New IPCC Report Strengthens Certainty of Climate Change

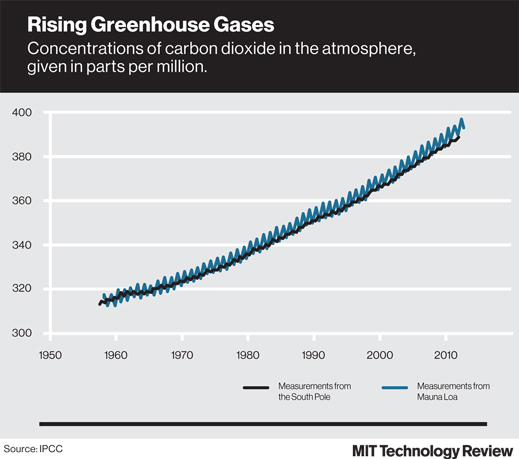

The latest report from the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that scientists are more certain than ever that humans are causing global warming, and that climate change will get worse if greenhouse gas levels continue to rise.

The report is influential with policymakers because it represents the consensus of hundreds of scientists who have worked for years to draw conclusions from the scientific research on climate change.

The report, the first of four IPCC reports scheduled for this year, focuses on the science of climate change. The other reports will take a closer look at the likely impacts of climate change and what can be done to minimize them.

While there are some changes compared to the IPCC’s previous report, which was released in 2007, the new report is notably similar. It acknowledges that over the last 15 years temperatures haven’t risen as fast as they had been in the preceding years. But while this fact has been fodder for climate change skeptics, the report says that the slowdown is part of the climate’s natural variability, not evidence that long-term climate change isn’t happening. The report’s predictions of temperature increases are largely in line with the last report.

“Climate science is a well-established science with a history that goes back more than 150 years,” says Ken Caldeira, a professor in the Department of Environmental Earth System Sciences at Stanford University. “For a mature science such as climate science, I don’t believe that there are individual results that dramatically change what the science is saying. Nor do the basic findings of such a mature science change very much in just a few years.”

Mostly, the changes in the new report are a matter of emphasis. For example, the 2007 summary for policymakers didn’t talk about geoengineering—a range of technologies meant to cool the planet by, for example, injecting particles into the upper atmosphere to reflect sunlight back into space. Since that report was published, geoengineering has gained more attention as a potential way to address climate change, so the new summary notes that much uncertainty remains around the potential effects of geoengineering schemes (see “The Geoengineering Gambit” and “A Cheap and Easy Plan to Stop Global Warming”).

What’s most striking are not the projections for the future—which depend heavily on assumptions about things like how much carbon dioxide will be emitted—but rather what the report says about what is happening now. Ice is melting faster; the ocean is becoming more acidic; and weather patterns are changing, the report says.

“One of the important conclusions of this report that will resonate with a lot of people is the evidence for an increased frequency of heat waves in many parts of the world,” says Susan Solomon, a professor of atmospheric chemistry and climate science at MIT. “Not all types of extreme events are increasing because of climate change, but there is a widespread increase in heat waves that affects both people and ecosystems.”

And in spite of efforts to roll out solar panels and more efficient cars, the reports notes that carbon dioxide emissions continue to increase year after year. In 2011, humans emitted 9.5 gigatons of carbon, up 54 percent over the 1990 level.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.