Ivanpah’s Problems Could Signal the End of Concentrated Solar in the U.S.

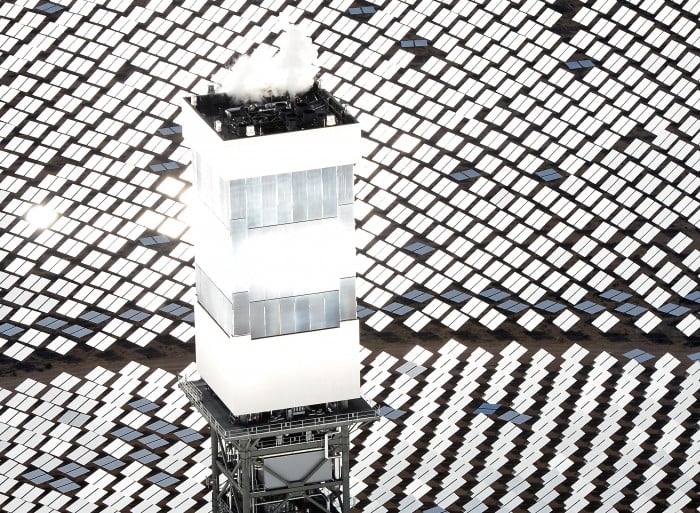

When it first came online in late 2013, the massive Ivanpah concentrated solar power plant in the California desert looked like the possible future of renewable energy. Now its troubles underline the challenges facing concentrated solar power, which uses mirrors to focus the sun’s rays to make steam and produce electricity.

Last week the California Public Utilities Commission gave the beleaguered Ivanpah project, the world’s largest concentrated solar facility, one year to increase its electricity production to fulfill its supply commitments to two of the state’s largest utilities (see “One of the World’s Largest Solar Facilities Is in Trouble”). The $2.2 billion plant is designed to have 377 megawatts of capacity. But it has been plagued by charges of numerous bird deaths (the birds are supposedly zapped by the fierce beams between the mirrors and the collecting tower; these charges have been largely discounted by environmental impact studies) and accusations of production shortfalls.

Saying that over the last 12 months the facility has reached 97.5 percent of its annual contracted production, BrightSource officials dismissed the supply issues as a normal part of the plant’s startup phase. But the troubles at Ivanpah have joined the delay or cancellation of several high-profile projects as evidence that concentrated solar power could be a fading technology.

Last year BrightSource canceled a 500-megawatt concentrated solar project planned for Inyo County, California. That move followed the 2014 decision of French nuclear giant Areva, which acquired an Australian concentrated solar startup called Ausra in 2010, to exit the solar business after losing “tens of millions” of dollars. And the Spanish company Abengoa, which has developed several large concentrated solar projects and received $2.7 billion in loan guarantees from the U.S. Department of Energy, is in talks to restructure its debt and is in danger of becoming Spain’s largest-ever bankruptcy.

Most of these shuttered projects have been doomed by one factor: cost. Given cheap natural gas and the continued fall in solar photovoltaic prices, concentrated solar has been priced out of the market. Concentrated solar plants use thousands of mirrors to focus the sun’s rays on a tower, where they heat a liquid to make steam. The mirrors, known as heliostats, are motorized so as to track the sun’s path over the course of the day. The process has certain advantages over solar photovoltaic technology, including higher efficiencies in terms of the amount of solar energy converted to electricity, but in today’s low-cost environment it’s simply too expensive.

At least that’s true in the United States. Executives at BrightSource and rival SolarReserve point out that a number of projects are moving forward in other countries that lack low-cost supplies of natural gas, particularly in the Middle East and Africa. China, which is plowing billions of yuan into clean energy schemes in order to reduce its dependency on coal, plans to build at least a gigawatt of concentrated solar capacity in the coming years, and could expand that to 10 gigawatts. Going forward, both companies also plan to add energy storage capacity, in the form of molten salt, that can enable new plants to continue producing electricity for as much as 10 hours when the sun's not shining.

For now, says SolarReserve CEO Kevin Smith, market conditions in the U.S. “have forced us overseas.” SolarReserve is developing a 100-megawatt in South Africa, known as Redstone. And BrightSource is building a 121-megawatt facility, featuring the world’s tallest solar tower collector, at Ashalim in Israel. “You need to look beneath the surface and beyond the U.S.,” says Joe Desmond, senior vice president of marketing at BrightSource.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.