Bitcoin Transactions Aren’t as Anonymous as Everyone Hoped

An increasing number of online merchants now offer the ability to pay using the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. One of the great promises of this technology is anonymity: the transactions are recorded and made public, but they are linked only with an electronic address. So whatever you buy with your bitcoins, the purchase cannot be traced specifically to you.

This is handy for some, but the anonymity is by no means perfect. Security experts call it pseudonymous privacy, like writing books under a nom de plume. You can preserve your privacy as long as the pseudonym is not linked to you. But as soon as somebody makes the link to one of your anonymous books, the ruse is revealed. Your entire writing history under your pseudonym becomes public. Similarly, as soon as your personal details are linked to your Bitcoin address, your purchase history is revealed too.

That raises an important question for people hoping to use Bitcoin to make anonymous purchases: how easy is it to link them with their Bitcoin transactions?

Today we get an answer thanks to the work of Steven Goldfeder at Princeton University and a number of pals. These guys say the way information leaks during ordinary purchases makes it straightforward to link individuals with the Bitcoin transactions they make, even when purchasers use additional privacy protections, such as CoinJoin.

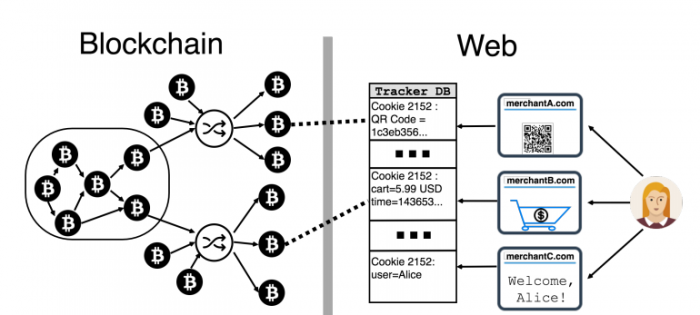

The main culprits are Web trackers and cookies—small pieces of code deliberately embedded into websites that send information to third parties about the way people use the site. Common Web trackers send information to Google, Facebook, and others to track page usage, purchase amounts, browsing habits, and so on. Some trackers even send personally identifiable information such as your name, address, and e-mail.

In this way, information about a transaction leaks onto the Web, where governments, law enforcement agencies, and malicious users can readily collect and analyze it.

The question that Goldfeder and co investigate is how easy it is to use this information to connect people to their Bitcoin transactions. This process requires the eavesdropper to know an individual’s personally identifiable information—name and e-mail, for example—and then to link that with a specific Bitcoin address.

The team began by listing major merchants that allow Bitcoin transactions. They came up with 130 of them, including Microsoft, NewEgg, and Overstock.

They then studied how Web trackers leak information from each of these sites during the purchase process. “We find that at least 53/130 of merchants leak payment information to a total of at least 40 third parties, most frequently from shopping cart pages,” say Goldfeder and co.

Most of this information leakage is intentional for the purposes of advertising and analytics. But the researchers also say some extra information is also sent. “We find that many merchant websites have far more serious (and likely unintentional) information leaks that directly reveal the exact transaction on the blockchain to dozens of trackers,” they say.

That’s bad news for people hoping to keep their Bitcoin purchases anonymous. But even when the exact transaction is kept hidden, it is still possible to make the link when the leak includes the amount and time of the purchase.

In that case, the eavesdropper needs to convert the purchase amount into Bitcoins using the exchange rate at the time and then search the blockchain for a transaction of that amount at that moment. This reveals the Bitcoin address of the user. Any other purchases made using that address are then trivial to track down.

There are a couple of additional factors that make this process trickier. The Web tracker might leak the cost of the product but not include shipping, so the total Bitcoin purchase may not be clear.

There may also be a gap between the time the user viewed the page the information leaked from—the checkout cart, for example—and the time when the purchase was actually made. Bitcoin purchases are time-stamped, so it becomes harder to track them down if the time is not known accurately.

The purchase amount is usually given in a local currency such as dollars or pounds and then converted into Bitcoin at the instant of purchase. Because of the large variability in Bitcoin exchange rates, it can be hard to work out the exact Bitcoin value if the purchase time is not known accurately.

All these factors make it harder to link individuals to their Bitcoin transactions, but it is by no means impossible. “We find that unique linkage is possible in over 60% of cases for realistic values of these parameters,” the researchers say.

There are ways to further hide Bitcoin transactions. One of the most popular is CoinJoin, a service that links users who want to make similar payments and then allows them to pay together. This mixes their bitcoins, making it harder to identify them.

But Goldfeder and co point out that if an individual uses CoinJoin to make several purchases in this way, it is straightforward to link them back: “If the victim employs 3 rounds of CoinJoin and the adversary observes two of the victim’s payments, he can link them back to her wallet (despite mixing) with 98% accuracy.”

There are several ways buyers can protect themselves using tools such as Ghostery, AdBlock Plus, or uBlock Origin. These are useful but can sometimes miss trackers and at other times prevent purchases entirely. “Such defences can be quite effective, but they are far from perfect,” say Goldfeder and co.

All this will come as depressing news to people hoping to preserve their privacy online.

But it will also be music to the ears of law enforcement agencies hoping to track nefarious activities. “Like virtually all deanonymization attacks on cryptocurrencies, our techniques could be used to build forensic tools for law enforcement use,” admit Goldfeder and co.

And like all deanonymization techniques, that will have advantages and disadvantages.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1708.04748 : When the Cookie Meets the Blockchain: Privacy Risks of Web Payments via Cryptocurrencies

Keep Reading

Most Popular

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Sam Altman says helpful agents are poised to become AI’s killer function

Open AI’s CEO says we won’t need new hardware or lots more training data to get there.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.