Data Scientists Chart the Tragic Rise of Selfie Deaths

Selfies became all the rage in the early part of the century, when smartphones with forward-facing cameras first hit the market. And their popularity has been explosive; last year, some 24 billion selfies were uploaded to Google Photos.

But this trend has been accompanied by a more tragic one. In 2014, 15 people died while taking a selfie; in 2015 this rose to 39, and in 2016 there were 73 deaths in the first eight months of the year. That’s more selfie deaths than deaths due to shark attacks.

That raises an interesting question—how are these people dying, and is there a way to prevent these kinds of accidents?

Today, we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Hemank Lamba at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and a few friends. They’ve studied the nature of selfie deaths and have begun the tricky task of finding a way to warn people when the process of taking a selfie could be dangerous.

Their work begins by assembling a data set of selfie deaths by scouring newspapers reports from around the world. They define a selfie death as “a death of an individual or a group of people that could have been avoided had the individual(s) not been taking a selfie.”

To ensure that the reports are reputable, they look only at newspaper websites that are in the top 5,000 global sites ranked by Alexa or within the top 1,000 in a specific country. “The earliest article reporting a selfie death that we were able to collect was published in March 2014,” say Lamba and co.

In this way, the team found 127 selfie deaths. They then went through each report to determine the location, the reason for the death, and the number of people who died.

That produced a small database of selfie death facts. It turns out that most deaths occurred in India—76 of them, more than half of the total, and a number that dwarfs the death toll in other countries. The next highest were nine deaths in Pakistan, eight in the U.S., and six in Russia.

The team also found that the most common cause of death was falling from a height. This reflects the penchant for people taking selfies at the edge of cliffs, at the top of tall structures, and so on.

Water also accounts for a large number of deaths. And a significant number involve water and heights—things like jumping into the sea from a height and so on.

Interestingly, in India, trains feature significantly as a cause of selfie death. “This trend caters to the belief that posing on or next to train tracks with their best friend is regarded as romantic and a sign of never-ending friendship,” they say.

Another feature is the significant proportion of selfie deaths in the U.S. and Russia caused by weapons. “This might be a consequence of the open gun laws in both the countries,” the team suggests.

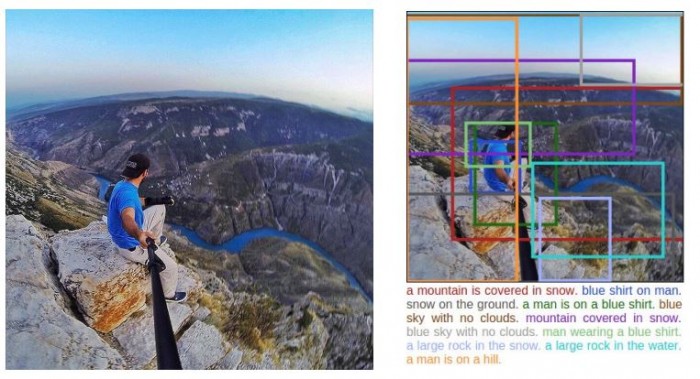

Lamba and co then attempt to identify signs that could indicate that a selfie may be risky. Their goal is to build an app that warns people if selfie deaths have occurred nearby or if their selfie activity might otherwise be risky.

They do this by looking for patterns in the selfie death data set and then use this to train a machine-learning algorithm to spot similar patterns in other selfies downloaded from Twitter. For example, a selfie taken at a local high point might indicate danger, as might one taken close to train tracks.

Their test involves feeding their algorithm with some 3,000 other selfies posted to Twitter and asking it to judge whether the images involved dangerous activity. The team claims an accuracy of over 70 percent.

Clearly, the researchers have some way to go before they can build a selfie death warning system. But it is a worthy goal, particularly in India, where selfie deaths are more common than in other parts of the world. Just why this is so would be worth investigating in itself.

What is it about Indian selfie culture that makes it so much more dangerous than in other parts of the world? Perhaps that’s something for Lamba and co to investigate in future work.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1611.01911: Me, Myself and My Killfie: Characterizing and Preventing Selfie Deaths

Deep Dive

Policy

Is there anything more fascinating than a hidden world?

Some hidden worlds--whether in space, deep in the ocean, or in the form of waves or microbes--remain stubbornly unseen. Here's how technology is being used to reveal them.

A brief, weird history of brainwashing

L. Ron Hubbard, Operation Midnight Climax, and stochastic terrorism—the race for mind control changed America forever.

What Luddites can teach us about resisting an automated future

Opposing technology isn’t antithetical to progress.

Africa’s push to regulate AI starts now

AI is expanding across the continent and new policies are taking shape. But poor digital infrastructure and regulatory bottlenecks could slow adoption.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.