Climate Change: Why the Tropical Poor Will Suffer Most

In his encyclical on climate change, leaked earlier this week and scheduled to be released on Thursday, Pope Francis remarks that the most severe impacts of climate change will likely fall on those least able to withstand them: the poor.

“Many poor people live in areas particularly affected by phenomena related to heating,” Francis writes, “and their livelihoods strongly depend on natural reserves and so-called ecosystem services, such as agriculture, fisheries, and forestry.” Many of these people also live in the countries near the Equator; it is inhabitants of the tropics who will feel the effects the soonest, and who will suffer the most.

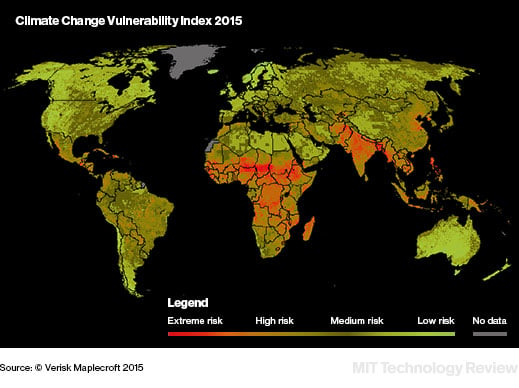

In its annual Climate Change Vulnerability Index, the U.K.-based risk analysis firm Maplecroft lists the top 32 countries at “extreme risk” from climate change. The top 10 are all tropical countries: Bangladesh, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Nigeria, Chad, Haiti, Ethiopia, the Philippines, the Central African Republic, and Eritrea. Of these, all but Nigeria and the Philippines are on the UN’s list of the world’s 48 poorest countries.

The reasons that the poor living at low latitudes will bear the heaviest burdens of climate change are meteorologically, economically, and geopolitically complex, but they all arise from an inescapable statistical fact: normal temperature ranges in the tropics fall within a narrower range than those in more northern climes, and so any deviation is likely to have more significant effects.

“Summers in much of the tropics are already becoming systematically hotter than they used to be, affecting food supplies and contributing to heatstroke and death like we saw in India just this year,” says Susan Solomon, a professor of climate science at MIT.

The tropical effects can be grouped into four areas: natural disasters and drought; public health and disease; political instability and conflict; and economics and agriculture.

Disasters: Every time a major storm hits the United States it sparks anew the debate over whether individual weather events are caused by global warming. There is little doubt among scientists, though, that climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events—and that these events wreak the most damage in the tropics, particularly on coastal cities and island nations like the Philippines. Rising seas make storm surges higher; warming oceans help feed typhoons and tropical cyclones; and increased drought ravages croplands in places like sub-Saharan Africa. Wealthy people in Florida and Hong Kong may see their waterfronts damaged and their real estate values fall; poor people in Bangladesh and the Philippines will see their homes and their livelihoods destroyed.

Disease: Warmer temperatures and wetter months will accelerate the proliferation of tropical diseases, particularly insect-borne ones like malaria, which kills more than 600,000 people a year, almost all of them in the tropics, and dengue. Climate change is likely to increase the frequency and magnitude of weather patterns like El Niño, according to the World Health Organization, increasing mosquito populations and causing epidemics of the diseases they carry. Warmer temperatures will also facilitate the spread of malaria to higher altitude areas like the Debre Zeit region of central Ethiopia, which have been mostly immune to mosquito-spread diseases.

Instability: Dozens of books have been written asking why political instability, despotism, and economic underdevelopment are more prevalent in the tropics than in the temperate zones of Europe, North America, and East Asia. But there is no question that political instability reduces societies’ ability to adapt to changing climate conditions, and that climate change will contribute to unrest and conflict in tropical countries. Poorly governed countries are less able to cope with dramatic environmental shifts, and their citizens suffer as a result.

Agriculture: Simply put, farming is more vulnerable to climate change than almost any other livelihood, because of drought, flooding, crop disease, and other effects. And more people make their living off the land in the tropics than in any other region. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Changehas forecast crop-yield declines of up to 50 percent for developing-world staples such as rice, wheat, and corn over the next 35 years in some areas—most of them in the tropics. Large industrial agriculture operations in developed nations can use irrigation and genetic modification to cope with climate change. Subsistence farmers cannot.

“A world in which the rich will emit while the poor will suffer is not one many people would want,” says Solomon. That is the basic message of the Pope’s letter. Unfortunately, for now, it’s the world we are headed for.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.