The Social-Network Illusion That Tricks Your Mind

One of the curious things about social networks is the way that some messages, pictures, or ideas can spread like wildfire while others that seem just as catchy or interesting barely register at all. The content itself cannot be the source of this difference. Instead, there must be some property of the network that changes to allow some ideas to spread but not others.

Today, we get an insight into why this happens thanks to the work of Kristina Lerman and pals at the University of Southern California. These people have discovered an extraordinary illusion associated with social networks which can play tricks on the mind and explain everything from why some ideas become popular quickly to how risky or antisocial behavior can spread so easily.

Network scientists have known about the paradoxical nature of social networks for some time. The most famous example is the friendship paradox: on average your friends will have more friends than you do.

This comes about because the distribution of friends on social networks follows a power law. So while most people will have a small number of friends, a few individuals have huge numbers of friends. And these people skew the average.

Here’s an analogy. If you measure the height of all your male friends. you’ll find that the average is about 170 centimeters. If you are male, on average, your friends will be about the same height as you are. Indeed, the mathematical notion of “average” is a good way to capture the nature of this data.

But imagine that one of your friends was much taller than you—say, one kilometer or 10 kilometers tall. This person would dramatically skew the average, which would make your friends taller than you, on average. In this case, the “average” is a poor way to capture this data set.

Exactly this situation occurs in social networks, and not just for numbers of friends. On average, your coauthors will be cited more often than you, and the people you follow on Twitter will post more frequently than you, and so on.

Now Lerman and co have discovered a related paradox, which they call the majority illusion. This is the phenomenon in which an individual can observe a behavior or attribute in most of his or her friends, even though it is rare in the network as a whole.

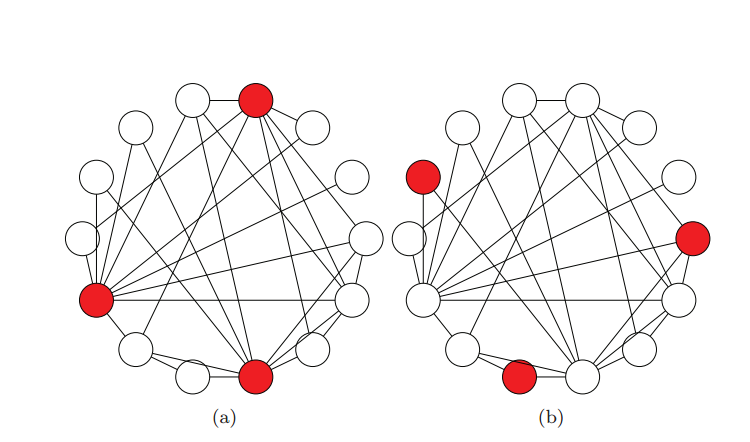

They illustrate this illusion with a theoretical example: a set of 14 nodes linked up to form a small world network, just like a real social network (see picture above). They then color three of these nodes and count how many of the remaining nodes link to them in a single step.

Two versions of this setup are shown above. In the left-hand example, the uncolored nodes see more than half of their neighbors as colored. In the right-hand example, this is not true for any of the uncolored nodes.

But here’s the thing: the structure of the network is the same in both cases. The only thing that changes is the nodes that are colored.

This is the majority illusion—the local impression that a specific attribute is common when the global truth is entirely different.

The reason isn’t hard to see. The majority illusion occurs when the most popular nodes are colored. Because these link to the greatest number of other nodes, they skew the view from the ground, as it were. That’s why this illusion is so closely linked to the friendship paradox.

Lerman and co go on to tweak the parameters of the network, by changing the distribution of links and so on, to see how the majority illusion depends on them. It turns out that the conditions under which the illusion can occur are surprisingly broad.

So how prevalent is it in the real world? To find out, Lerman and co study several real-world networks including the coauthorship network of high-energy physicists, the follower graph of the social-media network Digg, and the network representing links between political blogs.

And the majority illusion can occur in all of them. “The effect is largest in the political blogs network, where as many as 60%–70% of nodes will have a majority active neighbours, even when only 20% of the nodes are active,” they say. In other words, the majority illusion can be used to trick the population into believing something that is not true.

That’s interesting work that immediately explains a number of interesting phenomena. For a start, it shows how some content can spread globally while other similar content does not—the key is to start with a small number of well-connected early adopters fooling the rest of the network into thinking it is common.

That might seem harmless when it comes to memes on Reddit or videos on YouTube. But it can have more insidious effects too. “Under some conditions, even a minority opinion can appear to be extremely popular locally,” say Lerman and co. That might explain how extreme views can sometimes spread so easily.

It might also explain the spread of antisocial behavior. Various studies have shown that teenagers consistently overestimate the amount of alcohol and drugs their friends consume. “If heavy drinkers also happen to be more popular, then people examining their friends’ drinking behavior will conclude that, on average, their friends drink more than they do,” say Lermann and co.

In other words, blame the majority illusion.

That’s important, but it is not yet a marketer’s charter. For that, marketers must first be able to identify the popular nodes that can create the majority illusion for the target audience. These influencerati must then be persuaded to adopt the desired behavior or product.

That’s a goal that any good marketer will already have identified. At least now they know how and why it can work.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1506.03022 : The Majority Illusion in Social Networks

Deep Dive

Policy

Is there anything more fascinating than a hidden world?

Some hidden worlds--whether in space, deep in the ocean, or in the form of waves or microbes--remain stubbornly unseen. Here's how technology is being used to reveal them.

A brief, weird history of brainwashing

L. Ron Hubbard, Operation Midnight Climax, and stochastic terrorism—the race for mind control changed America forever.

What Luddites can teach us about resisting an automated future

Opposing technology isn’t antithetical to progress.

Africa’s push to regulate AI starts now

AI is expanding across the continent and new policies are taking shape. But poor digital infrastructure and regulatory bottlenecks could slow adoption.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.