Junk-Eating Rocket Engine Could Clear Space Debris

At 16:56 UTC on August 29, 2009, an Iridium communications satellite suddenly fell silent. In the hours that followed, the U.S. Space Surveillance Network reported that it was tracking two large clouds of debris—one from the Iridium and another from a defunct Russian military satellite called Cosmos 2251.

The debris was the result of a high-speed collision, the first time this is known to have happened between orbiting satellites. The impact created over 1,000 fragments greater than 10 centimeters in size and a much larger number of smaller pieces. This debris spread out around the planet in a deadly cloud.

Space debris is a pressing problem for Earth-orbiting spacecraft, and it could get significantly worse. When the density of space debris reaches a certain threshold, analysts predict that the fragmentation caused by collisions will trigger a runaway chain reaction that will fill the skies with ever increasing numbers of fragments. By some estimates that process could already be underway.

An obvious solution is to find a way to remove this debris. One option is to zap the larger pieces with a laser, vaporizing them in parts and causing the leftovers to deorbit. However, smaller pieces of debris cannot be dealt with in this way because they are difficult to locate and track.

Another option is send up a spacecraft capable of mopping up debris with a net or some other capture process. But these missions are severely limited by the amount of fuel they can carry.

Today, Lei Lan and pals from Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, propose a different solution. Their idea is to build an engine that converts space debris into propellant and so can maneuver itself almost indefinitely as it mops up the junk.

Their idea is simple in principle. At a high enough temperature, any element can be turned into a plasma of positive ions and electrons. This can be used as a propellant by accelerating it through an electric field.

The details are complex, however. In particular, the task of turning debris into a usable plasma is not entirely straightforward.

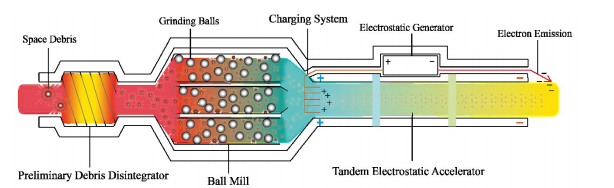

Lei and co focus their efforts on debris that is smaller than 10 centimeters in size, the stuff that laser ablation cannot tackle. Their idea is to capture the debris using a net and then transfer it to a ball mill. This is a rotating cylinder partially filled with abrasion-resistant balls that grind the debris into powder.

This powder is heated and fed into a system that separates positively charged ions from negatively charged electrons. The positive ions then pass into a powerful electric field that accelerates them to high energy, generating thrust as they are expelled as exhaust. The electrons are also expelled to keep the spacecraft electrically neutral.

Of course, the actual thrust this produces depends on the density of debris, the nature of the powder it produces, on the size of the positive ions, and so on. All this is hard to gauge.

And while the spacecraft does not need to carry propellant, it will need a source of power. Just where this will come from isn’t clear. Lei and co say that solar and nuclear power will suffice but do not address the serious concerns that any nuclear-powered spacecraft in Earth orbit will generate.

Nevertheless, the work provides food for thought. Space debris is an issue that looks likely to get significantly worse in the near future. It is an area where new ideas are desperately needed before the next big collision fills Earth’s orbits with even more debris.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1511.07246 : Debris Engine: A Potential Thruster for Space Debris Removal

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.