In Pursuit of an Affordable Tablet for the Blind

An inexpensive, full-page Braille tablet could make topics like science and math more easily accessible to the blind, according to a team of researchers who have built a prototype device.

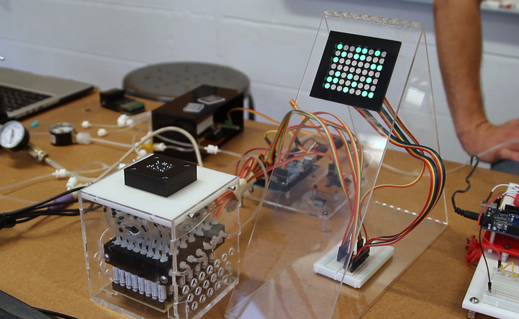

The device, which is under development at the University of Michigan, uses liquid or air to fill tiny bubbles, which then pop up and create the blocks of raised dots that make up Braille. Each bubble has what is essentially a logic gate that opens or remains closed to control the flow of liquid after each command, according to Sile O’Modhrain, a professor of performing arts technology who collaborated on the tablet.

Existing refreshable Braille displays tend to max out at one line of text and cost several thousand dollars. They use plastic pins pushed up and down by a motor. The Michigan team found it impossible to pack the pins in densely enough to create a reasonably sized full-page display, and as a result started from scratch with the microfluidic option. The switch could help them make the final product tablet-sized instead of laptop-sized, like existing refreshable displays.

The tablet borrows manufacturing techniques from the silicon industry, where chips are laid down in layers instead of having many small parts to assemble. As a result, the Michigan team is aiming to offer a Braille tablet for less than $1,000.

“My observation is that, currently, even many of us who read Braille well find reading it with single-line Braille displays slower and more tiring than using text-to-speech or audio materials,” says Chris Danielsen, a spokesperson for the National Federation of the Blind. “I think this would dramatically change with a larger display, especially one at a reasonable price point.”

As access to text-to-speech software has grown, pressure to learn Braille has dropped. A 2009 report from the National Federation of the Blind stated that less than 10 percent of blind children were learning Braille at the time, compared with 50 to 60 percent at Braille’s height in the 1960s.

But that doesn’t mean there is no longer a need for the 200-year-old writing system. Braille books, for example, have long been used to show the blind textured images. Text-to-speech software can’t convey the same visual information. However, if there isn’t a book available, people with visual impairments have to turn to another person to prepare them materials, which can be expensive.

“Anything where you want to be able to see stuff written down, like coding or music or even just mathematics, you really have to work in Braille,” says O’Modhrain, who is visually impaired. “That just means for a lot of people these things are not accessible or not available.”

O’Modhrain believes the team is about a year and a half away from commercializing the technology, which may be used for an application other than Braille at first. That would drive the cost down for its later adoption by the blind.

“It would be great to see these getting into school so children can learn to read math and science materials,” O’Modhrain says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.