Researchers Peek at the Structure of the Viral Internet

A video or article or meme “going viral” is one of the most overused terms on the Internet. The term “virality” is taken from the field of epidemiology, where scientists using computer models attempt to map the spread of a disease. On the Internet, however, we have viral marketers. These are folks who can talk a good game— they even have mathematical equations with borrowed ideas like the virality coefficient—but very little in the way to measure these in a rigorous way. Mostly, we resort to saying something has gone viral simply if it gets a lot of views on YouTube, is trending on Twitter, or spawns a mutated meme. And, of course, if your friends already know about it when you bring it up. Oh, THAT, video.

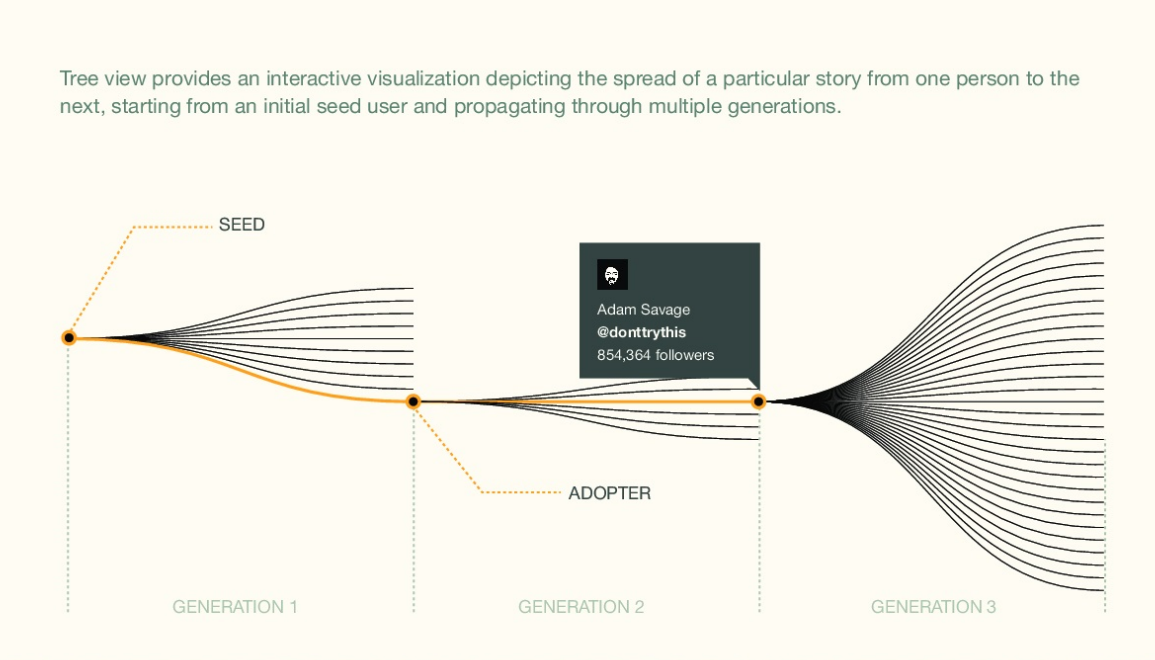

At Microsoft Research’s annual technology demo day this week, researchers showed off a tool called Viral Search that attempts to measure virality in its more literal sense. That means not overall traffic over time, but the mechanics by which it passes from person to person over many generations.

The software looked at 1.4 billion Tweets over the course of a year and produced a branching tree that shows how links spread, based on who follows whom and the sequence of retweets. From this, researcher Jake Hofman and a team created a new kind of Web metric that measures the average distance on the tree between any two people who tweeted the story. More distance means more virality, since there were more paths by which people passed on a link. Something can be relatively “viral,” like an online petition that people sign and often pass on, without getting near Gangham Style levels of hits. The opposite of virality might be a random tweet from Justin Bieber that got a lot of initial hits because he’s Justin Bieber, who has 35 million followers, but died off pretty quickly, because how many other people really care what he’s doing on his family vacation. Most story trees on Twitter were pretty small, with fewer than two “generations” before they died out, the analysis found.

The researchers have packaged these large computations into a neat search and visualization tool, and the conclusion that true virality is rare isn’t astonishing or new. But what’s most interesting were these ideas under the hood. In epidemiology, tracing a germ from person to person so finely is usually not possible. On Twitter it is. That’s the biggest weakness, however. Since Twitter is a social network that is meant to be public, there aren’t actually many other parts of even the Internet world where doing something like this would be possible at any meaningful scale, Hofman says. You can watch a video of the demo here.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.