Scientists Used CRISPR to Put a GIF Inside a Living Organism’s DNA

The promise of using DNA as storage means you could conceivably save every photo you’ve ever taken, your entire iTunes library, and all 839 episodes of Doctor Who in a tiny molecule invisible to the naked eye—with plenty of room to spare.

But what if you could keep all that digital information on you at all times, even embedded in your skin? Harvard University geneticist George Church and his team think it might be possible one day.

They’ve used the gene-editing system CRISPR to insert a short animated image, or GIF, into the genomes of living Escherichia coli bacteria. The researchers converted the individual pixels of each image into nucleotides, the building blocks of DNA.

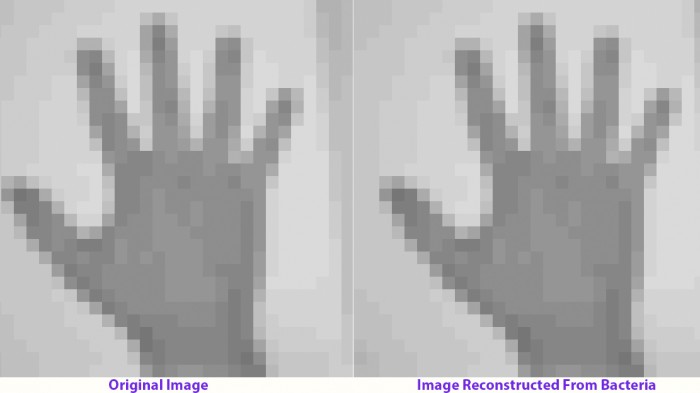

They delivered the GIF into the living bacteria in the form of five frames: images of a galloping horse and rider, taken by English photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who produced the first stop-motion photographs in the 1870s. The researchers were then able to retrieve the data by sequencing the bacterial DNA. They reconstructed the movie with 90 percent accuracy by reading the pixel nucleotide code.

The method, detailed today in Nature, is specific to bacteria, but Yaniv Erlich, a computer scientist and biologist at Columbia University who was not involved in the study, says it represents a scalable way to host information in living cells that could eventually be used in human cells.

The modern world is increasingly generating massive amounts of digital data, and scientists see DNA as a compact and enduring way of storing that information. After all, DNA from thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years ago can still be extracted and sequenced in a lab.

So far, much of the research into using DNA for storage has involved synthetic DNA made by scientists. And this GIF—only 36 by 26 pixels in size—represents a relatively small amount of information compared to what scientists have so far been able to encode in synthetic DNA. It’s more challenging to upload information into living cells than synthesized DNA, though, because live cells are constantly moving, changing, dividing, and dying off.

Erlich says one benefit of hosting data in living cells like bacteria is better protection. For example, some bacteria still thrive after nuclear explosions, radiation exposure, or extremely high temperatures.

Beyond just storing data, Seth Shipman, a scientist working in Church’s lab at Harvard who led the study, says he wants to use the technique to make “living sensors” that can record what is happening inside a cell or in its environment.

“What we really want to make are cells that encode biological or environmental information about what’s going on within them and around them,” Shipman says.

Though this technique won’t be used anytime soon to load large quantities of data into your body, it could prove to be a valuable research tool. One possible use would be to record the molecular events that drive the evolution of cell types, such as the formation of neurons during brain development.

Shipman says you could deposit these bacterial hard drives in the body or anywhere in the world, record something you might be interested in, collect the bacteria, and sequence the DNA to see what information has been picked up along the way.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.