How First Solar Is Avoiding the Industry’s Turmoil

In a warehouse in an anonymous industrial district just off the 101 freeway, in Santa Clara, First Solar is testing the limits of solar-cell technology. Inside the white-walled space, machines deposit cadmium telluride onto sheets of super-pure glass to make solar panels. On the day I visited, this spring, the place had the hushed, intense air of a hospital operating theater.

In the last three years, First Solar has invested heavily in its R&D facilities, including the Santa Clara lab. While today’s solar market is dominated by cells made from silicon, First Solar produces thin-film cells (which, as the name implies, are less thick and more flexible than conventional silicon cells) that are made of a compound of the elements cadmium and tellurium. The Arizona-based company is betting that cells made from cadmium telluride can be much more efficient at converting energy from the sun into electricity.

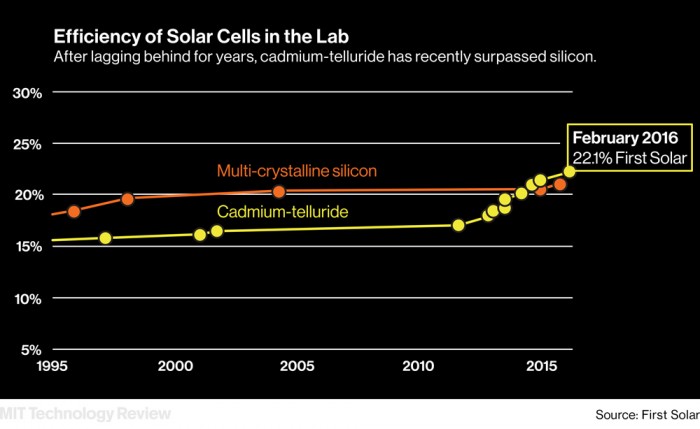

Last month First Solar said it has set a new efficiency record for cadmium telluride cells: devices produced in its research lab converted 22.1 percent of the energy in sunlight into electricity (see “First Solar’s Cells Break Efficiency Record”). In the field, First Solar’s cells have reached nearly 17 percent efficiency, comparable to silicon-based solar panels. While silicon has traditionally been more efficient than cadmium telluride, First Solar’s recent results indicate that its cells are rapidly surpassing silicon.

First Solar’s quest to invent the future of solar power comes amid turmoil that has engulfed many solar companies in the wake of the collapse of SunEdison (see “Why Solar Giant SunEdison Might Be Doomed”). Despite the fact that the last quarter of 2015 was the best three-month period in the industry’s history in terms of megawatts installed, and that Congress in December extended the investment tax credit, which provides credits worth 30 percent of the value of installations, shares in big solar developers such as Sunrun and SolarCity have lost nearly half their value in recent months. First Solar’s stock, by contrast, jumped by 17 percent after it reported strong 2015 results in late February. More important, unlike most of its competitors, First Solar is profitable: the company made $546 million in 2015 on nearly $3.6 billion in revenue.

Founded in 1999, First Solar is both a supplier of solar panels and a developer of its own large solar farms. Over the last decade, as low-cost manufacturers in China have driven the cost of commodity solar panels down, First Solar has invested heavily in sophisticated and expensive cell technology. The company spends about 4 percent of its revenues on research and development, nearly twice the solar industry average.

Even as the industry has focused on silicon-based solar cells, which now control close to 95 percent of the market, First Solar has stuck with cadmium telluride as the basic material for its thin-film technology. And unlike Solar City, which is building a $750 million factory to make silicon solar cells in Buffalo, First Solar concentrates on the market for utility-scale solar farms rather than the residential rooftop market.

As the chart above shows, multicrystalline-silicon solar cells (which represent about 80 percent of the silicon market) have stalled at around 20 percent efficiency for research cells in the lab, which converts to about 16 percent in the field. Earlier this month, First Solar said that its cells could reach 24 percent efficiency within two years and that in real-world operation its panels could hit 19 percent in three years. Cadium telluride is especially effective in hot, humid regions such as the U.S. Southeast and South Asia, where much of the growth in the utility-scale solar market is expected to happen in the coming years.

Thin-film cells are also easier to make. First Solar’s vapor deposition process takes about three and a half hours to make a solar panel, from clean sheet of glass to finished product. Making conventional silicon panels requires first baking the silicon in a high-temperature furnace and can take more than two days from start to finish. Focusing on efficiency improvements and manufacturing innovations, First Solar has succeeded where other makers of cadmium telluride solar panels have failed. In 2013 First Solar acquired GE’s technology after GE canceled plans for a $300 million plant in Colorado.

Guggenheim Securities research analyst Sophie Karp estimates that silicon panels cost from 69 to 80 cents per watt to manufacture; thin-film cadmium telluride ones cost from 60 to 70 cents. That means that, for First Solar, there is a simple calculation: more-efficient panels manufactured at lower cost than its conventional rivals.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.