Intel Tries to Rearchitect the Computer—and Itself

The world’s biggest chip maker says it’s time to start building computers differently—and it wants to sell the new hardware technologies needed to do it.

In San Francisco last week Intel executives showed off two new technologies for storing data and moving it around that could shake up established ways of designing computers. The new technologies are primarily being targeted at the giant data centers that power mobile apps, websites, and emerging ideas in artificial intelligence. They could also benefit consumers more directly by appearing in consumer products.

Intel needs some new markets. In April the company announced it was laying off 12,000 workers and abandoning making chips for mobile devices, a huge market Intel missed out on. The company has also had to slow the pace at which it brings out new generations of smaller transistors, a trend that has underpinned the industry and Intel’s business for decades (see “Intel Puts the Brakes on Moore’s Law”).

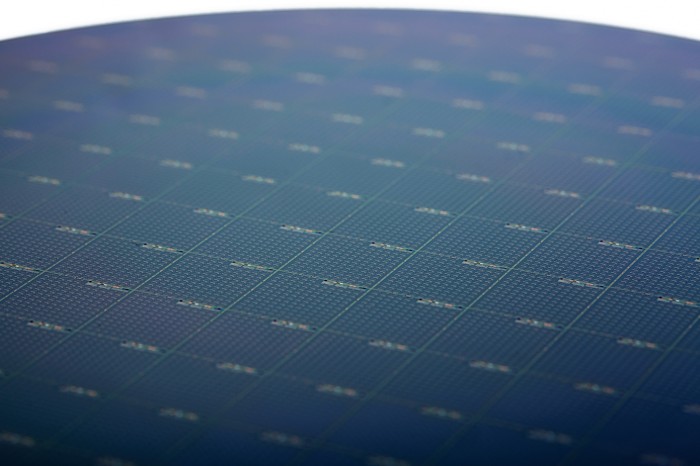

One of Intel’s new technologies is a form of data storage that’s faster than the flash disk used in laptops and data centers today. Intel calls it Optane, and it is based on technology called 3D Xpoint, developed in collaboration with memory manufacturer Micron. Intel has not disclosed how 3D Xpoint works, but it is believed to write data by heating a glass-like “phase change” material (see “A Preview of Future Disk Drives”).

Intel says it will launch Optane disks in 2016 and memory chips that fit into the same slots as a computer’s RAM in 2017. At Intel’s annual developer conference last week, Frank Hady, a technical leader on the project, showed a computer with a prototype Optane disk processing database records in a task common in the data centers of companies such as Facebook at three times the speed of a computer with a flash disk. Hady said an Optane drive can locate and access a piece of data in a tenth the time a flash disk, or SSD, would need.

In the past few years, flash disks have been enthusiastically adopted by computing companies to make servers and consumer PCs snappier. If Optane drives appear in PCs, they should also boost performance. And Ethan Miller, a professor and director of the Center for Research in Storage Systems at the University of California, Santa Cruz, says that Intel and Micron’s technology could have an even larger impact than flash on how people build and use computer systems if researchers and companies outside Intel embrace and experiment with it.

For instance, Optane memory chips might offer ways to make the expensive data center systems that underpin search engines and social networks much more efficient—something large Internet companies such as Facebook would gladly pay for.

Optane memory chips also retain their data when powered off, unlike RAM. That should make data center systems quicker to recover after crashes or power outages.

Intel also announced a new way to move data between computers last week. The company has begun manufacturing silicon chips with tiny, built-in lasers as a way to replace some copper cables inside data centers with fiber optic ones. Fiber optic links are today mostly limited to long-range connections, such as telecom networks, because of the size and expense of the components needed. Intel’s technology can send 100 gigabits of data per second over a single optical fiber a few millimeters thick.

Production problems derailed Intel’s previous promise to launch its silicon photonics technology in 2013 (see “Intel’s Laser Chips Could Make Data Centers Run Better”). But the company now appears to be on track to beat IBM, Cisco, and others working on similar technology. “We are the first to light up silicon,” said Diane Bryant, who leads Intel’s data center business, at the company’s event last week.

Bryant said that Intel’s silicon photonics technology will initially be used to connect network gear inside data centers. But after that it will be used to link up servers, and Intel also hopes to replace some of the metal cables inside individual computers with silicon photonics links. That could free engineers to rethink conventional computer designs, which are constrained by the performance of copper cables. Intel has previously said silicon photonics could eventually be used to make data cables and computers used by consumer faster.

Microsoft’s Kushagra Vaid, who leads work on the hardware behind its Azure cloud computing service, spoke alongside Bryant. He said he expected to rely on the technology as a way to keep increasing the volume of data his fleets of servers can process, because they are going to become constrained by conventional connections. “We need some new technologies,” he said. “It’s a great way to continue that scaling.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Sam Altman says helpful agents are poised to become AI’s killer function

Open AI’s CEO says we won’t need new hardware or lots more training data to get there.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.