A New Map of the “Darknet” Suggests Your Local Drug Pusher Now Works Online

In October 2013, the FBI shut down the Silk Road, a website on the so-called darknet that had become notorious for selling illegal drugs and other illegal items and services. Indeed, it had become known as an “eBay for drugs.”

The FBI also arrested its founder, Ross Ulbricht, who was eventually sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. The FBI seized assets including more than 144,000 Bitcoins worth about $29 million at that time, which it later sold at auction.

The incident raised the profile of the darknet—the part of the Web accessed through the Tor communication software, which guarantees anonymity for its users. Since then, numerous other sites have filled the space left by the Silk Road and begun selling a wide range of illegal drugs to anonymous buyers.

This darknet trade offers an entirely new way for drug dealers to sell their wares and for customers to score. The market is worth some $150 million a year—a small fraction of the $300 billion estimated worth of the global trade in illegal drugs—but it is growing rapidly. And that raises some interesting questions.

The drug trade has traditionally operated along well-established supply chains. These chains link the supply with the demand across the entire planet. But the darknet has the potential to fundamentally change these routes, so there is great interest among researchers, law enforcement agencies, and policy makers about how the changes are happening. In particular, they are interested in whether the darknet is having a greater impact on the supply side or the demand side of this chain.

Today we get an answer thanks to the work of Martin Dittus and his pals at the University of Oxford in the U.K. They have mapped the darknet drug trade for the first time and compared it with known patterns of illegal trade. Their analysis provides a unique insight into the way the darknet is changing the illegal drug trade.

The team began by identifying the major marketplaces on the darknet and crawling their content. The biggest marketplaces are AlphaBay, Hansa, TradeRoute, and Valhalla, which together account for about 95 percent of inventory on the darknet.

The team crawled the content of each of these sites to work out the full catalog of products on offer. They used various techniques to find hidden products, such as entering sequential identifiers to see if they corresponded with real pages. That gave them a single snapshot of the market for June/July 2017.

The team then estimated trading volumes by counting the number of buyer reviews—a total of 1.5 million of them. Not everyone leaves a review, so this number is a lower bound on actual trades.

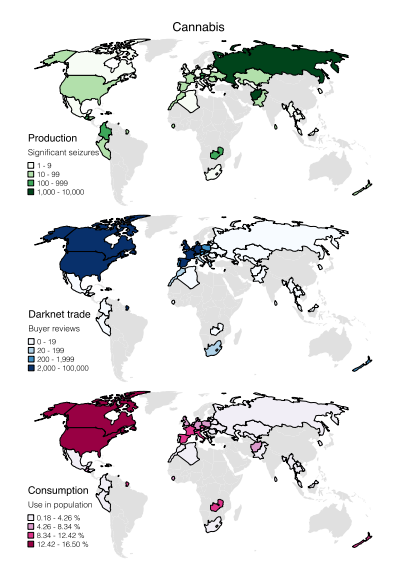

The reviews gave a rough location for each seller and buyer. By this measure, just five countries account for 70 percent of darknet trade: the U.S. (27 percent), the U.K. (22 percent), Germany (8 percent), Australia (8 percent), and Holland (7 percent).

The reviews also revealed the product involved, with the team interested only in cannabis, cocaine, and opiate products. The result is a look at where different types of drugs end up on the darknet.

Finally, the team compared this pattern with the conventional illegal drug market. Dittus and the team gathered government data on drug use in each country. And to see where it was coming from, they looked at government and law enforcement data on drug seizures. That gave them a good overview of the geographical marketplace for the illegal drug trade.

This comparison shows how darknet trades fit into the global supply chain. Dittus and company say the data suggests that darknet traders sit at the “last mile” end of the supply chain, at least as far as cannabis and cocaine are concerned. “We present strong evidence that cannabis and cocaine vendors are primarily located in a small number of consumer countries, rather than producer countries,” they say.

The evidence for opiate trading is less clear. Opiate consumption is highest in the Middle East, Russia, and Asia. However, opiate darknet trading volumes are highest in the “top five” countries, suggesting that there is a different pattern at work here.

According to the team, none of these drugs is shipped over the darknet from countries traditionally associated with producing them. This finding also suggests that the darknet is largely catering to consumers in their home countries.

An important question is whether darknet markets are slowly reorganizing the global drug trade. Dittus and his team say they find little evidence of this in producer countries. Instead, darknet markets primarily play the role of local retailers serving the “last mile” in a small number of rich countries.

That’s an interesting result that sheds some much-needed light onto the murky world of drug dealing over the darknet. It should help law enforcement agencies and policy makers allocate resources accordingly.

More work will be needed to chart the evolution of this new market, however. It’s not hard to see how this kind of activity could undermine conventional law enforcement approaches. But it can also uncover additional information on the nature of this kind of use and its broader impact in society.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1712.10068: Platform Criminalism: The "Last-Mile" Geography of the Darknet Market Supply Chain

Deep Dive

Policy

Is there anything more fascinating than a hidden world?

Some hidden worlds--whether in space, deep in the ocean, or in the form of waves or microbes--remain stubbornly unseen. Here's how technology is being used to reveal them.

A brief, weird history of brainwashing

L. Ron Hubbard, Operation Midnight Climax, and stochastic terrorism—the race for mind control changed America forever.

What Luddites can teach us about resisting an automated future

Opposing technology isn’t antithetical to progress.

Africa’s push to regulate AI starts now

AI is expanding across the continent and new policies are taking shape. But poor digital infrastructure and regulatory bottlenecks could slow adoption.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.