Cybersecurity: The Age of the Megabreach

In November 2014, an especially chilling cyberattack shook the corporate world—something that went far beyond garden-variety theft of credit card numbers from a big-box store. Hackers, having explored the internal servers of Sony Pictures Entertainment, captured internal financial reports, top executives’ embarrassing e-mails, private employee health data, and even unreleased movies and scripts and dumped them on the open Web. The offenders were said by U.S. law enforcement to be working at the behest of the North Korean regime, offended by a farcical movie the company had made in which a TV producer is caught up in a scheme to kill the country’s dictator.

The results showed how profoundly flat-footed this major corporation was. The hack had been going on for months without being detected. Data vital to the company’s business was not encrypted. The standard defensive technologies had not worked against what was presumed to have been a “phishing” attack in which an employee clicked a link that downloaded powerful malware. Taken together, all this showed that many of today’s technologies are not adequate, that attacks can now be more aggressive than ever, and that once breaches occur, they are made worse by slow responses.

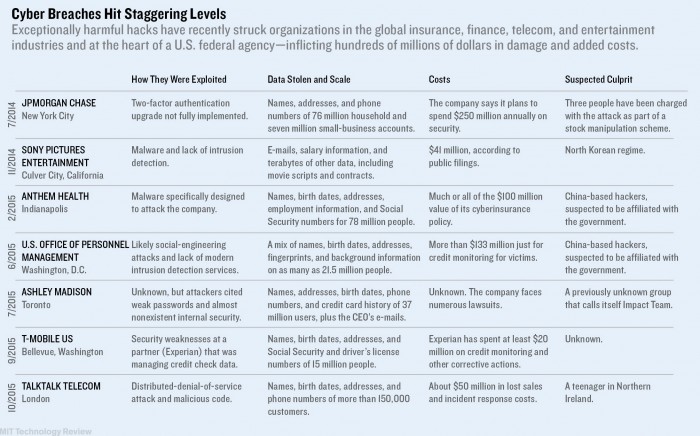

The Sony hack was one in a series of recent data breaches—including many “megabreaches,” in which at least 10 million records are lost—that together reveal the weakness of today’s cybersecurity approaches and the widening implications for the global economy. In 2015, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management was hacked, exposing 21.5 million records, including background checks on millions of people—among them copies of 5.6 million sets of fingerprints. Later in the year, 37 million visitors to Ashley Madison, a dating site for people seeking extramarital affairs, learned that their real e-mail addresses and other data had been released. The theft of data from 83 million customers of Wall Street giant J.P. Morgan, allegedly by an Israel-based team trying to manipulate the stock market, revealed chilling possibilities for how cyberattacks could undermine the financial sector.

Since companies and other organizations can’t stop attacks and are often reliant on fundamentally insecure networks and technologies, the big question for this report is how they can effectively respond to attacks and limit the damage—and adopt smarter defensive strategies in the future. New approaches and new ways of thinking about cybersecurity are beginning to take hold. Organizations are getting better at detecting fraud and other attacks by using algorithms to mine historical information in real time. They are responding far more quickly, using platforms that alert security staff to what is happening and quickly help them take action. And new tools are emerging from a blossoming ecosystem of cybersecurity startups, financed by surging venture capital investment in the area.

But hindering progress everywhere is the general lack of encryption on the devices and messaging systems that hundreds of millions of people now use. Nearly three years ago, when National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden revealed that intelligence agencies were freely availing themselves of data stored by the major Internet companies, many of those companies promised to do more to encrypt data. They started using encryption on their own corporate servers, but most users remain exposed unless they know to install and use third-party apps that encrypt their data.

All these measures will help protect data in today’s relatively insecure networks. But it’s clear that the very basics of how networked technologies are built need to be rethought and security given a central role. A new national cybersecurity strategy is expected to chart an R&D plan to make sure software is verifiably secure and that users know when it’s not working.

There’s a big opportunity: the number of Internet-connected devices—not including smartphones, PCs, and tablets—could reach two billion in just five years. A 2015 McKinsey report predicts that this will become a multitrillion-dollar industry by 2025. All these new devices will present an opportunity to build things robustly from the start—and avoid having them play a role in Sony-like hacks in the future.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Sam Altman says helpful agents are poised to become AI’s killer function

Open AI’s CEO says we won’t need new hardware or lots more training data to get there.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.