Why Robots and Humans Struggled with DARPA’s Challenge

When some of the world’s most advanced rescue robots are foiled by nothing more complex than a doorknob, you get a good sense of the challenge of making our homes and workplaces more automated.

At the DARPA Robotics Challenge, a contest held over the weekend in California, two dozen extremely sophisticated robots did their best to perform a series of tasks on an outdoor course, including turning a valve, climbing some steps, and opening a door (see “A Transformer Wins DARPA’s $2 Million Robotics Challenge”). Although a couple of robots managed to complete the course, others grasped thin air, walked into walls, or simply toppled over as if overcome with the sheer impossibility of it all. At the same time, efforts by human controllers to help the robots through their tasks may offer clues as to how human-machine collaboration could be deployed in various other settings.

“I think this is an opportunity for everybody to see how hard robotics really is,” says Mark Raibert, founder of Boston Dynamics, now owned by Google, which produced an extremely sophisticated humanoid robot called Atlas (see “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2014: Agile Robots”). Several teams involved in the DARPA Robotics Challenge used Atlas robots to participate. Other teams brought robots they had built from scratch.

Above top: The winning robot, DRC-Hubo from South Korea, prepares to turn a valve.

Above bottom: Members of team MIT.

Atlas can balance dynamically, meaning it can walk at a brisk pace or stay balanced on one leg even when given a push. Even so, stability proved difficult for bipedal robots at the DARPA challenge during maneuvers such as walking across sand, striding over piles of rubble, and getting out of a car. Several of the teams using Atlas saw their robots come crashing to the ground during the contest.

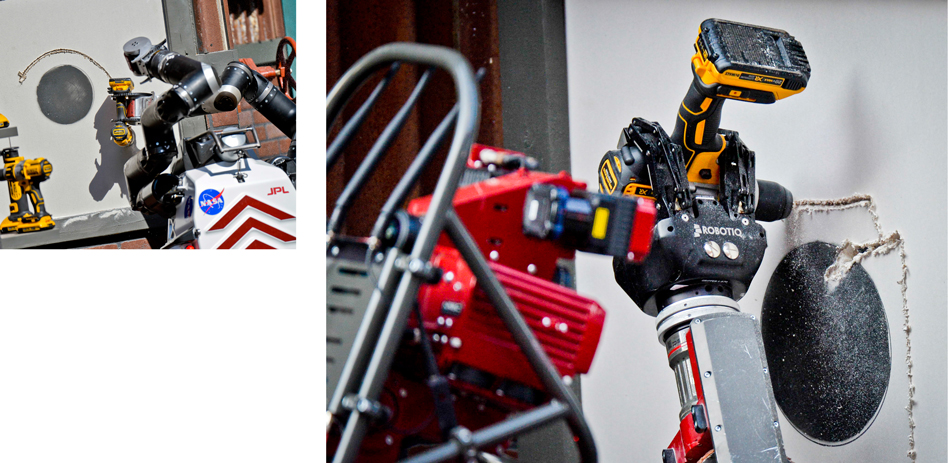

The way many robots struggled to grasp objects and use them properly also highlighted the difficulties in perfecting machine vision and manipulation. Picking up an electric drill and using it to cut a hole in a wall proved especially challenging for most of the robots. T Robot sensors struggle to see shapes accurately in the kind of variable lighting found outside, and robot hands or grippers lack the delicate, compliant touch of human digits.

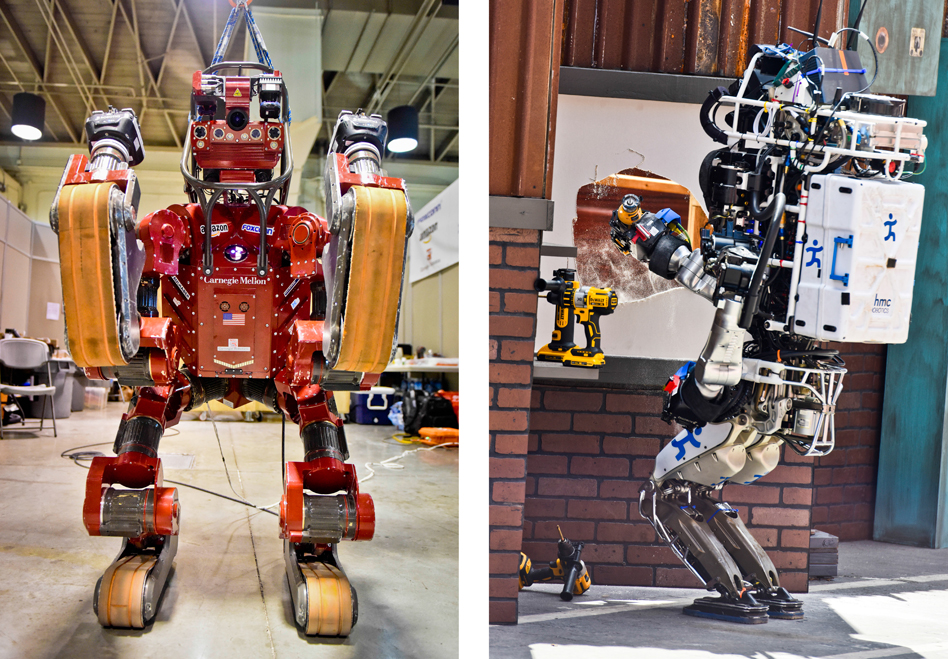

Right: Chimp, a robot from Carnegie Mellon University, does the same.

The robots involved in the event weren’t always acting autonomously (although it was hard for spectators to know when they were). The challenge was designed to simulate the conditions faced by a tele-operated robot entering a nuclear power station, so communications were throttled to simulate radio interference. While this encouraged teams to give their machines some autonomy, it was often possible for a human controller to step in when things went wrong.

The teams involved in the competition used differing levels of autonomy. The team from MIT, for instance, made their Atlas robot, called Helios, capable of acting very autonomously. The team’s human operators could, for instance, point to an area that might contain a lever, and let the robot plan and execute its own course of action. However, they could also take more direct control if necessary.

In contrast, Team Nimbro from the University of Bonn, in Germany, chose more direct control, with nine different people controlling the robot during different tasks (at one point a team member donned an Oculus Rift virtual reality headset and used a gesture-tracking system to control the robot). Team Nimbro finished fourth, with seven out of eight points, while the team from MIT finished seventh, with the same number of points but a slower time.

The teams that performed best in the challenge seemed to have taken a particularly careful approach to blending robot and human abilities. In So Kweon, principle investigator for the sensor system in DRC-Hubo, the winning robot, from KAIST, a research university in Korea, cited human-robot collaboration as key to his team’s success. “These tasks require a good combination of human operation and [the robot’s] recognition and understanding the environment,” Kweon said. “We worked very hard to make a nice balance between those two components.”

Right: IHMC’s robot makes a breakthrough on the wall-drilling challenge.

The team that finished in second place, from the Florida Institute of Human and Machine Cognition, used a sliding scale of automation, allowing a human to assume more decisions and control if its robot seemed stumped, or if a simulation suggested the robot would run into problems by following its own course. Such approaches could become more important as more collaborative robots are introduced in settings such as factories.

The team from Carnegie Mellon University, which finished third, with eight points, followed a similar approach, according to team leader Tony Stentz. “The real advancement here is the robots and the humans working together to do something,” Stentz said. “The robot does what the robot’s good at, and the human does what the human is good at.”

Gill Pratt, the DARPA program manager who organized the Robotics Challenge, said it was important to realize that the level of automation in the competing robots was still quite limited, even if their actions sometimes seemed eerily natural. “These things are incredibly dumb,” he said. “They’re mostly just puppets.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.