Machine learning, meet quantum computing

Back in 1958, in the earliest days of the computing revolution, the US Office of Naval Research organized a press conference to unveil a device invented by a psychologist named Frank Rosenblatt at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory. Rosenblatt called his device a perceptron, and the New York Times reported that it was “the embryo of an electronic computer that [the Navy] expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself, and be conscious of its existence.”

Those claims turned out to be somewhat overblown. But the device kick-started a field of research that still has huge potential today.

A perceptron is a single-layer neural network. The deep-learning networks that have generated so much interest in recent years are direct descendants. Although Rosenblatt’s device never achieved its overhyped potential, there is great hope that one of its descendants might.

Today, there is another information processing revolution in its infancy: quantum computing. And that raises an interesting question: is it possible to implement a perceptron on a quantum computer, and if so, how powerful can it be?

Today we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Francesco Tacchino and colleagues at the University of Pavia in Italy. These guys have built the world’s first perceptron implemented on a quantum computer and then put it through its paces on some simple image processing tasks.

In its simplest form, a perceptron takes a vector input—a set of numbers—and multiplies it by a weighting vector to produce a single-number output. If this number is above a certain threshold the output is 1, and if it is below the threshold the output is 0.

That has some useful applications. Imagine a pixel array that produces a set of light intensity levels—one for each pixel—when imaging a particular pattern. When this set of numbers is fed into a perceptron, it produces a 1 or 0 output. The goal is to adjust the weighting vector and threshold so that the output is 1 when it sees, say a cat, and 0 in all other cases.

Tacchino and co have repeated Rosenblatt’s early work on a quantum computer. The technology that makes this possible is IBM’s Q-5 “Tenerife” superconducting quantum processor. This is a quantum computer capable of processing five qubits and programmable over the web by anyone who can write a quantum algorithm.

Tacchino and co have created an algorithm that takes a classical vector (like an image) as an input, combines it with a quantum weighting vector, and then produces a 0 or 1 output.

The big advantage of quantum computing is that it allows an exponential increase in the number of dimensions it can process. While a classical perceptron can process an input of N dimensions, a quantum perceptron can process 2N dimensions.

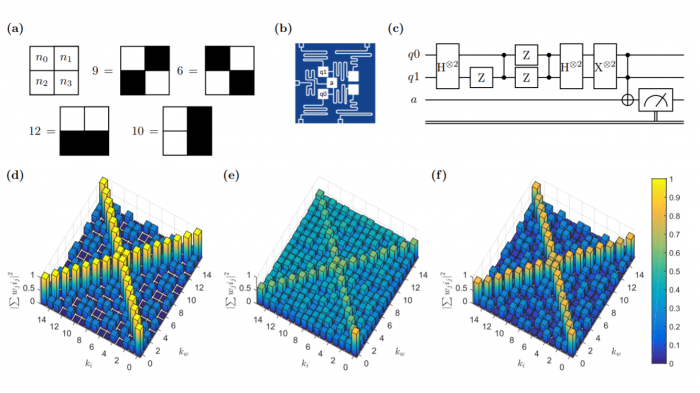

Tacchino and co demonstrate this on IBM’s Q-5 processor. Because of the small number of qubits, the processor can handle N = 2. This is equivalent to a 2x2 black-and-white image. The researchers then ask: does this image contain horizontal or vertical lines, or a checkerboard pattern?

It turns out that the quantum perceptron can easily classify the patterns in these simple images. “We show that this quantum model of a perceptron can be used as an elementary nonlinear classifier of simple patterns,” say Tacchino and co.

They go on to show how it could be used in more complex patterns, albeit in a way that is limited by the number of qubits the quantum processor can handle.

That’s interesting work with significant potential. Rosenblatt and others soon discovered that a single perceptron can only classify very simple images, like straight lines. However, other scientists found that combining perceptrons into layers has much more potential. Various other advances and tweaks have led to machines that can recognize objects and faces as accurately as humans can, and even thrash the best human players of chess and Go.

Tacchino and co’s quantum perceptron is at a similarly early stage of evolution. Future goals will be to encode the equivalent of gray-scale images and to combine quantum perceptrons into many-layered networks.

This group’s work has that potential. “Our procedure is fully general and could be implemented and run on any platform capable of performing universal quantum computation,” they say.

Of course, the limiting factor is the availability of more powerful quantum processors capable of handling larger numbers of qubits. But most quantum researchers agree that this kind of capability is close.

Indeed, since Tacchino and co did their work, IBM has already made a 16-qubit quantum processor available via the web. It’s only a matter of time before quantum perceptrons become much more powerful.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1811.02266 : An Artificial Neuron Implemented on an Actual Quantum Processor

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.