Cochlear Implant Also Uses Gene Therapy to Improve Hearing

Researchers have demonstrated a new way to restore lost hearing: with a cochlear implant that helps the auditory nerve regenerate by delivering gene therapy.

The researchers behind the work are investigating whether electrode-triggered gene therapy could improve other machine-body connections—for example, the deep-brain stimulation probes that are used to treat Parkinson’s disease, or retinal prosthetics.

More than 300,000 people worldwide have cochlear implants. The devices are implanted in patients who are profoundly deaf, having lost most or all of the ear’s hair cells, which detect sound waves through mechanical vibrations, and convert those vibrations into electrical signals that are picked up by neurons in the auditory nerve and passed along to the brain. Cochlear implants use up to 22 platinum electrodes to stimulate the auditory nerve; the devices make a tremendous difference for people but they restore only a fraction of normal hearing.

“Cochlear implants are very effective for picking up speech, but they struggle to reproduce pitch, spectral range, and dynamics,” says Gary Housley, a neuroscientist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, who led development of the new implant.

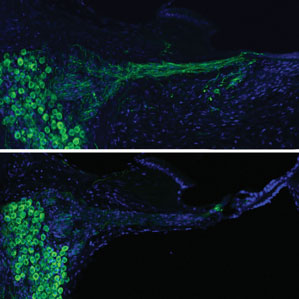

When the ear’s hair cells degrade and die, the associated neurons also degrade and shrink back into the cochlea. So there’s a physical gap between these atrophied neurons and the electrodes in the cochlear implant. Improving the interface between nerves and electrodes should make it possible to use weaker electrical stimulation, opening up the possibility of stimulating multiple parts of the auditory nerve at once, using more electrodes, and improving the overall quality of sound.

Peptides called neurotrophins can encourage regeneration of the neurons in the auditory nerve. Housley used a common process, called electroporation, to cause pores to open up in cells, allowing DNA to get inside. It usually requires high voltages, and it hasn’t found much clinical use, but Housley wanted to see whether the small, distributed electrodes of the cochlear implant could be used to achieve the effect.

Housley’s group used deafened guinea pigs, which are commonly used as a hearing model because their cochleas are similar in size to those found in humans. During surgery to place the cochlear implant, they injected the cochlea with a neurotrophin gene vector. Once the implant was placed, they applied an electroporation voltage using the electrodes. The process, which took only a few seconds during surgery, resulted in nerve regeneration in the animals. And weeks after implantation, the nerves of treated animals showed stronger responses to signals from the implant, which suggests they are able to hear more. This research is described this week in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

“Clearly this works—in a guinea pig,” says Lawrence Lustig, director of the Cochlear Implant Center at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. Lustig’s group and others have been exploring gene therapy, but they use a virus to deliver the neurotrophin gene.

Robert Shepherd, director of the Bionics Institute, a nonprofit medical research center in Melbourne, Australia, says electrode-directed gene therapy could improve other kinds of neural interfaces. “Wherever we’re applying electrodes, whether it’s for deep-brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease, or retinal implants for the blind, there is already neural damage,” he says.

Housley’s group is working with Cochlear, a major maker of cochlear implants headquartered in Sydney, to test the electrode and gene-therapy combination in a clinical trial.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.