How the New Science of Game Stories Could Change the Future of Sports

“Serious sport is war minus the shooting.” Many athletes will agree with George Orwell’s famous observation. But many fans might add that the best sport is a form of unscripted storytelling: the dominant one-sided thrashing, the back-and forth struggle, the improbable comeback, and so on.

These storylines play out on sporting fields of all kinds in every corner of the world. But they are just a fraction of all possible stories in the parameter space of sporting endeavor. And that raises an interesting question—what is the nature of this story space and how does it differ from, say, a set of events that are entirely random?

Today, we get an answer thanks to the work of Dilan Patrick Kiley at the Computational Story Lab at the University of Vermont in Burlington and a few pals who have studied the story space of a professional sport for the first time. These guys say their work provides new insight into the narrative appeal of real games and into the nature of sport itself.

The game these guys chose for their study was Australian Rules Football, a game played by two teams of 18 players on a field up to 185 meters long. (By contrast an American football field is 110 meters long.) The ball can be kicked or punched, but not thrown, between players and a key feature of the game is the spectacular catches that players make.

There are four posts at each end of the field that mark the goal area. A team gets 1 point if the ball is kicked or punched through either of the outer two sets of posts and 6 points if the ball passes through the inner set of posts.

On average, teams score about 100 points in a game, each of which take place over four quarters of about 30 minutes each, including stoppage time.

To explore the space of all game stories, these guys downloaded the scoring progressions for more than 1,300 professional Australian rules football games that took place between 2008 and 2014. They then plotted the difference in score for each second of every game.

This creates a “worm” plot that tracks the difference in score and which Kiley and co call the game story. “Each game story provides a rich representation of a game’s flow, and, at a glance, quickly indicates key aspects such as largest lead, number of lead changes, momentum swings, and one-sidedness,” they say.

These game stories have interesting properties. For example, there is slightly more scoring in the second half than the first. And the probability of a team scoring next increases with the size of their lead, a statistical feature that is common to many sports.

Kiley and co took these overall statistical biases and used them to simulate game stories using coin tosses that were biased in the same way. By comparing the real game stories to the simulated ones, they aimed to better understand the nature of real games.

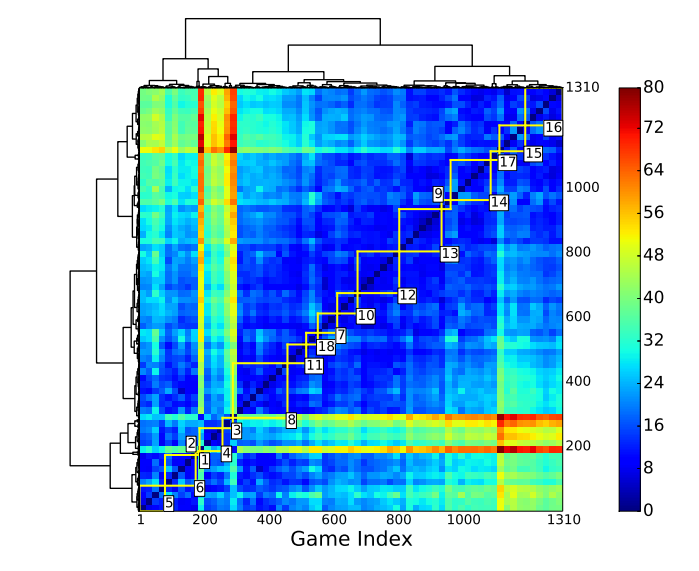

The results make for interesting reading. The team began by looking for clusters of games with similar characteristics. They found that the games covered a huge spectrum of characteristics from blowouts to nail-biters to improbable comebacks. Altogether they found 71 different repeating patterns, or motifs, in this game space.

These motifs fell into seven different categories: one-sided runaway matches; games in which one team was losing early on, came back and then pulled away; Initially even contests with one side eventually breaking away; one team taking an early lead and then holding for the rest of the game; various tight contests; successful comebacks; and finally unsuccessful comebacks.

Curiously, these story lines are not straightforward to simulate, even using the biased coin toss method. Kiley and co say they found much less variety in the simulated games. “We find only 43 motifs for the random model, and these necessarily form a considerably less diverse set than the 71 observed for real AFL games,” they say.

In particular, they found that in random games, one-sided thrashings were far less severe. Curiously, random games also lacked the entire cluster of unsuccessful comebacks.

Just why random games are so different isn’t entirely clear. One idea is that psychological factors conspire to influence the results of real games but are obviously absent in simulated ones and this may be a factor in the differences.

Overall, that’s interesting work that points to a variety of future directions. For example, Kiley and co suggest that a good understanding of the variety of game stories could help people analyze and forecast potential outcomes. “Knowledge of game story shapes could be useful in prediction,” they say.

And they suggest that in future they could study the relationship between game stories and the aesthetic qualities of a game—how much the fans enjoyed the game. “Would true fans rather see a boring blowout with their team on top than witness a close game?” they ask. “To what extent do large momentum swings engage an audience?”

Kiley and co end with an interesting corollary. If fans prefer some game stories over others, why not change the rules in a way that favors the more popular motifs? The team says the results of studies like this may help administrators do exactly this; to make their sport more engaging by changing the rules to promote certain motifs over others.

And this kind of analysis is by no means limited to Australian rules football. Surely it won’t be long before we see similar studies of game story ecologies for American football, baseball, and basketball and other games. George Orwell would have been amazed.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1507.03886 : The Game Story Space of Professional Sports: Australian Rules Football

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.