How To Track Vehicles Using Speed Data Alone

Location is a key indicator of personal travel patterns and habits. Numerous studies of location-based data sets show that they can be used to reveal huge amounts of information about people’s routines, commutes, workplaces and other activities. Consequently, there is growing concern that location data must be treated with considerable care.

An increasing number of car insurance companies have begun to take note. One way these companies reduce the cost of insurance is by gathering data about their driving practices.

And to preserve the privacy of their customers, many insurance companies do not collect location data but only time-stamped driving speeds instead. The idea is that the speed and accelerations that occur when you drive give a good indication of your driving technique but without revealing your routes.

Today, Janne Lindqvist, Bernhard Firner and pals at Rutgers University in New Jersey say that this method may not be as privacy preserving as first thought. Indeed, these guys have created an algorithm that can predict the final location of a journey given only the starting point and the time-stamped driving speeds. “We show that with knowledge of the user’s home location, as the insurance companies have, speed data is sufficient to discover driving routes and destinations when trip data is collected over a period of weeks,” they say.

The problem of determining a route given only the speed of the car is a hard one to solve. Given some starting point, the number of possible routes increases dramatically the further the car travels. Certain patterns of speed changes can help trim the number of possibilities. For example, a car must come to a stop at certain junctions and can only turn left or right when its speed is below some threshold value.

By matching these patterns of speed changes to the topology of the road, it ought to be possible to determine the route the vehicle has taken.

In practice, this is a tricky business. A vehicle may stop at the junction but also because of numerous other reasons such as road works or other hold ups. A car has to slow down to make a left or right turn but may also slow down in the same way when the car in front turns instead.

Then there are uncertainties over the distance traveled. This varies according to driving techniques and the condition of the road, which might require a driver to steer around potholes, for example

The problem for any algorithm is the sheer number of possible routes that might be taken. The algorithm must compare different possible routes, evaluate them and choose the one that rates most highly. But this only works if the data is good enough to identify the route accurately. And therein lies the problem.

Given these uncertainties, it’s easy to assume that the vehicle speed data by itself gives little if any indication of the route taken. However, Lindqvist, Firner and co prove otherwise.

These guys have developed an algorithm known that can recreate a vehicle’s driving path given its time-stamped speed data and its starting location. Their approach is based on the idea that matching the speed data to a specific path requires the distance moved to be stretched or compressed. “For instance, if the speed data goes to 0 indicating a stop where there is no intersection we might pull the path forward by some distance to reach an intersection,” they say.

When the algorithm does this, it “pins” the earlier route which cannot then be changed. That allows it to focus only on the routes that are possible after the intersection at which it was pinned. “We call this approach elastic pathing because of the stretching and compressing of the speed trace to fit the road is conceptually similar to stretching a piece of elastic along a path while pinning it into place at different points,” they explain.

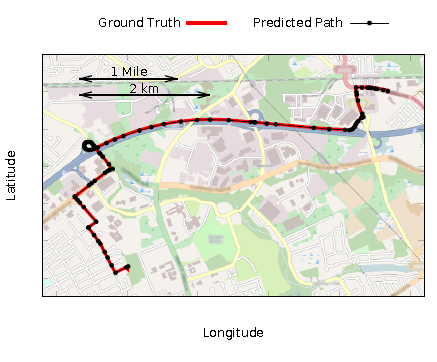

To test the algorithm, Lindqvist, Firner and co measured the speed characteristics of seven drivers travelling from their homes to 46 unique destinations over 240 journeys. At the same time, they also measured the location of the cars using a GPS device to give ground truth data.

The results are revealing. Lindqvist, Firner and co say they were able to predict the final destination to within 500 metres for 20 percent of the journeys. “This means that a location visited daily can be identified in about a week; locations visited on a weekly basis could be identified with slightly more than a month of data,” they say.

Even when it is not possible to identify the destination, the algorithm nevertheless rules out a large portion of possible destinations. What’s more, it also identifies variations in daily routines without needing to know anything about the final endpoint.

That’s somewhat different from the claim that speed data gives no information about a vehicle’s route or destination, as some insurance companies have claimed.

Location data can be used to gain all kinds of insights into a person’s behaviour, social activities and work activities. Lindqvist, Firner and co suggest that an interested party could get answers to questions such as: Did you go to an anti-war rally on Tuesday?”, “Did you see an AIDS counselor?”, “Have you been checking into a motel at lunchtimes?”, “Why was your secretary with you?”, or “Which church do you attend? Which mosque? Which gay bars?”

Lindqvist, Firner and co point out that even if insurance companies do not use speed data in this way now, there is no guarantee that they won’t use it like that in future, or that some other organisation might not mine the data in this way in future. Indeed, part of the problem is that speed data is not considered private and so may be made available in ways that private data can never be.

These guys end by saying that there are various alternatives to speed data that give a good indication of driving habits but offer a much better privacy protection. For example, some insurance companies simply gather mileage data or minutes of use.

Something to think about next time you opt for a usage-based insurance policy.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1401.0052: Elastic Pathing: Your Speed is Enough to Track You

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.