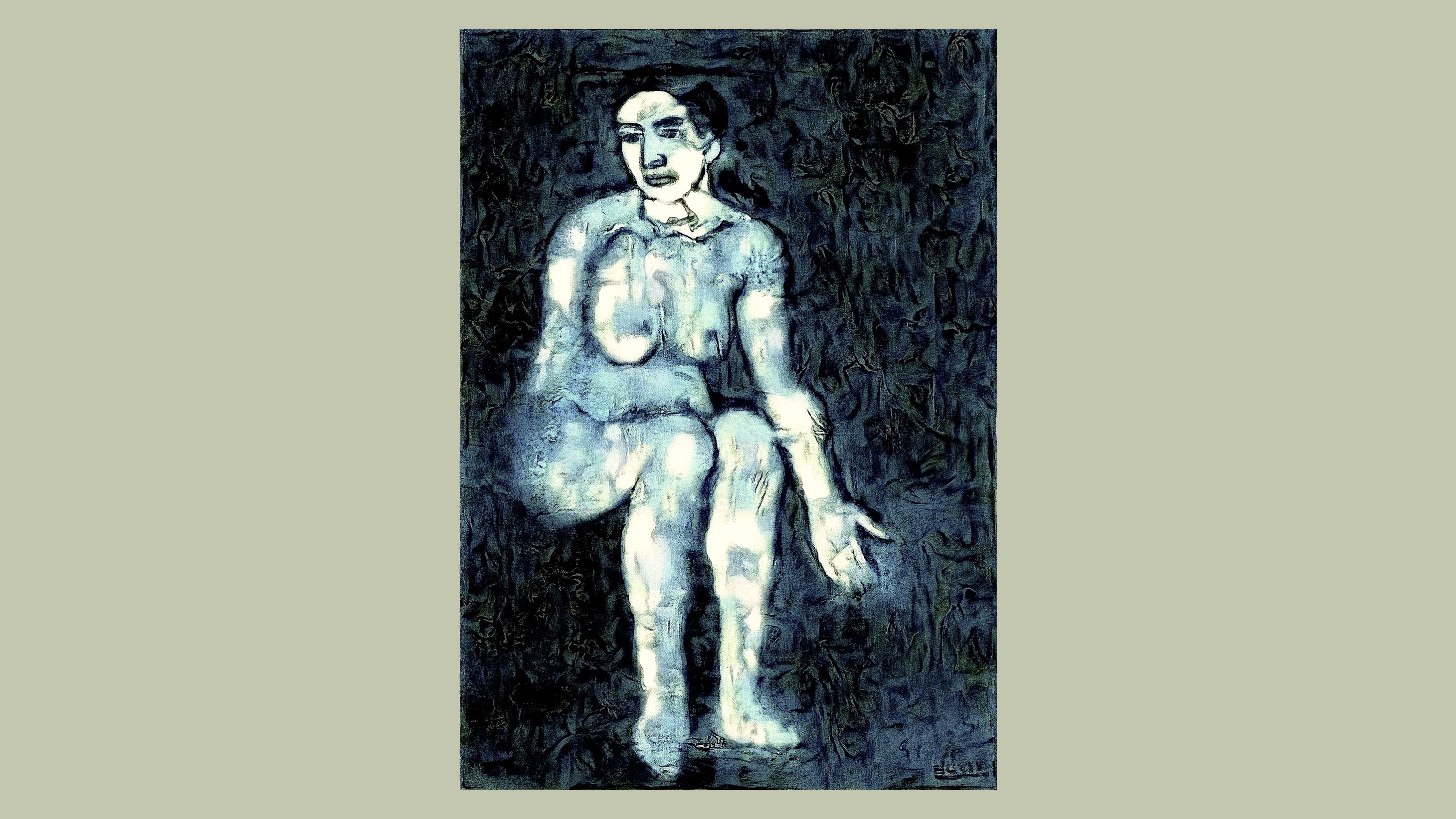

The result is a full-color version of the painting in exactly the style Picasso was exploring when he painted it. “We present a novel method of reconstructing lost artwork, by applying neural style transfer to x-radiographs of artwork with secondary interior artwork beneath a primary exterior, so as to reconstruct lost artwork,” they say.

Of course, there is no way of knowing that Picasso painted the image this way. But Bourached and Cann say their goal is to broaden the insight into an artist’s intentions, mistakes, and musings by reconstructing artwork that has been hidden. “Our method of combining original but hidden artwork, subjective human input, and neural style transfer helps to broaden an insight into an artist’s creative process,” they say.

That’s interesting work that provides a new way to reproduce and study lost artworks. And it is not the only lost picture they have retrieved. The team also reproduced an image thought to have been created by the Spanish painter Santiago Rusiñol and which was then subsequently painted over by Picasso in 1904.

That is surely just the start, and a technique that art historians might feel has the potential to go much further.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1909.05677 : Raiders of the Lost Art

Keep Reading

Most Popular

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Sam Altman says helpful agents are poised to become AI’s killer function

Open AI’s CEO says we won’t need new hardware or lots more training data to get there.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.