Six Percent of Free Android Apps Hide Intrusive Adware

As mobile computers have become more common, criminals have begun to explore ways to profit from exploiting them (see “Clues Malware Moving from PC to Phones”). However, figures released today by mobile security company Lookout indicate that people are more likely to fall victim to what it calls “adware” than classic criminal malware.

Lookout sampled 200,000 apps to conclude that 6.5 percent of all free apps in the store for Android devices meet the company’s definition of adware, broadly defined as any app that pushes ads on a user outside of its own interface without consent. Adware might use notifications or add icons to the device homescreen.

When a person in the U.S. installs Lookout onto their Android phone, there is a 0.9 percent chance they already have adware installed, says Jeremy Linden, a security product manager at Lookout. Linden says that suggests more than one million Android device owners in the U.S. downloaded adware in the past year. The chance a user will install adware far exceeds the combined risk of their installing malware that will spend their money, spy on them, or steal data, Lookout’s figures say. “It’s higher than any other app-based threat,” says Linden.

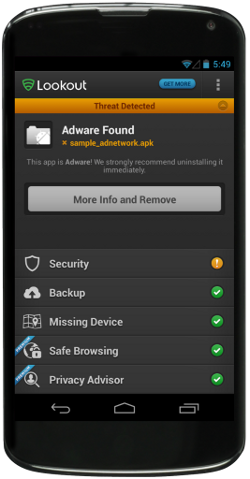

Today, Lookout will begin warning Android owners amongst its 40 million-person userbase when they install an app that meets its definition of adware, something of a shift for a company that, up to now, has focused more on the malware that has long been the core obsession of the security industry.

“Our goal is eradicate the worst of the unscrupulous advertising practices out there,” Linden told MIT Technology Review, adding that his company does not have a problem with ad-supported apps in general. “The small minority of ad networks that behave badly is making a lack of trust for the entire industry,” he says.

Lookout defines adware as an app that without consent shows ads outside its own user interface; collects unnecessary personal data, such as email address or phone number; or leads to SMS messages or phone calls.

Many mobile app makers rely on third-party companies to provide ad technology for their apps. Linden says that Lookout identified “between 5 and 10” mobile ad companies whose technology made apps act like adware and advised them in advance that Lookout was to begin encouraging people to uninstall apps with their technology included. Some changed their practices, says Linden, but five did not. Those companies are LeadBolt, Moolah Media, RevMob, SellARing, SendDroid. Those contacted for comment did not respond by the time this post was published.

Linden says that Lookout believes the ad industry should agree on a set of standard practices for mobile ads and offers its own guidelines as a starting point. The Digital Advertising Alliance, an industry group, is already working on mobile privacy guidelines for its members, but didn’t respond to a request for comment on Lookout’s new effort to warn users of what it thinks are unacceptable advertising tactics.

Lookout isn’t yet introducing similar oversight of ad-supported apps on Apple devices. However, a study presented this week by researchers at University of California, San Diego suggests it is needed (see “Many iPhone Apps Defy Apple Privacy Advice”).

That research was enabled by an app called ProtectMyPrivacy that allows people to selectively choose what data apps can access. Crowdsourced recommendations of what to allow and block for specific apps make using the app easy, but it only works on “jailbroken” Apple devices modified to remove Apple’s restrictions on apps examining one another’s behavior. A request to distribute a version through Apple’s app store that simply told people what ProtectMyPrivacy had uncovered was blocked by Apple. You can find that data on ProtectMyPrivacy’s website instead.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.