Find Out Which Appliance Is Sucking All Your Power

Is your garage door opening right now? Is your washing machine running? A growing number of products attempt to give consumers data on the sources of their household energy use—crucial data for home efficiency efforts and utility peak-hour conservation programs.

But Sense, a startup in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the first to offer a consumer product that reads incoming household power levels a million times per second—enough to tease out telltale clues to which specific appliances, even low-wattage ones, are operating in real time. “It’s at the cutting edge of what I have seen people attempting in this area,” says Michael Baker, a vice president at SBW, an energy efficiency consultancy in Seattle.

The company says it can accurately disaggregate 80 percent of home energy use; it can do things like detect a microwave oven through its very specific startup and operating power “signature,” or sense a washing machine thanks in part to subtly increasing demand on the motor as the drum fills with water. As it identifies garage door openers, toasters, microwave ovens, washing machines, heaters, and refrigerators, it displays them on an app as a newsfeed and a series of labeled bubbles.

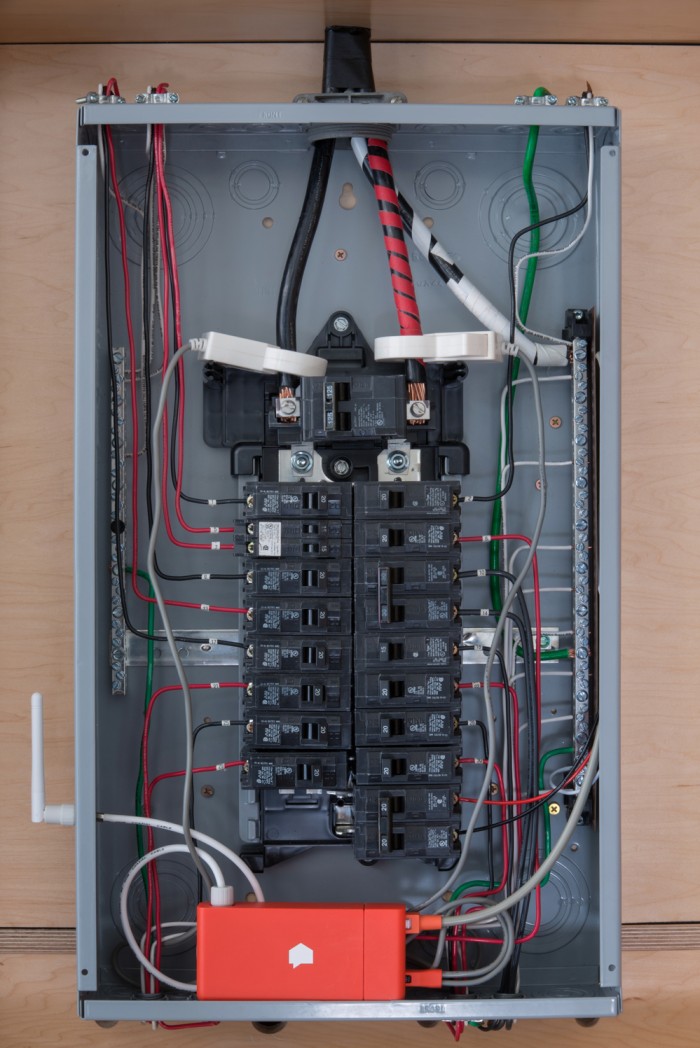

Sense—founded by speech-recognition veterans whose technology ended up in Samsung’s S-Voice and Apple’s Siri—consists of a box about the size of an eyeglasses case installed inside or next to an electrical service panel. Two inductive current sensors sense current, and two cables power the box and sense voltage. The box does some onboard processing, and then uses Wi-Fi to send data to the cloud for further analysis and aggregation with data from other users to improve its accuracy.

While Sense's initial business model is based on selling the hardware for $299, the long-term play is in the data: Sense will retain rights to the data and expects to eventually serve personalized recommendations. It also hopes to sell anonymized data and insights to companies like utilities or insurance companies.

Green Mountain Power, an electric utility serving 260,000 customers in Vermont, is planning to pilot the technology in customer homes in the town of Panton. The goal: to get homeowners interested in monitoring home energy usage—the necessary first step toward getting them to do things like shut off equipment at critical peak times or better align their household usage with household solar power generation (another data point Sense can track).

The utility already has so-called “smart meters” that collect data at eight- to 12-second intervals and plot it for customers in an app, but “we found that data at this resolution isn’t all that interesting,” says Todd LaMothe, a software development manager at the utility. “We were pleasantly surprised by the quality of the appliance disaggregation and data visualization in the Sense app. Your home is interacting with you—it’s telling you what it’s doing. That’s the next generation we are looking for.” (Sense requires no smart meters or other advanced technology in the home, other than a Wi-Fi connection.)

A number of consumer systems for monitoring home energy exist—but are generally of low resolution and look only at entire-household energy use. Navetas allows you to track electricity consumption in real time, analyze trends, and set goals, but does not disaggregate what is causing the load. Bidgely services utilities that have installed smart meters. By sampling meter data every few seconds, it can spot trends or major anomalous events, like a big overnight load that suggests an appliance such as an electric oven was accidentally left on. Another startup, Neurio, is developing a similar system but is only able to see high-wattage devices.

As more consumer appliances become Internet-controlled, Sense can govern interactions with them. “Intelligence in the home starts with good data about what is going on, so that’s our focus right now—developing that data,” says Sense CEO and cofounder Michael Phillips, who a decade ago cofounded Vlingo, a voice-recognition startup that developed speech recognition for mobile phones and virtual assistants. “Until now nobody has been able to make this work, because the real world is more challenging than expected.”

It can take a month of “observing” the home before the technology will fully identify what’s doing what. I tested it at my house over the past week. So far it has detected my fridge, washing machine, and dryer. I was surprised to see a big spike in demand at certain times when my dishwasher was running. That’s how I learned that it takes 1,200 watts just to heat water within dishwashers. I also saw that my house never consumes less than 64 watts, due to “always on” things like routers.

I found myself switching things on and off to see what they consumed. I quickly realized that my decades-old attic fan—out of sight, out of mind—was consuming 500 watts. So I’m already planning to get rid of it and install a gable vent instead, and let convection do the same job.

Deep Dive

Computing

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.