Facebook’s New Map of World Population Could Help Get Billions Online

Facebook keeps its map of the social connections of the 1.6 billion people who use the service each month to itself. But it is giving away for free new maps it is building that describe patterns of population density in the world’s poorest countries in unprecedented detail.

Facebook wants those maps to help it figure out how to deploy the solar-powered drones and ground-based infrastructure it says can help get Internet access to a sizeable chunk of the more than four billion people who are not online today. The company says 10 percent of the world’s population lives in places where connectivity is not available. It is working with Columbia University to release its new maps so that other companies and organizations can use them, too.

Robert Chen, director of Columbia’s Center for International Earth Science Information Network, believes the maps will have many uses beyond Internet access projects. “These higher resolution data will be useful in optimizing the location of health and sanitation facilities, planning energy and transportation networks, improving resource management and access, and facilitating humanitarian assistance,” he says.

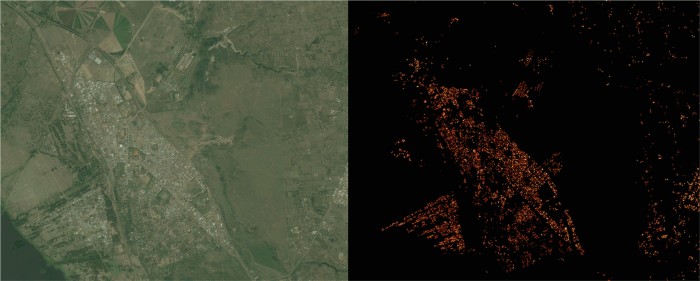

Facebook’s new maps show population density on a grid with squares just five meters across. Chen’s center offers one of the best existing maps of the world’s human population, with a resolution of one kilometer. A project called WorldPop, supported by the World Bank, offers maps of low- and middle-income countries with a resolution of 100 meters.

Facebook’s maps are made using image-recognition software trained to read satellite images for signs of human habitation and how dense it is—houses and infrastructure such as roads and parking lots. The resulting information on the patterns and density of development are combined with available census data for different regions to estimate population density.

The maps released by Facebook on Monday cover 20 countries and 21.6 million square kilometers, including India, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, and several other African nations. Creating the maps took billions of satellite images and thousands of computers working for weeks. The social network is asking for feedback before generating maps for other countries where many people have poor or nonexistent access to Internet infrastructure.

Yael Maguire, engineering director at Facebook’s Connectivity Lab, which is developing the company’s “Aquila” drones and other Internet infrastructure projects, says the data has already helped shape the company’s plans.

The new maps show that people in rural areas tend to clump together in dense pockets more than was suggested by less fine-grained maps, he says. That means it should take fewer drones and shorter links to existing communications infrastructure to cover most people in a given area, says Maguire.

Nicholas Negroponte, an MIT professor who founded the One Laptop Per Child project and is also working on ideas to widen Internet access, says the new maps could also be used to help plan new fiber optic lines, which function as the backbone of Internet infrastructure. But projects aimed at expanding access should also be careful of focusing only on population-dense areas, he says. “Internet access itself should be density agnostic, in the same way that there is no geography for human rights,” says Negroponte.

Facebook plans to ultimately work with telecommunications companies and satellite operators to roll out the technology Maguire’s team is developing. This year the company should begin flight tests of its solar-powered Aquila drones, which have a 42-meter wingspan, comparable to a Boeing 737 airliner (see “Meet Facebook’s Stratospheric Internet Drone”). Facebook is also working on laser data links to connect drones to each other and to the ground.

Competitor Alphabet, the parent company of Google, is also working on high-altitude drones that could beam down Internet service. Alphabet also has a more mature project aiming to rent flocks of high-altitude “loon balloons” to telecommunications companies to make it economically feasible for them to serve rural areas where cell towers aren’t cost effective (see “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2015: Project Loon”). The first proper trial of that idea is scheduled to take place in Indonesia this year.

This post was updated on February 29, 2016, after Facebook changed the stated resolution of its new maps from 10 to 5 meters.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.