Implanted Device Controls Rheumatoid Arthritis

In early human tests, SetPoint Medical has found that an electronic implant helped reduce the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis in six of eight patients. The company, which is based in Valencia, California, is one of many groups exploring the potential of electronic implants to treat diseases by delivering pulses to nerves that regulate organ or body functions.

Earlier this month, pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, medical-device manufacturer Boston Scientific, and others invested $27 million in SetPoint. Although nerve-stimulating devices have been available for many years, GSK and academic researchers argue that the field of bioelectronic therapies is just beginning to ramp up and that in the future many conditions could be treated with electrical impulses.

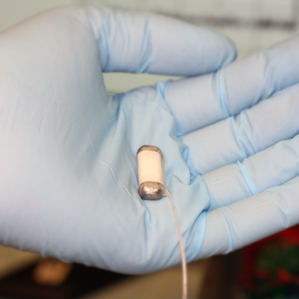

The arthritis-regulating device is implanted in the patient’s neck and wraps around the vagus nerve, a bundle of nerve fibers that communicates sensory information from internal organs and controls involuntary body functions such as heart rate and digestion. The device stimulates the nerve at regular intervals in a particular pattern that regulates the immune system, which is overactive in rheumatoid arthritis.

Brain implants have previously been used to treat movement disorders and some psychiatric conditions (see “Brain Implants Can Rest Misfiring Circuits”). Devices are also used to stimulate nerves outside the brain. An electrical device that stimulates the vagus nerve is already used to treat some cases of drug-resistant epilepsy and depression, and another is undergoing testing as a treatment for congestive heart failure. But SetPoint is covering new ground by testing peripheral-nerve stimulation as a treatment for immune disease.

“The industry is expanding rapidly,” says Kenneth Gustafson, a biomedical engineer at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, who is studying electrical nerve stimulation as a way to treat bladder dysfunction. The precedent set by pacemakers, deep brain implants, and other such devices enables researchers to “take that existing technology and repurpose it for all these new applications,” he says.

Researchers say the main advantage of the electrical devices over drug treatments is that they may not cause as many side effects. “Electrostimulation can be much more selective,” Gustafson says. “The targets are neural circuits that are not behaving as they should.” Drugs, on the other hand, often affect many pathways in the body.

SetPoint has been running animal and human trials using devices developed by another company to treat epilepsy. In the future, trials will use a proprietary device that is smaller and specifically engineered for the infrequent stimulation needed to treat rheumatoid arthritis. The company will soon launch another small patient study to test stimulation in patients with Crohn’s disease, an autoimmune condition that attacks the gastrointestinal system.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.