Apple Hopes You’ll Talk to Your iPhone and Call Your Doctor in the Morning

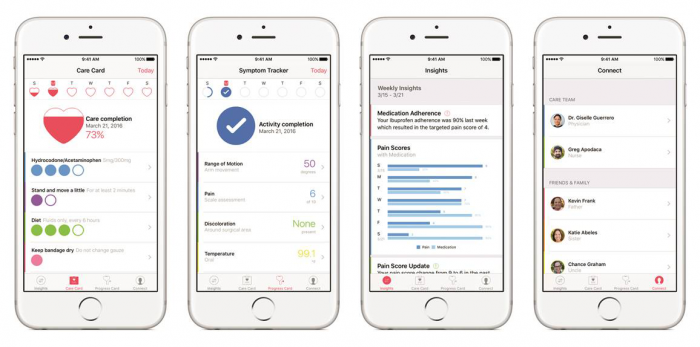

Apple wants to put its devices at the center of health care by figuring out how to solve medicine’s version of the last-mile problem. Today, Apple launched software to help hospitals and others more easily create apps that let patients manage their own conditions, such as by following a digital version of doctors’ orders, recording and tracking symptoms (with medical selfies, among other methods), using dashboards to check their progress against recovery goals, and uploading reports to hospital medical records systems.

The CareKit framework, which will be released to developers in about a month, sprang out of Apple’s experience since last year with medical research projects carried out on the iPhone. One, a study of Parkinson’s disease, suggested that an app that asks volunteers to perform finger taps and other dexterity tests on their phones could help patients adjust their drugs and might actually be able to diagnose the disease.

“We were starting to see the potential results, and we think it’s a profound change,” Jeff Williams, Apple’s chief operating officer, said in an interview in December.

People close to Apple describe the company as “ecstatic” over the findings, and over anecdotal reports that the pulse monitor in the Apple Watch has identified serious health crises, including allergic shock or heart irregularities.

Apple says it thinks patients and doctors are ready to see—and share—more data from their phones. And it’s in a big hurry to help. CareKit appears to have been developed on the fly since January. [Update 3/22: Apple wrote us to say the modules that became CareKit "have been in the works for some time."] As of yesterday, Apple was still deciding what to call various features.

The company today announced about a half-dozen apps that are in development, including an updated version of mPower, the Parkinson’s app; another by the Texas Medical Center to help surgery patients track their recovery; and one, from the startup Glow, to guide women through pregnancy.

Apple may be promoting new ways to track and trade health information, but it’s not yet proposing to diagnose diseases or have the apps play doctor. That’s because doing either of those things would require approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and, consequently, further research to determine if the benefits are real.

In fact, today’s apps look like an incremental step. But Apple seems to have the ambition of disrupting medicine. For instance, Stephen Friend, an Apple advisor who is head of Sage Bionetworks, a Seattle nonprofit that advocates for open science and helped developer mPower, says his aim is to do for medicine what Google’s AlphaGo just did for the board game Go: use data to play the game as well as the experts. Friend says that for now, though, “this is like Pong. This is the beginning.”

Apple’s strategy

Williams, who is Apple’s second-in-command and directly oversees Apple’s manufacturing and software development, says the company’s health strategy came about almost by accident over the last two years. “We didn’t start with a grand plan to say Apple is going after health. It really happened organically,” says Williams. Others say Apple absolutely has a strategy. It wants to make itself critical to consumers' health care and has been taking a series of well-thought-out steps to get there.

One disappointment was that the slick-looking Apple Watch hasn’t turned out to be the killer health device Apple hoped for. Executives in Cupertino didn’t dispute a Wall Street Journal report that several sensors, like a blood oximeter, were pulled at the last minute because they weren’t accurate enough. Apple sold about 15 million watches last year.

Instead, the inspiration for today’s announcements evolved from a different effort. A year ago, working with Friend, Apple created software called ResearchKit to assist medical researchers who wanted to carry out surveys and studies among iPhone owners. The idea was basically to crowdsource medical research. By now, there are at least 20 studies ongoing—on melanoma, asthma, heart disease, and energy drinks—that had enrolled over 100,000 patients.

Unlike other diseases, which are diagnosed from a blood draw or scan, Parkinson’s is still diagnosed in person by a physician, who rates a person’s ability to carry out various coördinated movements. The mPower researchers, who have collected data on more than 9,000 people, believed their phone data was showing them who needed to change their medication. It also appeared to show who had the disease. Some people who had signed up as healthy “controls” appeared to have Parkinson’s. Maybe they’d checked the wrong box. Or maybe they didn’t even know they were sick.

“The app enabled research to be conducted in unprecedented ways,” says Ray Dorsey, a Parkinson’s researcher at the University of Rochester Medical School, who helped create the mPower app. “The question then became, if you can press a button and participate in research, can you press a button and access care? For Parkinson’s we think the answer is yes.”

Dorsey says a phone app able to diagnose or monitor Parkinson’s could benefit millions of people in China and other parts of the world who don’t have access to neurologists. It could also help many Americans with Parkinson’s. Dorsey says 40 percent of Americans with the disease who are over 65 don’t see a neurologist.

Williams says he immediately wanted to know when the app would be turned into a clinical tool. But some neurologists Apple consulted with balked at that idea, saying they’d have to study the data first, possibly for years.

By December, Williams had decided to apply some “impatience” to the problem. The company, he said then, had decided to “push” the Parkinson’s app concept forward “to show how it can actually be used in a clinical therapy setting with people.”

Since then, plans for a single Parkinson’s app appear to have evolved into the broader software concept that Apple presented today. Friend says mPower will add features so that patients can track their response to medications and create a monthly PDF report that could be e-mailed to doctors.

One question facing Apple in its efforts to give patients more data is at what point do phone-tracking apps become regulated “medical devices.” Apple has met with the U.S Food and Drug Administration about its app plans and, according to a summary of one of those meetings, the company believes that with more sensors on mobiles, there is an “opportunity to do more with devices, and that there may be a moral obligation to do more.”

The FDA sees a distinction between apps that simply track information and those that give a diagnosis or other specific medical guidance. A test that measures blood sugar levels would be regulated, but an app that lets a person see the information from glucose readings would not be. Where things could get murky is with apps like mPower that seek to collect meaningful measurements directly off the phone.

Williams says data collected by the phone is no different, in theory, than what a patient could write down about themselves on a piece of paper, and so shouldn’t be regulated. In practice, there could be important differences, since the phone can gather 500,000 data points on an individual over the course of a few months. “That is still within the tracking realm,” Friend argues. “But if it said, I noticed this, and you should do that, that’s the guidance realm, and we aren’t doing that.”

No one listening?

Each of the apps announced today could be quite different. The app being developed by the Texas Medical Center is closer to an interactive, digital version of the thick packet of advice that patients take home after a surgery, but it will also collect information from patients, says William McKeon, chief strategy and operating officer for the hospital conglomerate, which included MD Anderson Cancer Center.

McKeon says the center’s app will communicate directly to his hospital’s electronic medical record. These days that’s necessary for doctors to use it. “If the app is outside of the electronic medical record, physicians will think it’s a Fitbit. They will say, ‘Great, Antonio, you’ve been active,’ but they can’t use it,” he says.

By encouraging developers to connect people’s phones to hospital computers, do tech companies run the risk of overwhelming doctors with information they don’t need? McKeon says doctors at his hospital voted against encouraging patients to take pictures of their chest incisions as they healed, “The physicians said we don’t want patients turning into doctor, saying, ‘Ooh, this looks a little different,’” he says. For the most part, he says, the app would be there to reassure patients when everything is going smoothly.

Patients will also need to know that just because they’re connected to a hospital, no one is going to call them at 2 a.m. if their blood glucose levels spike. “There is no one sitting on the end of a line watching everything,” he says. “We don’t want to interrupt the normal things—if you feel bad, call your doctor, go to the ER. Legally we have to say this is adjunct information and that is your responsibility. The physician cannot be on the hook.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.