Explainer: What is a blockchain?

What’s that?

A mathematical structure for storing data in a way that is nearly impossible to fake. It can be used for all kinds of valuable data.

Who created the first blockchain?

“I’ve been working on a new electronic cash system that’s fully peer-to-peer, with no trusted third party.” These are the words of Satoshi Nakamoto, the mysterious creator of Bitcoin, in a message sent to a cryptography-focused mailing list in October 2008. Included was a link to a nine-page white paper describing a technology that some are now convinced will disrupt the financial system.

Enforcement

Early civilizations used threat of force as retribution for dealing in bad faith when engaging in trade.

Institutions

The emergence of governments and banks provided organized, central authorities to which we could outsource trust—as long as we trusted them.

The Network

Blockchains distributed across thousands of computers can mechanize trust, opening the door to new ways of organizing “decentralized” enterprises and institutions.

Nakamoto mined the first bitcoins in January 2009, and with that, the cryptocurrency era was born. But while its origin is shadowy, the technology that made it possible, which we now call blockchain, did not arise out the blue. Nakamoto combined established cryptography tools with methods derived from decades of computer science research to enable a public network of participants who don’t necessarily trust each other to agree, over and over, that a shared accounting ledger reflects the truth. This makes it virtually impossible for someone to spend the same bitcoin twice, solving a problem that had hindered previous attempts to create digital cash. And, crucially, it eliminates the need for a central authority to mediate electronic exchange of the currency.

Bitcoin’s popularity began to grow quickly in 2011, after a Gawker article exposed Silk Road, a Bitcoin-powered online drug marketplace. Imitators called “altcoins” began to emerge, often using Bitcoin’s open-source code. Within two years, the total value of bitcoins in circulation had passed $1 billion.

Soon, technologists realized that blockchains could be used to track other things besides money. In 2013, 19-year-old Vitalik Buterin proposed Ethereum, which would record not only currency transactions but also the status of computer programs called smart contracts. Launched in 2015, Ethereum—and now a host of competitors and imitators—promises to make possible a new generation of applications that look and feel like today’s web apps but are powered by decentralized cryptocurrency networks instead of a company’s servers.

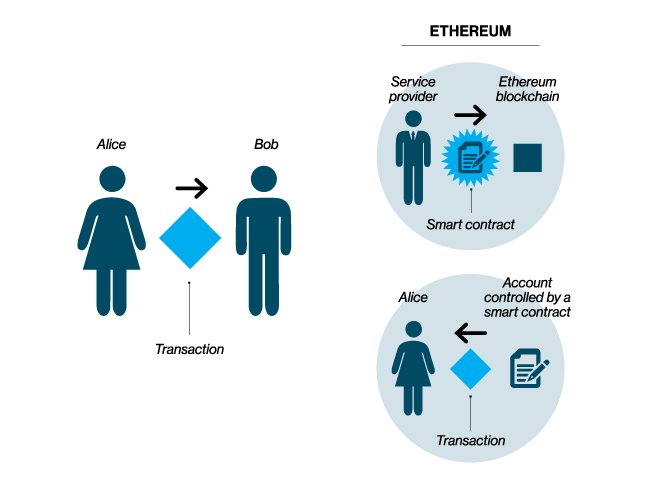

1. A transaction is born

In Bitcoin, a transaction is the transfer of cryptocurrency from one person (Alice) to another (Bob). In Ethereum, which includes a built-in programming language that can be used to automate transactions, there are multiple kinds. Alice can send cryptocurrency to Bob. Or someone can create a transaction that places a line of code, called a smart contract, on the blockchain. Alice and Bob can then send money to an account this program controls, to trigger it to run if certain conditions encoded in the contract are met. A smart contract can also send transactions to the blockchain in which it is embedded.

2. The transaction is broadcast to a peer-to-peer network

Let’s say Alice wants to send some money to Bob. To do so, Alice creates a transaction on her computer that must reference a past transaction on the blockchain in which she received sufficient funds, as well as her private key to the funds and Bob’s address. That transaction is then sent out to other computers, or “nodes,” in the network. The nodes will validate the transaction as long as it has followed the appropriate rules. Then mining nodes (more on those in step 3) will accept it, and it will become part of a new block.

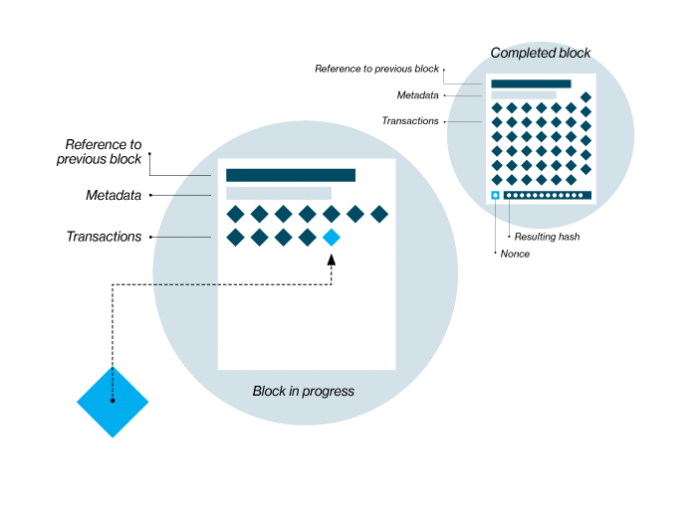

3. The race to create new blocks

A subset of nodes, called miners, organize valid transactions into lists called blocks. A block in progress contains a list of recent valid transactions and a cryptographic reference to the previous block. In blockchain systems like Bitcoin and Ethereum, miners race to complete new blocks, a process that requires solving a labor-intensive mathematical puzzle, which is unique to each new block. The first miner to solve the puzzle will earn some cryptocurrency as a reward. The math puzzle involves randomly guessing at a number called a nonce. The nonce is combined with the other data in the block to create an encrypted digital fingerprint, called a hash.

4. Completing a new block

The hash must meet certain conditions; if it doesn’t, the miner tries another random nonce and calculates the hash again. It takes an enormous number of tries to find a valid hash. This process deters hackers by making it hard to modify the ledger. While some blockchain entities use other systems to secure their chains, this approach, called proof of work, is the most thoroughly battle-tested.

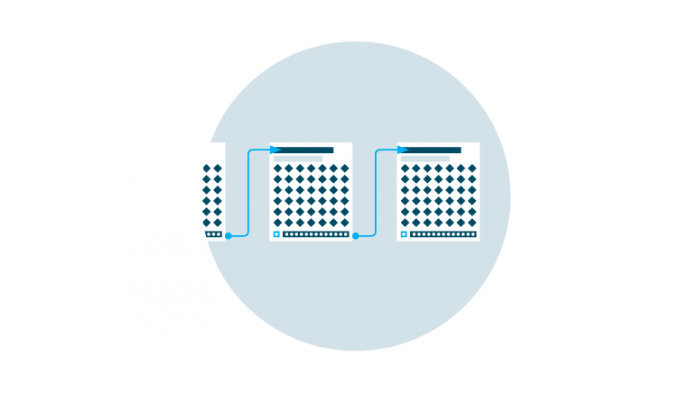

5. Adding a new block to the chain

This is the final step in securing the ledger. When a mining node becomes the first to solve a new block’s crypto-puzzle, it sends the block to the rest of the network for approval, earning digital tokens in reward. Mining difficulty is encoded in the blockchain’s protocol; Bitcoin and Ethereum are designed to make it increasingly hard to solve a block over time. Since each block also contains a reference to the previous one, the blocks are mathematically chained together. Tampering with an earlier block would require repeating the proof of work for all the subsequent blocks in the chain.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.